Subscribe to continue reading

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

Protecting the Record. Preserving Justice. Empowering Stenographers.

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

When Branding Outshines Accountability in Court Reporting

We’ve all asked it: “Why is she still here?” How does someone with no stenography credential, a trail of unanswered questions about labor practices, and a habit of quashing criticism remain a fixture in our profession?

Below is a candid look at the forces that keep her brand afloat—and what we can do to change the story.

In today’s attention economy, image often outranks substance. A slick website, vibrant social feeds, and high-energy events create the illusion of authority. For outsiders—or newcomers eager for motivation—that polish can look like leadership. Meanwhile, those of us doing the real work behind courtroom doors lack the time (or desire) to curate a brand narrative.

Result? The loudest voice, not the most experienced one, dominates.

Many stenos see the red flags—unpaid “volunteers,” corporate donations funneled into a for-profit venture, inflated success stories—but choose silence. Some fear backlash or ostracism; others just want to avoid drama. Every time we stay quiet, her platform grows taller. Silence isn’t neutrality; it’s passive endorsement.

Push back and you’re labeled “negative,” “jealous,” or “toxic.” Legal threats—like the recent trademark complaint leveled at my blog—turn the tables, framing the whistle-blower as the bully. It’s classic intimidation: shift focus from the allegations to the person raising them, and the real issues vanish from the feed.

Sponsorships, speaking fees, affiliate sales—profit flows to the person controlling the spotlight. Why abandon a cash-generating brand? Until the community stops clicking, sharing, and attending, the incentives favor staying put, credentials or ethics be damned.

Regulators, associations, and schools rarely police the “influencer” fringe. Unless a clear violation surfaces—tax fraud, false licensure—there’s little external pressure to step aside. That leaves accountability in our hands.

Because the equation works:

Polished branding – scrutiny + community silence = sustained influence and profit

She’s still here because the system rewards brand optics over professional substance—but only as long as we allow it. The moment enough stenos decide that ethical practice matters more than flashy marketing, the spotlight shifts. Let’s make that shift together.

Stenos, stay loud, stay factual, and above all, stay united.

***To unsubscribe, just smash that UNSUBSCRIBE button below — yes, the one that’s universally glued to the bottom of every newsletter ever created. It’s basically the “Exit” sign of the email world. You can’t miss it. It looks like this (brace yourself for the excitement):

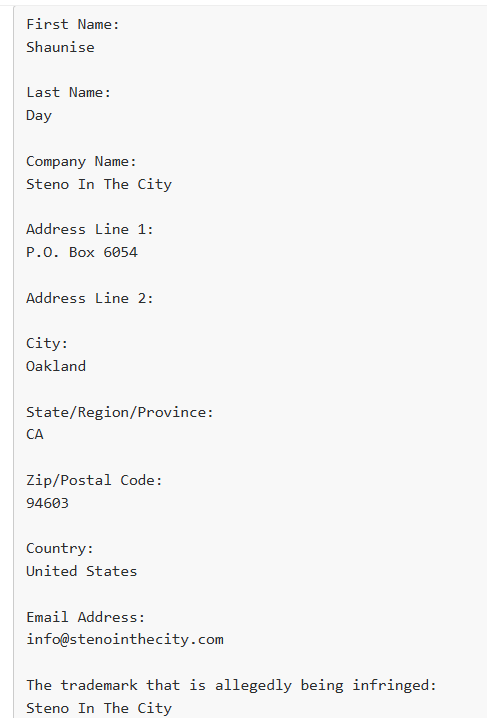

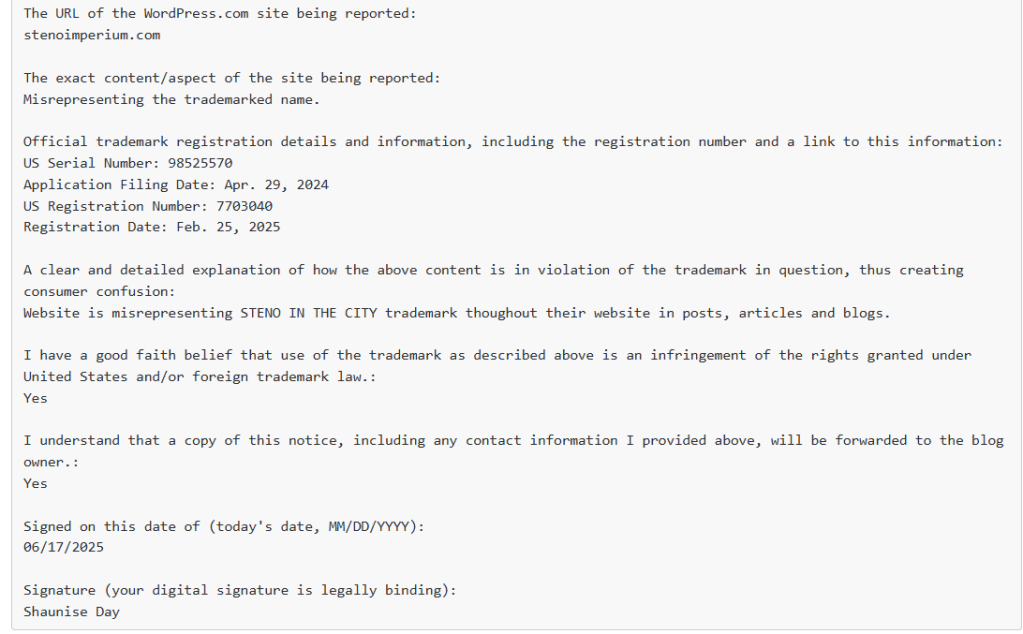

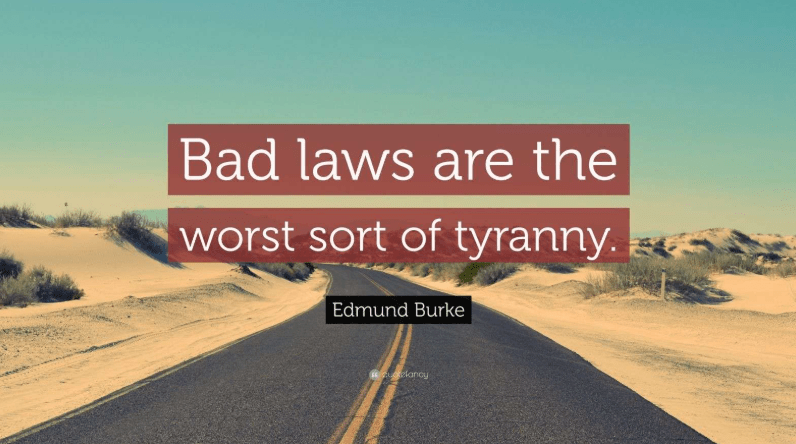

On June 19, 2025, I received an official complaint from WordPress regarding my blog, StenoImperium.com. The complaint was filed by an individual named Shaunise Day, who owns the brand “Steno In The City,” and it alleged that my use of the name in my blog content constituted trademark infringement.

This situation raises a larger issue about intellectual property, fair use, and how trademark law can sometimes be used not to protect a brand from confusion — but to stifle criticism, silence voices, and intimidate people who speak out.

