Court reporters are trained to hear everything. We’re the quiet observers, the last line of record integrity in every courtroom, deposition, and hearing. But what we’re not trained to hear—until it’s too late—is the sound of our own exhaustion echoing back at us.

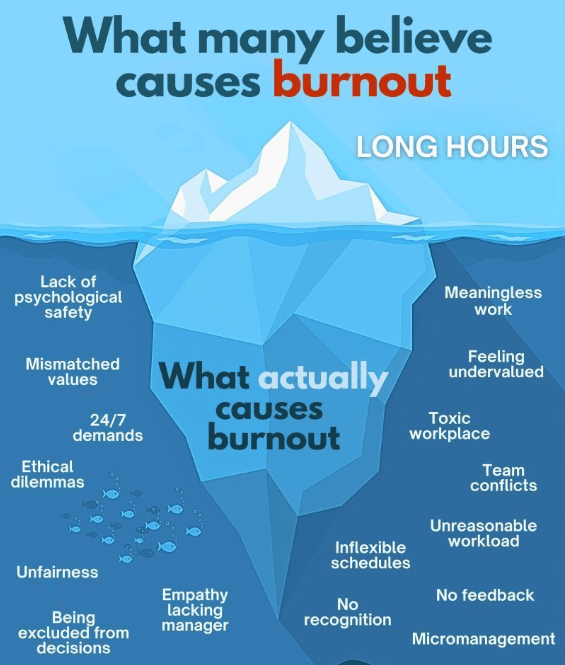

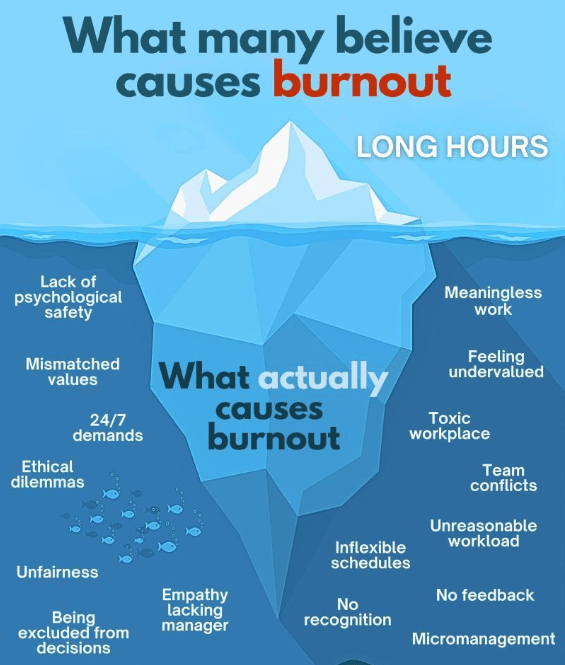

Most people think burnout happens when you work too many hours. In the world of stenography, that assumption almost sounds laughable—of course we work long hours. But that’s not the real danger. The truth is, burnout in court reporting has far less to do with the number of hours we work and far more to do with how those hours feel.

When the work environment becomes toxic, dismissive, or ethically compromising, even a “light day” can feel crushing. You can love the craft of capturing words, yet still feel like you’re drowning under invisible weight.

1. Burnout Isn’t About Hours — It’s About Meaning

Long days on trial or back-to-back depos don’t automatically cause burnout. In fact, many reporters thrive on high-stakes, high-speed work. What drains the soul isn’t the speed of the job—it’s the lack of support and recognition surrounding it.

If you’re spending twelve hours producing real-time feeds, facing impossible turnaround expectations, or being treated like a machine instead of a human, that’s when the cracks begin to form. Burnout isn’t caused by doing too much; it’s caused by feeling like what you do doesn’t matter—or worse, isn’t safe to do with integrity.

When a reporter is pressured to cover a proceeding without a scopist, pushed to accept unethical working conditions, or shamed for asking for payment terms that comply with California’s 30-day rule (SB 988), it chips away at psychological safety. Over time, that invisible stress corrodes motivation faster than any long day could.

