Every fall, new stenography students line up behind their machines like rookies at training camp. The first takes come fast and brutal. Fingers stumble. Minds freeze. Words vanish mid-sentence.

And just like the first week of an NBA camp, failure happens — publicly, repeatedly, painfully.

But here’s the hidden truth behind every elite performer, whether on the court or in a courtroom: the most successful aren’t the most talented. They’re the most mentally conditioned.

The Athlete’s Cycle: Fail → Reflect → Adjust → Repeat

When an NBA rookie misses a layup, the coach doesn’t just yell. He rewinds the film.

They study the angle, the timing, the hesitation. Then they run the drill again — slower, smarter, focused on the fix.

That’s what elite performers do. They analyze the failure while it’s still warm.

Every top court reporter has gone through the same cycle:

- Drop a word.

- Replay the stroke.

- Identify the hesitation.

- Drill the fix.

Each misstroke is just data — not a verdict.

That’s what makes professional reporters mentally bulletproof. They’ve trained their brains to separate mistake from identity. They don’t crumble when something goes wrong in court; they adjust mid-sentence.

You can train that same mental muscle — but only if you treat steno practice like athletic conditioning.

Film Study for Stenographers

Athletes watch game tape. Stenographers have translation logs.

After every dictation, open your software and look for the patterns:

- What words mis-translated repeatedly?

- Which briefs caused hesitation?

- Where did accuracy drop when speed increased?

That’s your film review. It’s not punishment — it’s pattern recognition.

Don’t just look at how many errors you made; look at what kind.

Was it a hesitation? A wrong brief? A mental freeze?

Each category reveals a different skill gap.

The more precisely you diagnose it, the faster you close it.

Athletes don’t just run laps to get better — they train the exact muscles that failed.

You should too.

Pressure Reps – Your Mock Trials Are Game Day

You can’t become a pro by only practicing alone.

NBA players don’t just shoot in empty gyms. They scrimmage. They simulate crowd noise, adrenaline, and unpredictability.

For you, that means mock trials, live dictations, group readbacks, realtime labs.

Those are your scrimmages.

The goal isn’t perfection — it’s composure. You’re teaching your nervous system to stay calm when your adrenaline spikes.

Every time your instructor says, “Ready? Begin,” that’s your tip-off.

Every time you recover from a dropped word and keep going, that’s your clutch shot.

When you train under pressure, you’re building the exact resilience you’ll need when a witness starts mumbling at 300 wpm on the record.

The Mental Recovery Game

What separates a great athlete from a burnt-out one isn’t just their training load — it’s their recovery routine.

Your mind is a muscle too. It needs cooldowns.

After every intense practice:

- Step away from your machine.

- Take three deep breaths.

- Write down one specific win and one micro-fix for next time.

That reflection — five minutes, tops — is where growth actually happens.

Without it, you just stack fatigue on frustration.

With it, you convert stress into strategy.

The best students don’t practice more; they process better.

Building a Steno Journal – Your Mental Gym Log

Every athlete logs their progress — weights lifted, times improved, reps completed.

You should too.

Create a “Steno Conditioning Journal” with five prompts after every session:

- Speed / Dictation: (e.g., “180 Jury Charge”)

- What challenged me most:

- What I learned:

- Micro-fix for next time:

- Proof of progress: (accuracy %, shorter recovery, better control)

That’s your mental gym log.

You’re not writing a diary — you’re recording data.

And over time, data becomes confidence.

When you flip back through 30 days of entries and see tangible improvement, your brain internalizes a new belief:

“I can do hard things. I’ve done it before.”

That’s the seed of unshakable confidence — built not on praise, but on proof.

Coaching, Not Comfort

When a rookie gets benched after missing shots, the coach doesn’t say, “You’re amazing no matter what.”

He says, “Here’s the tape. Let’s fix your form.”

That’s love, disguised as accountability.

Your instructors are your coaches. Their job isn’t to comfort you; it’s to prepare you.

They push you because they see the future version of you who can take testimony with grace under fire.

So the next time your teacher critiques your work or asks you to redo a take, don’t take it personally. Take it professionally.

That’s how champions are made.

The Mind-Body Connection in Writing Speed

Professional athletes visualize movements before they happen.

A basketball player imagines the arc of a free throw.

A court reporter can do the same with words.

Before each take, close your eyes for 15 seconds.

Picture the rhythm of your fingers, the sound of clean strokes, the steady breathing.

You’re not just typing — you’re synchronizing mind and body.

And when speed builds, your goal isn’t to push harder; it’s to stay looser.

Tension kills both accuracy and endurance.

Flow comes from rhythm, not rigidity.

Think of every dictation like a quarter in a game: focus, breathe, reset.

The Clutch Mindset

In the final seconds of a tied game, the best players don’t think — they trust their training.