Let me explain what happened, what the law actually says, and why this should matter to anyone who publishes commentary, criticism, or creative work online.

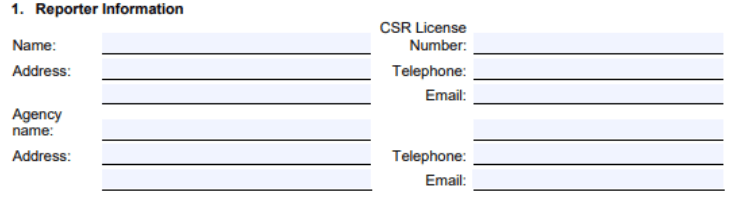

According to the report submitted to WordPress, Shaunise Day claimed that I was “misrepresenting the trademarked name” Steno In The City on my blog. She cited a U.S. trademark registration (Reg. No. 7703040, registered Feb. 25, 2025) and a filing date in April 2024.

It’s worth noting that the trademark for Steno In The City was only filed in April 2024 — immediately after I published my first exposé article raising serious questions about the brand’s operations. Looking back, it’s clear this wasn’t spontaneous — she’s been laying the trap for over a year. Since then, there’s been a slow, calculated pattern: curating a polished brand image, reframing criticism as “harassment,” and eventually weaponizing a newly minted trademark to try to shut me down.

This isn’t brand protection — this is legal strategy used to silence dissent. It’s a premeditated move that says more about controlling public perception than it does about protecting intellectual property.

She asserted that my use of the phrase in posts, articles, and blogs created “consumer confusion.” No specific examples were given — just the broad accusation that I was somehow impersonating her brand or benefitting from it.

Let’s be clear: I have never claimed to be Steno In The City. My blog is called StenoImperium — a name that is entirely distinct. I do not use her logo. I do not use her branding. I do not claim partnership or affiliation in any way.

What I have done is discuss the activities, public events, and decisions of her brand — sometimes critically, always honestly. That is not infringement. That is protected speech.

United States trademark law is designed to prevent consumer confusion and stop one business from profiting off the brand identity of another.

It does not prevent people from talking about a trademarked name.

If someone writes a blog post about how Amazon treats its workers, or a think piece about Nike’s global labor practices, they’re allowed to name those companies. That’s called nominative fair use — and it’s protected under the First Amendment.

To be clear, fair use of a trademark generally involves:

That’s exactly the standard I’ve followed. My references to “Steno In The City” have been made to identify the subject of my discussion — not to impersonate it.

One detail I want to highlight is that at the time of my writing, nowhere on the Steno In The City website did the trademark appear with a ® symbol or other notice that the name was federally registered. No disclaimer. No ownership mark. Nothing to indicate that I was using a federally protected name.

While such notice is not legally required for a trademark to be valid, it is required to pursue certain types of damages in court — especially those related to willful infringement.

This absence of notification reinforced what I believed at the time: that the name was being used as a brand, yes, but not one that had formal protection. I used it only to discuss what it publicly represents — not to exploit it.

What troubles me most is not the trademark claim itself, but the broader context of how it came about.

This is not the first time I have been the target of aggressive behavior from individuals connected to the Steno In The City brand. Over time, I have documented a growing pattern of online hostility, monitoring, and boundary-crossing behavior that, at best, feels like intimidation — and at worst, borders on harassment.

I won’t make sweeping claims of “cyberstalking” or “gangstalking” here — those are serious accusations that require serious legal evidence. But I will say this: when someone files a legal complaint not because they’re trying to protect a trademark, but because they want to remove unflattering commentary, that’s censorship disguised as IP enforcement.

And it’s not okay.

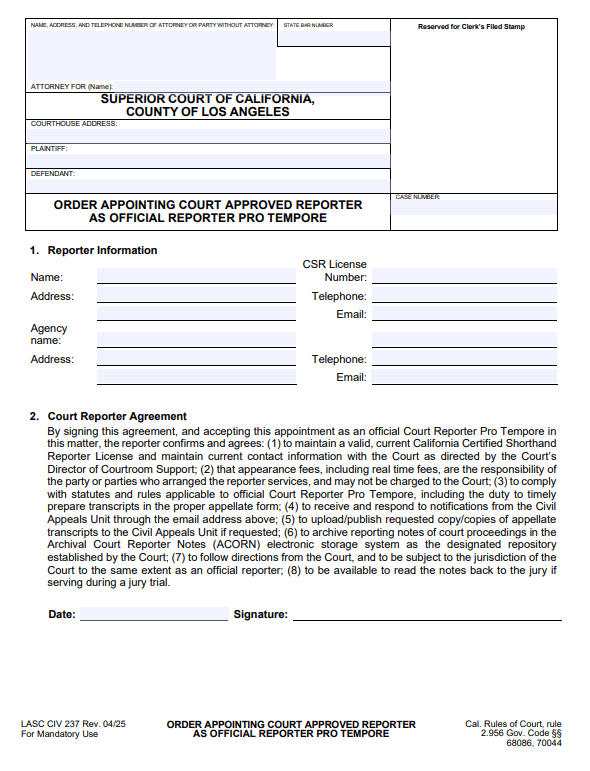

The trademark system should not be a weapon to suppress criticism. It should not be used to scare independent writers into silence. Yet increasingly, that’s what’s happening — not just to me, but to countless creators, journalists, and bloggers who dare to question public brands.

This trademark complaint appears less about actual brand confusion, and more about suppressing uncomfortable but truthful speech.

Because I care about integrity and clarity, I’ve taken several proactive steps:

In other words: I’m doing everything the law expects of a responsible writer. I’m honoring the trademark while exercising my right to speak truthfully about public matters.

This story isn’t just about me. It’s about the fragility of free expression in the digital age — and how easily our speech can be chilled by legal overreach.

When powerful voices use legal systems to intimidate smaller ones, it erodes public discourse. It sends a message that critique must be soft, that facts must be filtered, and that brands are above accountability.

We must push back against that.

I will continue to speak openly, honestly, and ethically about the world I work in — including the court reporting community and the brands that shape it. I encourage other independent voices to do the same.

Because speech is not infringement.

Truth is not defamation.

And critique is not a crime.

What Is a SLAPP?

SLAPP stands for Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation. It refers to legal threats or lawsuits designed not to win on legal grounds, but to intimidate critics into silence. Common in cases involving journalists, whistleblowers, or activists, SLAPPs misuse trademark, defamation, or copyright law to scare people away from speaking out. Many states have anti-SLAPP laws to protect public discourse from these tactics.

Looking back, it’s clear this wasn’t spontaneous — she’s been laying the trap for over a year. The trademark for Steno In The City wasn’t filed until April 2024 — conveniently, just after I published my first exposé. Since then, there’s been a slow, calculated pattern: curating a brand image, reframing critique as “harassment,” and finally weaponizing a newly minted trademark to try and shut me up.

This isn’t brand defense. This is legal entrapment designed to chill speech, and it couldn’t make her intentions any clearer.