2. What You See Isn’t the Whole Iceberg

The visible signs—fatigue, irritability, missed deadlines—are just the tip of the iceberg. Beneath the surface lie the deeper, systemic issues that actually drive burnout.

In our industry, those hidden forces include mismatched values, ethical dilemmas, unfair pay structures, exclusion from decision-making, and a chronic lack of empathy from management.

Reporters who care deeply about the accuracy of the record often find themselves working in environments that don’t value that care. When digital recording firms market “AI transcripts” while paying reporters less for proofreading the machine’s mistakes, it’s not just bad business—it’s emotional sabotage.

Each time a reporter’s professional judgment is ignored, each time quality is sacrificed for cost savings, another piece of trust is lost. And trust, once gone, is nearly impossible to restore.

3. Recognition, Trust, and Inclusion Are Not Perks—They’re Protection

Most agency owners and firm managers underestimate how powerful recognition can be. A simple “thank you” for a late-night expedite or a call to ask how a reporter is holding up can mean the difference between retention and resignation.

But the opposite—silence—communicates something too: You’re invisible.

Invisibility breeds burnout. When reporters feel unseen, undervalued, or excluded from discussions that directly affect their work (like rate setting or scheduling policy), disengagement takes root. It’s not dramatic—it’s gradual. The energy once used to advocate for excellence turns inward into resentment, fatigue, and finally, apathy.

Recognition isn’t a luxury. It’s a psychological safety mechanism. It tells people their work matters, that their voice counts, and that their standards are shared. Without it, every reporter eventually hits the wall—no matter how strong or experienced they are.

4. Micromanagement Is Burnout in Disguise

Micromanagement is the silent killer of motivation. For court reporters, it often shows up as intrusive oversight: constant messages during proceedings, arbitrary style-sheet demands, or mistrust disguised as “quality control.”

When management dictates every comma and expects instantaneous replies to emails at midnight, it destroys autonomy—the single most important driver of satisfaction for skilled professionals.

The irony? The best reporters are self-driven perfectionists. They don’t need to be controlled—they need to be trusted. Micromanagement tells them the opposite: that they’re not competent enough to own their process.

Over time, that erodes confidence and creativity. Reporters stop innovating, stop caring, stop mentoring others. The very excellence firms rely on begins to wither.

5. Ethical Dilemmas: The Hidden Cost of “Just Getting It Done”

There’s another layer unique to our profession: ethical fatigue.

Every time a reporter is asked to “just take the job” without proper notice, to sign an incomplete transcript for a digital recording, or to certify a record they didn’t control, they face a micro-ethical crisis. Those compromises pile up.

Burnout here isn’t just physical—it’s moral. When the system expects you to cut corners, it breeds a constant, gnawing dissonance between your standards and your survival. That’s why so many veteran reporters describe not exhaustion, but heartbreak.

6. Toxic Workplaces and the Erosion of Trust

Toxicity doesn’t always look like shouting matches or public humiliation. Sometimes it’s subtler: favoritism in job assignments, withheld payments, gossiping among staff, or leadership that ignores concerns about scheduling overloads.

When communication breaks down, mistrust blooms. And in a profession that depends on precision, mistrust is lethal. You can’t maintain excellence when you’re constantly on alert for the next unfair decision.

Healthy culture begins where transparency begins. A toxic one thrives on silence.

7. Rebuilding Resilience: What Firms and Reporters Can Do

To prevent burnout, the entire reporting ecosystem—agencies, freelancers, scopists, and attorneys—has to shift perspective.

Here’s what that looks like in practice:

- Promote psychological safety. Encourage honest conversations without retaliation. When a reporter flags an ethical concern or workload issue, it’s not complaining—it’s safeguarding quality.

- Align values. Make sure agency practices match the profession’s ethical code. If profit comes at the expense of integrity, the burnout rate will skyrocket.

- Build flexibility. Rigid schedules are a relic of the past. Allow hybrid work models, flexible transcript deadlines where possible, and mental-health recovery time after long trials.