That’s what you’re building toward.

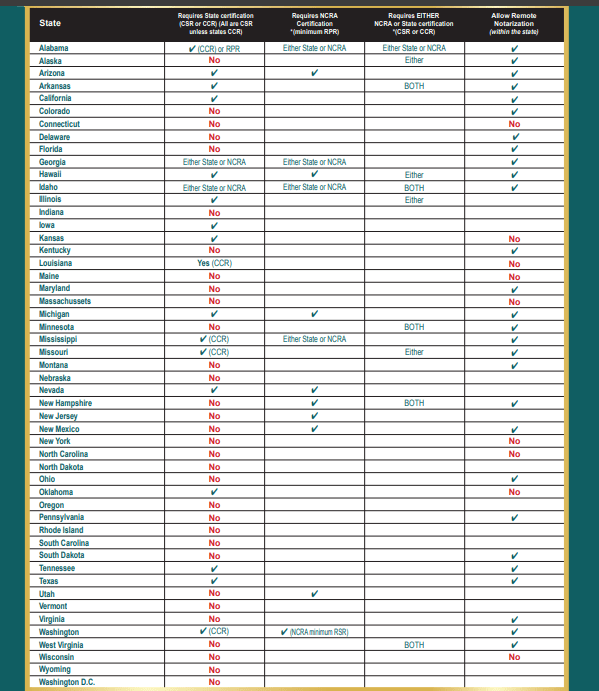

The day you walk into your CSR exam or your first live courtroom job, your nerves will spike.

That’s not fear — that’s readiness.

You’ll have thousands of “reps” behind you: hours of practice, logged reflections, failures studied and overcome.

Your body knows what to do. Your mind just needs to get out of the way.

That’s the clutch mindset — the ability to perform under pressure because you’ve already failed, analyzed, and rebuilt yourself a hundred times before.

The Power of Routine

Great athletes don’t wake up and “see how they feel.” They have systems.

You should too:

- Warm-up: five minutes of finger drills or briefs.

- Core practice: timed takes in varied speeds and voices.

- Cool-down: journaling your reflection and setting your micro-fix.

Consistency beats intensity.

It’s better to do 45 minutes daily than five hours once a week.

Your brain learns through repetition, not marathon sessions.

And discipline doesn’t kill creativity — it frees it.

Proof Over Praise

In steno school, you’ll get plenty of encouragement — “You’ve got this!” “You’re so close!” — and it feels good.

But encouragement alone doesn’t create mastery.

Proof does.

Every entry in your steno journal is proof.

Every line of clean notes is proof.

Every recovered error is proof.

Praise fades. Proof compounds.

When you base your confidence on evidence instead of emotion, no failure can take it away.

The Professional Mindset

Here’s the ultimate truth:

You’re not training to pass a test.

You’re training to walk into a courtroom as the one person everyone depends on.

When the judge speaks, the attorneys argue, and the witness mumbles, you’re the calm in the chaos — the athlete who performs under pressure because they’ve been here before.

That’s what mental conditioning builds.

That’s what daily reflection forges.

Your stenography machine is your instrument, your gym, your arena.

And every word you capture cleanly is a quiet victory — a point on the scoreboard of your own professional growth.

The Challenge: 30 Days of Athletic Mindset

For the next month, treat your practice like training camp.

- Document every take.

- Analyze one pattern daily.

- Write down one micro-fix.

- Track your proof.

By day 30, you won’t just write faster.

You’ll think clearer, recover quicker, and carry yourself like a professional reporter in training — not a student hoping to pass.

Because you’re not “just learning steno.”

You’re building the mental discipline of an elite performer.

And once your brain learns to see every dropped word as data — not defeat — you’ve already joined the big leagues.

StenoImperium

Court Reporting. Unfiltered. Unafraid.

Disclaimer

“This article includes analysis and commentary based on observed events, public records, and legal statutes.”

The content of this post is intended for informational and discussion purposes only. All opinions expressed herein are those of the author and are based on publicly available information, industry standards, and good-faith concerns about nonprofit governance and professional ethics. No part of this article is intended to defame, accuse, or misrepresent any individual or organization. Readers are encouraged to verify facts independently and to engage constructively in dialogue about leadership, transparency, and accountability in the court reporting profession.

- The content on this blog represents the personal opinions, observations, and commentary of the author. It is intended for editorial and journalistic purposes and is protected under the First Amendment of the United States Constitution.

- Nothing here constitutes legal advice. Readers are encouraged to review the facts and form independent conclusions.

***To unsubscribe, just smash that UNSUBSCRIBE button below — yes, the one that’s universally glued to the bottom of every newsletter ever created. It’s basically the “Exit” sign of the email world. You can’t miss it. It looks like this (brace yourself for the excitement):

You must be logged in to post a comment.