It’s become increasingly clear that this individual’s priority is not accountability — it’s brand protection. Rather than address legitimate concerns about labor practices, nonprofit claims, and the exploitation of court reporters and students, she has chosen to focus her energy on controlling her public image.

Let’s be honest: this is a for-profit business operating under the guise of “community building.” That fact could not be more apparent. Many of us have supported her brand, shared her content, attended her events — often unpaid — believing it was for the good of the profession. But what are we actually supporting?

This person is not a stenographer. She has not worked in the field. From what I understand, she was a student who did not complete the program — part of the nearly 90% of students who don’t graduate from court reporting school. And yet, she’s positioned herself at the center of a profession she’s never been licensed in, building visibility, credibility, and financial gain on the backs of working stenos.

She expects the steno community to promote her brand, elevate her image, and support her endeavors — all while she profits. And now, faced with critique, instead of responding with transparency or reflection, she files a trademark infringement complaint in an apparent attempt to silence me.

This is not about confusion or brand misuse — it’s about control. It’s about preserving profit. It’s about stopping someone who’s asking uncomfortable questions.

If that doesn’t raise red flags, I don’t know what will.

I urge my fellow stenographers and students to take a closer look at where your support is going — and whether it’s truly building the profession, or just building a business for someone who is not part of it.

Instead of being open to accountability or taking responsibility for the serious concerns raised about her business practices — such as allegedly using unpaid labor improperly, misrepresenting a for-profit enterprise as a nonprofit, soliciting sponsorships under false pretenses, and running questionable “auctions” that some believe resemble gambling — her response has been to turn her energy toward silencing me.

Rather than addressing these public interest issues, she has chosen to target my livelihood, initiate a trademark complaint, and engage in what I believe is a pattern of harassment — including online monitoring, intimidation, and attempts to damage my reputation. I view this as a deeply unethical and potentially unlawful response to fair criticism.

So I ask: Is this the kind of leadership and behavior you want to align yourself with? If you’re aware of these allegations — and you continue to assist, promote, or support this activity — at what point does that become complicity? If these actions are part of a coordinated effort to silence critics and operate outside the law, some may reasonably ask whether that crosses the line into something even more serious — like organized misconduct or racketeering.

I leave that question open. But I won’t stop speaking about what I see. If you’ve ever faced similar attempts to silence your voice through misuse of trademark, copyright, or intimidation tactics, I see you — and I stand with you. Don’t back down. Know your rights. And keep speaking.

– StenoImperium

***To unsubscribe, just smash that UNSUBSCRIBE button below — yes, the one that’s universally glued to the bottom of every newsletter ever created. It’s basically the “Exit” sign of the email world. You can’t miss it. It looks like this (brace yourself for the excitement):

Imagine waking up tomorrow and no steno court reporters exist—not a single shorthand operator, no schools, no mentor networks, no equipment, no institutional backbone. What follows isn’t a tech-forward utopia, but a digital heist that collapses under its own weight.

Once all that’s gone, you can’t rebuild overnight. Unlike digital platforms that can be spun up quickly, court reporting relies on decades of skill and structure.

In our hypothetical “day zero,” digital “reporters” step in—but not to save the day. What users find is:

What remains is a deeply brittle network: superficially digital, but functionally rudderless.

Court reporting isn’t just typing. Consider:

When shorthand skill vanishes, our legal system loses these invisible yet vital safeguards.

Proponents of digital training often tout speed and low cost—but have you considered:

This churn isn’t innovation—it’s clearing out equity for expense.

With the ecosystem dismantled, two things become so much harder:

What starts as cost-cutting ends in legal fragility and societal harm.

Picture this scenario unfolding over days, weeks, months:

Resilience doesn’t come after collapse—it’s built beforehand.

The future of justice depends not on digital gimmicks, but on real skills, institutional knowledge, and a fully functional, human-centered ecosystem.

A world without stenographic court reporters is not futuristic—it’s a failed experiment, stripped of craftsmanship, structure, and fairness. What’s left is a brittle, expensive, unaccountable labor model built on cheap assumptions. Unless we act now—with awareness, support, and strategic investment—our “day without court reporters” becomes permanent.

The message couldn’t be more urgent: Our fragile ecosystem won’t survive a digital heist. Without steno, there’s no foundation—and restoring it later is an order-of-magnitude harder than preserving it today.

Because when stenos disappear… we all go with them.

***To unsubscribe, just smash that UNSUBSCRIBE button below — yes, the one that’s universally glued to the bottom of every newsletter ever created. It’s basically the “Exit” sign of the email world. You can’t miss it. It looks like this (brace yourself for the excitement):

Imagine a day in America where courtrooms are silent, not due to lack of proceedings, but because the protectors of the record have vanished. Not a single court reporter—no stenographers, no realtimers, no veterans with decades of institutional knowledge—is present to capture what’s being said, argued, decided. If this sounds like the dystopian premise of a film, think again. It’s already happening.

Just as the 2004 satirical film A Day Without a Mexican showed how essential, yet invisible, a marginalized group is to a society’s daily functioning, the disappearance of court reporters exposes a fragile legal ecosystem poised for collapse. “If you haven’t been paying attention to what’s been happening in the stenographic court reporting industry in the past decade,” one advocate warns, “then you are about to be hit by the proverbial bus… more like an atomic bomb extinction-level event.”

For decades, stenographic court reporters have held together the integrity of court records with a precision no digital recorder can replicate. Yet behind closed doors, powerful interests—backed by Silicon Valley money and private equity—have been waging a silent war against them, replacing trained professionals with digital recorders and AI-transcription models, all in the name of cost-saving and modernization. It’s a tech solution in search of a problem, and the consequences are starting to show.

Let’s be clear: digital court reporting is not equivalent to live stenography. As StenoImperium documented, Planet Depos and other mega-agencies recruited “digital reporters” off the street, only to discover a 320% turnover rate. Their new hires couldn’t meet the rigorous demands of accurate legal transcription. They tried to recruit trained stenographers to edit the mess—at cut rates. This revolving door of underpaid, undertrained labor results in massive inefficiencies, poor-quality transcripts, and delayed justice.

Worse, the so-called “shortage crisis” that helped fuel the digital takeover was largely a fabrication. The infamous 2013 Ducker Worldwide study predicted a shortfall of 5,500 court reporters by 2018, especially in California. But by 2024, California still boasts over 6,500 licensed stenographers—only a modest dip from 2012. The doom-and-gloom graph used by agencies to justify their pivot to digital was based on fictional data, no real census, and not a single interview with working court reporters. As Steno Imperium exposed, “It was invented, fabricated, concocted, made-up, complete fiction to fit their sales narrative.”

When you replace the tried-and-true human experts with algorithmic approximations, you lose more than people—you lose standards, ethics, oversight. Court reporters are trained professionals who manage realtime feeds, preserve decorum, and ensure an accurate, secure record. In contrast, digital systems require post-production editing by anonymous proofreaders and scopists—many overseas—who weren’t present during the proceeding and are not accountable for the final transcript. This breaks the chain of custody and jeopardizes appeals. As one court reporter noted, “Once you’ve got missing or incomplete transcripts, you might as well kiss your appeal goodbye.”