- Acknowledge and reward. Publicly recognize outstanding work, fairness, and consistency. Appreciation doesn’t cost money—but burnout does.

- Train empathetic managers. Supervisors who understand the emotional intensity of reporting can prevent more attrition than any HR policy ever could.

8. The System Isn’t Broken Because of You—It’s Broken Around You

Burnout makes you feel defective, like you’ve lost your edge or your stamina. But most reporters aren’t broken—the system is.

We’re operating in a profession where workload demands have risen exponentially, legal expectations have multiplied, and yet recognition and compensation have not kept pace. Add the rise of undertrained digital reporters, AI encroachment, and post-pandemic workforce isolation, and it’s no wonder burnout rates are quietly soaring.

It’s time for the industry to look beneath the surface. Long hours may be the visible iceberg tip, but the real causes—lack of trust, empathy, fairness, and inclusion—are what sink careers.

9. A Call to the Profession

If we want to keep the next generation of stenographers inspired, we must repair the ecosystem they’re inheriting. That means protecting psychological safety, prioritizing ethics over expedience, and treating reporters as partners, not vendors.

Burnout doesn’t just empty chairs; it empties the profession of its soul.

Court reporters are the historians of truth. But to keep writing history, we have to make sure we don’t disappear beneath the surface ourselves.

Have you experienced burnout as a court reporter? What helped you recover—or what warning signs did you miss? Share your story. Someone else may need to hear it before they sink.

StenoImperium

Court Reporting. Unfiltered. Unafraid.

Disclaimer

“This article includes analysis and commentary based on observed events, public records, and legal statutes.”

The content of this post is intended for informational and discussion purposes only. All opinions expressed herein are those of the author and are based on publicly available information, industry standards, and good-faith concerns about nonprofit governance and professional ethics. No part of this article is intended to defame, accuse, or misrepresent any individual or organization. Readers are encouraged to verify facts independently and to engage constructively in dialogue about leadership, transparency, and accountability in the court reporting profession.

- The content on this blog represents the personal opinions, observations, and commentary of the author. It is intended for editorial and journalistic purposes and is protected under the First Amendment of the United States Constitution.

- Nothing here constitutes legal advice. Readers are encouraged to review the facts and form independent conclusions.

***To unsubscribe, just smash that UNSUBSCRIBE button below — yes, the one that’s universally glued to the bottom of every newsletter ever created. It’s basically the “Exit” sign of the email world. You can’t miss it. It looks like this (brace yourself for the excitement):

I am not a California reporter, but I find that SB 988 pretty interesting. My question is, is there a concurrent rule for attorneys to pay reporting firms within 30 days? I could see how it could be stressful for a small reporting firm to have to pay within 30 days without attorneys being held to the same standard.

LikeLike

Excellent question — and you’ve hit on a key point that’s often overlooked.

Under California Code of Civil Procedure § 2025.510(b), “the party noticing the deposition shall bear the cost of that transcription, unless the court orders otherwise.” In other words, the attorney (and their firm) who noticed the deposition is responsible for payment, not their client.

So while SB 988 requires reporting firms to pay court reporters within 30 days of invoice (even if they haven’t yet been paid by the attorney), there’s no corresponding statutory deadline requiring attorneys to pay the firm within a specific number of days. This creates a real cash-flow challenge for small agencies and independent contractors — they must pay promptly, but often wait 60–90 days (or longer) to be reimbursed.

Even if you’re not in California, this matters. Roughly one-third of all certified court reporters nationwide work here, and what happens legislatively in California often sets the precedent that other states follow. SB 988, AB 711, and other recent measures are likely to influence future legislation across the country — for better or worse. Several states could benefit by modeling the worker-protection and payment-timeliness aspects of California’s approach while improving on its gaps, like requiring reciprocal payment deadlines for attorneys.

In short:

✅ Reporters/firms must pay reporters within 30 days under SB 988.

⚖️ Attorneys are responsible for the cost under CCP § 2025.510(b), but no 30-day payment rule applies to them.

LikeLike