But this story gets darker. There’s a shortage—not of court reporters, but of the support systems that make their work sustainable. The manufacturing of steno machines is in decline. CAT software vendors are closing shop or switching focus to AI. Associations are dissolving. Schools are shutting down. Mentors are aging out, with no one to replace them. Once that expertise disappears, it’s gone forever.

If the traditional model is cast aside without a safety net, what’s left?

Greedy middlemen. Legal service agencies now gouge attorneys while paying court reporters less. Steno Imperium uncovered an agency that charged an attorney over $1,900 for a transcript the reporter invoiced at just over $200. That’s not inflation—that’s exploitation.

And then there’s accountability—or rather, the lack thereof. With digital recording, there’s no one to clarify who’s speaking, ask for repetitions, or flag audio issues in real time. There’s no guardian of the record, no ethical firewall, no licensed professional on the hook if something goes wrong. In high-stakes litigation, that should terrify us all.

So what happens next in a world without stenographers?

Turnaround times explode. Transcripts take weeks, sometimes months. Appellate courts are left in limbo. Trial outcomes can’t be reviewed. Legal errors go unchecked.

Access to justice erodes. Communities that rely on accurate, affordable court records—especially marginalized ones—are the first to suffer. Digital systems fail to meet ADA compliance. Language access becomes a nightmare. Costs soar.

And finally, institutional knowledge dies. Stenography is not a plug-and-play job; it is a craft, passed from master to apprentice. Without schools, mentors, or standardized licensing, there’s no way to rebuild the profession once it’s gone. As one advocate put it, “The extinction of stenographers would mean the extinction of a vast body of knowledge on the creation of the verbatim record.”

This is not inevitable. But we must act—now.

Because a day without court reporters is more than just quiet courtrooms—it’s the beginning of a legal system where truth is fungible, justice is delayed, and democracy is weakened.

We still have time to stop it. But we won’t get a second chance.

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

In a decision that’s been widely criticized as shortsighted and damaging, the Northern Alberta Institute of Technology (NAIT) has paused admissions to Canada’s only accredited Captioning and Court Reporting diploma program. This move, while perhaps appearing as a logistical or budgetary adjustment on the surface, poses an existential threat to the integrity of Canadian courts, accessibility services, and public media. It also offers the U.S. a rare opportunity to play a supportive role in preserving a profession vital to democracy and inclusion.

The NAIT program isn’t just another academic credential—it’s a rigorous, elite pipeline that trains the country’s most reliable human record-keepers. Students who are accepted often wait years for entry, only to spend two full years in intensive training, learning the art of real-time stenography: a skill that allows them to transcribe every word in fast-paced, overlapping conversations with near-perfect accuracy. Graduates earn the Certified Shorthand Reporter designation, a credential required for courtrooms, real-time TV captioning, and communication access for people with disabilities. Without this program, Canada has no domestic infrastructure to support the development of these professionals.

Imagine a murder trial where a key piece of testimony is muddled by cross-talk. Or a deaf patient attending a high-stakes consultation without real-time captioning. Or a government hearing where the transcript contains critical omissions. These are not hypothetical scenarios. They are real risks when trained stenographers are replaced with automated transcription tools, which routinely miss subtle speech nuances, misinterpret voices in noisy environments, and fail to request clarification when something is unclear.

Court reporters don’t just type—they verify, clarify, and deliver transcripts that hold legal weight. They are the responsible charge, the final authority over the accuracy of the record. They’re neutral, real-time arbiters of record, and their work underpins due process, journalistic integrity, and accessibility. The NAIT program’s suspension places this entire ecosystem at risk.

The Canadian Hard of Hearing Association has called this situation a “national crisis” in terms of accessibility. This isn’t just a matter of curriculum—it affects real people every day: those who rely on accurate captions in medical settings, in classrooms, and in courtrooms. It’s being glossed over as a niche issue when it’s a foundational one.

NAIT’s stated reasons for pausing the program—such as insufficient international student enrollment—are particularly troubling. This career requires a strong grasp of the English language and the ability to transcribe with grammatical precision at extremely high speeds. It was never designed as a mass-market program, and to hold it to those metrics is to fundamentally misunderstand what it trains people to do.

Claims of low graduation rates also deserve context. Court reporting students graduate not on a fixed timeline, but when they reach 225 words per minute with 95 percent accuracy—a standard upheld for public safety and legal reliability. That takes time, and rightfully so. Despite the difficulty, the program has consistently maintained a waitlist.

And as for job security? Many graduates have jobs lined up before they even finish the program. Since 2007, I’ve worked in closed captioning, CART, legal proceedings, and more—because this career opens doors, not closes them.

Artificial intelligence is not capable of doing what we do. NAIT’s decision, led in part by Tamara Peyton, appears rash, poorly researched, and out of sync with the school’s responsibility to serve the public good.

The North American court reporting profession is already grappling with a looming crisis: a massive wave of retirements with no new generation ready to take over. In Canada, nearly half of the approximately 7,900 court reporters are over the age of 50. The situation is similarly dire in the U.S., where estimates suggest a shortage of more than 5,000 reporters in the coming years. Yet instead of doubling down on training and recruitment, NAIT’s pause effectively shutters the only pipeline for new professionals in Canada.

This is not just a Canadian problem—it’s a cross-border issue that invites American institutions, courts, and organizations to reflect on the importance of this craft and consider how to lend support.

The National Court Reporters Association (NCRA) is the professional body that accredits court reporting programs in North America. NAIT is the only Canadian institution that holds this prestigious accreditation. Losing this program would mean losing NCRA’s presence in Canada and a critical North American training partner.

Contrary to earlier impressions, the NCRA has taken formal action. On June 3, 2025, NCRA President Keith R. Lemons, FAPR, RPR, CRR (Ret.) sent a letter to NAIT President Laura Jo Gunter and Alberta Minister Myles McDougall, urging them to reconsider the decision to pause the Captioning and Court Reporting (CCR) program. In the letter, the NCRA emphasized that cancelling the program would worsen Canada’s shortage of court reporters and captioners—roles essential for justice and communication access, especially for the deaf and hard of hearing communities. They offered to collaborate with NAIT on hybrid or alternative delivery models to keep the program viable.

That same day, the NCRA received a supportive response from the office of Alberta Legislative Assembly member David Eggen, who confirmed that he had also contacted the Minister of Advanced Education to advocate for the program’s continuation.

While this advocacy effort was not widely publicized at first, it now stands as a meaningful step that reflects the NCRA’s recognition of the crisis and willingness to act.

Still, further engagement and visibility are needed. NAIT has not yet reversed its decision, and more robust, public-facing support remains critical to keeping this program alive.

Here are five practical and impactful steps the NCRA can and should take to support NAIT and the profession:

The NCRA should release a formal statement urging NAIT to reinstate its court reporting program. They must frame this issue as a matter of justice, accessibility, and professional integrity. Engaging the public and policymakers in this conversation is essential to building pressure on institutional decision-makers.

If NAIT is pausing the program due to budgetary or administrative constraints, the NCRA can offer direct support: sharing resources, providing teaching materials, and possibly co-developing online components to reduce overhead. A North American educational partnership could ease institutional burdens while keeping the program alive.

Students currently enrolled or accepted into NAIT’s program are left stranded. The NCRA should facilitate transfer agreements with U.S. programs, offer scholarships or funding for displaced students, and clarify credentialing options so Canadian students can still enter the profession.

The NCRA can commission research on the cost of losing human stenographers in Canada—from legal liability and transcription errors to increased reliance on foreign or AI-based services. Data-backed arguments can strengthen advocacy efforts and demonstrate the program’s value beyond academia.

The NAIT crisis is an opportunity to deepen U.S.-Canada professional ties. The NCRA could lead in forming a Canadian Court Reporting Advocacy Task Force, offer joint conferences and training, and expand its international focus to ensure Canada remains a stakeholder in the profession.

American institutions and professionals can also step up. This isn’t about taking Canadian jobs—it’s about reinforcing a vital profession across borders:

This is not just about career training; it’s about democratic infrastructure. Without qualified human court reporters, the legal system becomes vulnerable to error, manipulation, and bias. Without live captioning, millions of people with hearing loss lose access to communication. Without CART providers, equitable access to education and healthcare vanishes.

NAIT’s decision strips away a vital support beam from Canada’s legal and media systems. But worse still, it sends a message that precision, accessibility, and truth aren’t worth investing in. That’s unacceptable.

NAIT’s decision to suspend the only accredited stenography program in Canada overlooks a crucial truth: court reporters do more than work in courts. Many provide real-time captioning and transcription for people who are deaf or hard of hearing, serving in hospitals, classrooms, and beyond.

This is not a convenience issue. It’s a matter of basic human rights.

For nearly two decades, I’ve delivered weekly transcripts in scenarios with layered speech, thick regional accents, and fast-paced conversation—linguistic challenges that routinely stump AI. These skills can’t be replicated by machines. The program’s removal not only fails students, but fails the public.

NAIT is considering turning this rigorous, credentialed program into a non-credit course or cutting it entirely. Either option erodes a vital public service and leaves over 3 million Canadians who rely on captioning and CART services without future support.

🚨 Why this matters:

We cannot allow accessibility to be sidelined by short-term metrics or administrative miscalculations.

Take action now. Contact the following to voice your concerns:

Please also copy the Canadian Hard of Hearing Association (CHHA National) in your correspondence.

Help protect our collective right to equitable communication.d inclusion.

NAIT must reinstate the Captioning and Court Reporting diploma. The NCRA must rise to meet this moment. And American professionals must lend their voices to protect a profession that safeguards justice and inclusion on both sides of the border.

If we let this program vanish without a fight, we trade accuracy for error, inclusion for exclusion, and a proud Canadian profession for outsourced guesswork. But if we act together—decisively and vocally—we can save more than a school. We can save the standard.

Let’s make sure the guardians of the record are not silenced. Because when they are, the truth is the first casualty.

***To unsubscribe, just smash that UNSUBSCRIBE button below — yes, the one that’s universally glued to the bottom of every newsletter ever created. It’s basically the “Exit” sign of the email world. You can’t miss it. It looks like this (brace yourself for the excitement):

In recent months, a noticeable shift has taken place across Facebook Groups dedicated to court reporters. Posts are no longer proudly authored with names and credentials. Instead, a growing number are tagged with the familiar gray label: “Posted anonymously.”

At first glance, it might seem harmless—perhaps someone asking a sensitive question or navigating a difficult situation. But scroll long enough, and a troubling pattern emerges: reporters are afraid to speak openly. They worry about backlash, gossip, being reported to their agencies, or worse—being doxxed and targeted.

The rise of anonymous posts in these groups isn’t just a behavioral shift; it’s a red flag. It signals a deeper, systemic dysfunction within the online culture of court reporting—and a growing obsolescence of the platforms we once trusted to connect and support us.

The “post anonymously” feature on Facebook was designed as a way to encourage open dialogue about personal or vulnerable issues. But in court reporting communities, it’s become a shield against professional retaliation.

Reporters use it to:

The fact that these posts are anonymous doesn’t make them less important. In fact, it makes them more urgent. What does it say about a profession when members can’t ask for help or express doubt without fearing consequences?

Many who work in court reporting will quietly admit what some say out loud: the culture can be brutal. Gossip is rampant. Bullying goes unchecked. People take screenshots of group posts and share them in backchannels. In extreme cases, reporters have been tattled on to their agencies or clients, resulting in job loss or damaged reputations.

This behavior doesn’t just create a toxic atmosphere—it actively undermines the profession’s future. Talented new reporters, overwhelmed by the hostility, either go silent or leave. Experienced reporters stop mentoring, choosing self-protection over engagement.

An anonymous poster recently wrote, “I love the work, but I’m terrified of the people. I’ve never seen a profession where everyone is so eager to destroy each other.” And judging by the number of supportive comments (and the fact it was posted anonymously), they’re far from alone.

Once a vibrant hub for sharing knowledge and community support, Facebook Groups for court reporters are now increasingly dysfunctional. That’s not just due to the toxic culture—they’re also suffering from platform decay.

These issues make the platform functionally obsolete for professionals who need timely, reliable, and safe spaces to learn and grow. And when you combine that with the social toxicity, it’s no wonder people are opting for anonymity—or leaving entirely.

When a professional community sees a surge in anonymous interaction, it’s not a sign of strength. It’s a symptom of deep psychological unsafety.

Anonymity is supposed to encourage vulnerability—but here, it’s being used to avoid punishment. Reporters don’t trust the space. They don’t trust their peers. And many no longer trust that their honest questions or opinions won’t be weaponized against them.

This isn’t sustainable. A profession where people must hide to participate is a profession at risk.

There’s a choice to be made—individually and collectively. Do we continue to tolerate a culture where fear rules the conversation? Or do we take steps to rebuild a professional environment where respect, mentorship, and real support are the norm?

Here’s where we can start:

Court reporting is already under pressure—from automation, shrinking budgets, and public misunderstanding of the profession’s value. The last thing it needs is self-inflicted damage through a hostile online culture that isolates and intimidates its own members.

The explosion of anonymous posts isn’t just a curiosity—it’s a message. People are desperate for help, for connection, for safety. The fact that they don’t feel they can get that under their own name should alarm everyone who cares about the future of this profession.

Facebook may still be the most active platform for court reporters right now. But if this trend continues—if fear continues to outweigh trust—it won’t matter how many members are in the group. The real conversation will be happening elsewhere, behind closed doors, in whispered chats, or not at all.

And if that happens, we won’t just lose a Facebook Group—we’ll lose one of the few remaining spaces where this fractured profession could still come together.

The content of this post is intended for informational and discussion purposes only. All opinions expressed herein are those of the author and are based on publicly available information, industry standards, and good-faith concerns about nonprofit governance and professional ethics. No part of this article is intended to defame, accuse, or misrepresent any individual or organization. Readers are encouraged to verify facts independently and to engage constructively in dialogue about leadership, transparency, and accountability in the court reporting profession.

***To unsubscribe, just smash that UNSUBSCRIBE button below — yes, the one that’s universally glued to the bottom of every newsletter ever created. It’s basically the “Exit” sign of the email world. You can’t miss it. It looks like this (brace yourself for the excitement):

The California Court Reporters Board (CRB) has quietly enacted a policy change with major implications for the court reporting industry and education community: it has removed the names of schools from official pass lists of the California Certified Shorthand Reporter (CSR) exam.

This administrative decision may seem minor on the surface, but it has sparked significant concern among the few remaining court reporting schools in the state—many of whom are already struggling under regulatory burdens. The omission of school names from CSR reports severs a critical connection between student outcomes and the institutions that trained them, undermining transparency, accountability, and the future of court reporting education in California.

Perhaps the most frustrating aspect of the CRB’s decision is that it came without any advance notice or communication to the schools affected. Programs that have worked for years to prepare students for the CSR exam were not informed of the change, nor given an opportunity to provide feedback. The decision was simply implemented, leaving educators to discover the shift on their own.

Historically, these pass lists served multiple purposes. Not only did they confirm who passed the rigorous licensing exam, they also publicly recognized the institutions that trained those candidates. This transparency has long been a benchmark of credibility and performance for schools. Now, that institutional recognition has been erased.

For schools, public identification in CSR pass lists is more than just a matter of pride—it’s a vital part of their operations. School-specific pass rates are essential for:

One court-reporting school in California even used its track record of student performance on the CSR exam to achieve full accreditation. That would be virtually impossible under the new CRB policy, which anonymizes data and leaves schools without public proof of success.

The change in reporting comes at a particularly precarious time for the court reporting industry. While the overall number of vocational and trade schools in California has remained relatively stable or even grown in some sectors, the number of court reporting programs has sharply declined over the last two decades.

At one time, California was home to more than a dozen court reporting schools. Today, there are only 7 or 8 still operating in the state. That contraction is not due to a lack of student interest or industry demand—the need for court reporters remains high, and many positions go unfilled. Instead, schools have closed or relocated because of increasingly hostile business conditions created by the state’s regulatory environment.

Court reporting programs—most of which are private vocational institutions—have faced repeated audits, high compliance costs, and the unpredictable demands of the California Department of Education. Accreditors have pulled out of the state entirely in some cases, unable to navigate the regulatory red tape. Without accreditation, many schools lose eligibility for financial aid programs, insurance recognition, and other support systems, forcing them to shut down.

Unlike traditional public or nonprofit educational institutions, private court-reporting programs operate on tight budgets and depend heavily on transparency to remain competitive. Public performance data, like CSR exam outcomes, helps them validate their existence in a niche but vital field. Removing that information from public view could deliver the final blow to some of the state’s last-standing programs.

The timing of this change couldn’t be worse. California—and the country more broadly—is in the midst of a court reporter shortage. Retirements are outpacing new entries to the field, and the pipeline of qualified graduates is drying up. According to industry associations, the demand for court reporters is not expected to slow down any time soon, especially in civil and criminal courts where live stenographers remain essential.

In this context, the CRB’s policy of withholding school data is not just bureaucratically shortsighted—it’s potentially damaging to the long-term viability of the profession. With fewer schools and fewer students, the industry needs every possible incentive to attract new talent. Highlighting where students succeed could help encourage future enrollment. Instead, the state is opting to obscure that information, making it harder to promote and defend these critical educational programs.

Transparency in education helps all stakeholders: students can make better-informed decisions, schools can market their success, employers can trust the competency of graduates, and state agencies can monitor the effectiveness of licensing pipelines.

Without this visibility, it becomes harder to assess whether educational programs are effective. It also reduces accountability for both the schools and the board itself. If pass rates dip, no one can trace whether it’s due to declining instruction quality or increased difficulty in the exam. If rates improve, schools can’t showcase their success to new students or accreditors.

It’s also worth noting that the CRB, as a state agency, has an obligation to support and sustain the court reporting pipeline—not stifle it through administrative opacity.

If California is serious about addressing the court reporter shortage and maintaining a robust pipeline of well-trained professionals, it must reverse this policy. The CRB should:

Moreover, broader state leadership—especially within the Department of Consumer Affairs and the Legislature—should investigate how regulatory decisions are influencing school closures in high-need fields like court reporting.

The removal of school names from CSR exam results may have seemed like an administrative formality to the CRB, but it has real consequences for the few remaining court-reporting programs in California. At a time when the industry is fighting to survive and rebuild, this decision undercuts the very institutions working to train the next generation of professionals.

If not reversed, this policy risks accelerating the decline of court-reporting education in California—at the exact moment the profession needs it most. Transparency and partnership, not secrecy and silence, are what the industry deserves.

The content of this post is intended for informational and discussion purposes only. All opinions expressed herein are those of the author and are based on publicly available information, industry standards, and good-faith concerns about nonprofit governance and professional ethics. No part of this article is intended to defame, accuse, or misrepresent any individual or organization. Readers are encouraged to verify facts independently and to engage constructively in dialogue about leadership, transparency, and accountability in the court reporting profession.

***To unsubscribe, just smash that UNSUBSCRIBE button below — yes, the one that’s universally glued to the bottom of every newsletter ever created. It’s basically the “Exit” sign of the email world. You can’t miss it. It looks like this (brace yourself for the excitement):

When aspiring court reporters hear horror stories about the Certified Shorthand Reporter (CSR) exam—like students who sit for it seven times before passing—it can stir up fear and doubt. One student recently asked a seasoned 20-year veteran of the field if those tales were true: “Seven times???? Would like to pass the first time.”

The court reporter’s reply was candid, grounded, and full of both personal insight and tough love. She admitted to passing the CSR on her second try, but her first attempt was sabotaged not by a lack of skill, but by her insistence on using a typewriter. “Stupid move on my part,” she said bluntly. That alone is a powerful lesson: success often hinges on both preparation and making smart, up-to-date choices with technology and strategy.

But the bigger takeaway from her story is how you approach school, practice, and professional development. According to her, “Plenty of people pass their first time.” The deciding factor? Discipline. Focus. A willingness to work smarter—not just harder—and a refusal to settle for mediocrity.

The CSR isn’t some impossible mountain that only the lucky few can summit. Yes, test anxiety is real. Yes, nerves can get the best of even the most prepared student. But blaming the test, the school, or fate isn’t the path to success. Preparation is.

The veteran recalls pulling the steno notes of a fellow student who had been in court reporting school for ten years and wasn’t making progress. What she saw shocked her: “Her notes were a mess, didn’t resemble any correct steno outlines, and lots of shadows. She was writing slop.”

That student eventually quit—not because she lacked intelligence, but because she lacked discipline and a willingness to self-correct. And, unfortunately, she wasn’t alone. “There are a lot of students like her,” the reporter explained. “With no work ethic, without the need to perfect their writing, and will show up every day and write pure slop.”

In court reporting, simply showing up isn’t enough. Mastery requires more than time—it demands excellence.

The most striking part of this veteran’s insight wasn’t the warning about bad habits—it was the secret to her own success: “I approached school like a D1 athlete.”

For those unfamiliar, Division I athletes are the elite of college sports. Their days are tightly scheduled around training, practice, competition, and recovery. Every rep, every drill, every meal is intentional. The margin for error is thin, and expectations are high. That’s exactly the mindset the court reporter brought to her training.

Here’s what that looks like when applied to court reporting school:

“I gave it 120% every day. My time in class was laser focused.” This is key. It’s not just about how much time you spend practicing—it’s about how well you use that time. Passive listening, sloppy shorthand, distracted practice sessions—those won’t get you anywhere.

In class, treat every speed-building drill like a game-day performance. Minimize distractions. Analyze your weaknesses. Seek feedback. Push yourself to write with accuracy and purpose.

“I kept my standards high and I was very hard on myself in terms of expectations for progress.”

Elite performers don’t wait for external deadlines. They set personal benchmarks and push to exceed them. Make your own timeline for passing each speed test. Track your errors. Record your dictations and play them back critically. Push yourself harder than any instructor ever will.

After school, the veteran would pack up and head to a movie or lunch with friends. “I never took [my bag] out to practice.” To some, this might sound like slacking—but it’s actually strategic.

Just like athletes need recovery days, your brain needs downtime. When you work intensely during class, stepping away afterwards helps consolidate memory, avoid burnout, and keep your passion alive. That only works, of course, if your class time is truly effective.

There were times when this seasoned reporter did take her bag home and practice—“when I was falling behind my self-imposed schedule.” That’s an important nuance. Practicing outside of class wasn’t a daily grind; it was a tactical move when progress slowed.

Many students panic and start practicing blindly, drilling the same mistakes into muscle memory. Instead, practice with intention. Address specific weaknesses. Use dictations that challenge your accuracy. Practice isn’t about clocking hours—it’s about gaining skill.

The CSR is hard—but not impossible. The stories of people failing it seven times are real, but they’re not inevitable. They’re often the result of poor habits, low standards, and an unwillingness to course-correct.

This veteran reporter didn’t sugarcoat the reality: “I can tell you exactly why someone would take that long to get through school and why people fail. That’s easy to answer.”

The answer isn’t some mystery. It’s discipline.

Here are some steps to adopt the elite mindset of a Division I athlete in your court reporting journey:

Anyone can go through the motions of court reporting school. But if you want to pass the CSR on the first try—or simply graduate faster—you’ll need more than attendance and effort. You’ll need drive. Standards. Precision. Grit.

Think like a D1 athlete. Every class is a competition. Every test is a proving ground. And every minute spent writing should serve a purpose. That’s the difference between someone who passes the CSR once—and someone who never gets there.

Show up. Lock in. And aim higher.

The content of this post is intended for informational and discussion purposes only. All opinions expressed herein are those of the author and are based on publicly available information, industry standards, and good-faith concerns about nonprofit governance and professional ethics. No part of this article is intended to defame, accuse, or misrepresent any individual or organization. Readers are encouraged to verify facts independently and to engage constructively in dialogue about leadership, transparency, and accountability in the court reporting profession.

***To unsubscribe, just smash that UNSUBSCRIBE button below — yes, the one that’s universally glued to the bottom of every newsletter ever created. It’s basically the “Exit” sign of the email world. You can’t miss it. It looks like this (brace yourself for the excitement):

In the rush to embrace new technologies, the court reporting industry is undergoing a disruption that, for many professionals, feels more like destruction. AI transcription tools, digital reporters, and automated editing systems are being marketed as sleek, efficient solutions to modern demands. But behind the scenes, the very people who hold the system together—scopists, proofreaders, and certified court reporters—are being pushed out, underpaid, and overworked. The result is a deteriorating standard of transcript quality and a looming crisis of workforce attrition that threatens the entire profession.

Tech vendors and some reporting agencies are touting AI and digital audio systems as faster and more cost-effective than traditional stenographic reporting. But anyone actually working with these transcripts knows better. Yes, the initial capture might be immediate. But getting from rough digital file to final, usable transcript is anything but fast. The process of reviewing, correcting, and editing AI-generated content—or audio-based recordings transcribed by unskilled operators—requires immense human labor, often more than it would take to simply do the job right the first time through stenographic methods.

Proofreaders and scopists are now being handed what can only be described as messes: raw files riddled with inaccuracies, lacking punctuation, filled with untrans and dropped sentences. These aren’t polished drafts in need of a final check. They’re barely coherent transcripts that require hours of editing—and often without the benefit of audio or the original steno file. These workers are effectively being asked to do multiple jobs for the rate of one—and many are saying no.

The fallout is predictable: skilled scopists and proofreaders are quitting in droves. The work has become thankless and unsustainable. What used to be a vital second set of eyes on a nearly-final document has devolved into being the sole quality control checkpoint for entire transcripts—often at sub-minimum wage rates. One former court reporter, now working as a proofreader, recently described earning just $8 an hour due to the volume of errors per page and lack of formatting in the files she received.

This isn’t proofreading—it’s unpaid scoping. And it’s being done under unrealistic expectations, inadequate pay, and without the professional respect the role deserves. If this trend continues, there will be a serious shortage of proofers and scopists willing to work under these conditions, compounding delays, increasing costs, and further degrading the quality of legal transcripts.

Let’s be clear: scopists and proofreaders are essential, but they cannot replace court reporters. Court reporters are the official custodians of the record. Their real-time transcription, accuracy, and ability to manage proceedings are what ensure the integrity of legal documentation. Replacing them with unregulated digital recording systems or AI tools, then attempting to “clean it up later,” not only shifts legal responsibility away from the point of capture but also introduces a minefield of errors and inconsistencies.

Scopists and proofers work downstream, and they do not hold legal responsibility for transcript accuracy. Expecting them to retroactively reconstruct what happened in a deposition or courtroom—often with partial information—is both unfair and impractical. Moreover, the professionals being handed this burden aren’t being paid enough to justify their role becoming the new frontline of accuracy.

Ironically, this technological “advancement” is a giant leap backward. Fifty years ago, in the 1970s, dictation machines and typists were the norm. Court reporters would dictate their notes, and typists—paid fairly for their time—would transcribe them. In 1970, transcript rates averaged around $3.00 per page. Adjusted for inflation, that’s about $18 per page today. In that economic context, the cost of having multiple humans touch a transcript—reporter, typist, editor—was manageable.

But today’s transcript rates haven’t kept up with inflation, while expectations have ballooned. The industry is now attempting to achieve the same level of quality at one-third of the cost, with three times the workload, and none of the skilled infrastructure in place. It’s a financial model that is fundamentally unsustainable. What worked 50 years ago at fair wages doesn’t work today at cut-rate prices.

While AI and digital solutions are sold as cost-cutting measures, the real-world math tells a different story. Instead of paying one highly trained court reporter to scope and deliver a polished transcript, firms are now paying:

All told, that adds up to more time, more labor, and more cost—often two to three times what a single steno reporter would charge to produce a transcript that requires minimal revision. The perceived savings evaporate quickly, and the additional burden placed on support professionals threatens to collapse the system entirely.

The driving force behind the AI and digital reporting movement isn’t the professionals who actually create the record—it’s the national agencies, vendors, and software companies like Stenograph and Procat, many of whom have never set foot in a deposition or courtroom. These decision-makers build tools based on abstract workflows, not firsthand experience, and they lack a true understanding of the skill, responsibility, and precision that court reporters bring to the job. Their motivation is clear: reduce costs by eliminating highly skilled reporters and replace them with cheaper labor and digital tools, assuming the transcript can still be cobbled together downstream. But they grossly underestimate the complexity of the work and the economic chain it supports. By cutting court reporters, they believe they’re saving money—when in reality, they’re destabilizing a fragile, interdependent system of subcontracted professionals who are now re-evaluating their worth.

Scopists and proofreaders, traditionally supporting court reporters by editing already-clean steno files, are now being asked to clean up disorganized, error-ridden transcripts produced by AI and digital recorders. This isn’t just scoping anymore—it’s reconstructive transcription, and many scopists are demanding higher rates accordingly. While a court reporter’s scoped file might command $1.25 per page, the cleanup required for digital/AI transcripts often justifies $4.00 per page or more. And here’s the ripple effect: scopists now know they can earn more working on AI/digital jobs, so they’re less inclined to accept lower-paying work from court reporters, unless those rates rise too. Reporters, in turn, are being squeezed from both ends—expected to deliver quality while paying more to subcontractors who are understandably unwilling to shoulder the burden without fair compensation. The economics are shifting rapidly, not by design, but as a consequence of a profit-driven system that failed to account for the real labor behind the transcript. But once that shift occurs, court reporters themselves will have no choice but to raise their rates to cover the increased subcontracting costs—and that introduces a new layer of economic tension.

Attorneys and law firms are already pushing back on what they perceive as skyrocketing court reporting fees, but what many don’t realize is that reporters themselves are often still earning what they earned 30, even 50 years ago. The real cost increases are coming from the big national agencies—many of which are now doubling or tripling rates to clients while failing to pass any meaningful portion of that markup downstream to the professionals doing the work. So while the legal industry is being told that technology is the path to savings, what’s actually happening is a redistribution of cost and profit that leaves the professionals underpaid, overburdened, and increasingly unwilling to stay in the game. It’s not just inefficient—it’s unsustainable.

So while the legal industry is being told that technology is the path to savings, what’s actually happening is a redistribution of cost and profit that leaves the professionals underpaid, overburdened, and increasingly unwilling to stay in the game. It’s not just inefficient—it’s unsustainable. And for many court reporters, it’s starting to feel intentional. The big national agencies and vendors profiting from this shift aren’t merely ignoring the fallout—they’re accelerating it, creating conditions so unworkable that experienced reporters are being squeezed out by design. Whether by negligence or strategy, the outcome is the same: the quiet elimination of skilled stenographers under the guise of innovation.

Seasoned proofreaders are now voicing frustration and burnout. Many express disbelief at the lack of quality in the work they’re handed—some of it coming not just from digital reporters, but even from credentialed steno reporters who’ve abandoned scoping altogether to save money. This erosion of pride and professionalism is disheartening. Longtime reporters once took ownership of every transcript that carried their name. Now, there’s a growing trend of outsourcing the bulk of the work to others, and paying them poorly to do it.

This commodification of skill is driving experienced professionals away—and once they’re gone, they won’t return. We’re not just losing manpower; we’re losing institutional knowledge, quality control, and the mentorship that once raised the bar for newcomers in the field.

The court reporting industry must take a hard look at what’s happening. Technology can be a tool, but it should never be a substitute for skill, ethics, and responsibility. We must:

We must also reject the dangerous idea that AI or digital tools can fully replace human oversight. They can supplement the process, but without skilled hands guiding them, they will never be capable of meeting the high standards legal proceedings demand.

The foundation of justice is a clear, accurate, and timely record. That record is only possible because of the professionals who create, refine, and verify it at every stage. As the industry leans into automation and outsourcing, it risks losing the very precision and trustworthiness that give transcripts their value.

If we continue down this path, we won’t just be replacing humans with machines—we’ll be replacing integrity with convenience, and professionalism with chaos. And that’s a price none of us can afford.

The content of this post is intended for informational and discussion purposes only. All opinions expressed herein are those of the author and are based on publicly available information, industry standards, and good-faith concerns about nonprofit governance and professional ethics. No part of this article is intended to defame, accuse, or misrepresent any individual or organization. Readers are encouraged to verify facts independently and to engage constructively in dialogue about leadership, transparency, and accountability in the court reporting profession.

***To unsubscribe, just smash that UNSUBSCRIBE button below — yes, the one that’s universally glued to the bottom of every newsletter ever created. It’s basically the “Exit” sign of the email world. You can’t miss it. It looks like this (brace yourself for the excitement):

The content on this blog represents the personal opinions, observations, and commentary of the author. It is intended for editorial and journalistic purposes and is protected under the First Amendment of the United States Constitution.

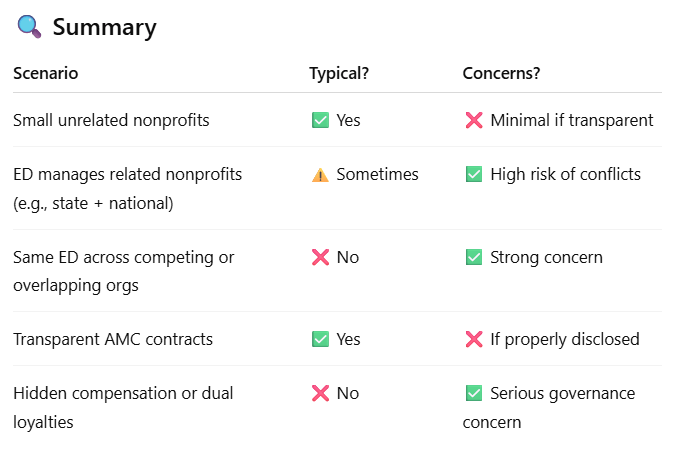

In most industries, transparency and neutrality are non-negotiable values—especially when it comes to leadership in professional associations. But in the court reporting world, one man holds a surprising amount of influence: Dave Wenhold, Executive Director of both the National Court Reporters Association (NCRA) and the Illinois Court Reporters Association (ILCRA).

What’s more? Wenhold, through his firm Miller Wenhold Association Management, has held executive roles in multiple state and industry associations—including the New York State Court Reporters Association (NYSCRA) —spanning industries, states, and causes far beyond stenography.

This reality has led many professionals to ask an uncomfortable but necessary question:

Is this structure fair to the rest of the profession? Or are we looking at a conflict of interest hiding in plain sight?

Being Executive Director of both the national and one of the most prominent state associations is unusual. It’s not illegal. It’s not necessarily unethical on its face. But it’s definitely unprecedented—and more importantly, it’s loaded with risk.

The NCRA is tasked with serving all states equally. It creates national policy, directs federal advocacy, is entrusted with distributing attention and resources across all its state-level partners, and helps guide the strategic future of the stenographic profession. ILCRA, meanwhile, advocates for a single state’s interests of one specific region.

With one individual at the helm of both, how can members be sure the national agenda isn’t being influenced by local priorities? Are other states receiving the same level of access, attention, and support that Illinois might be?

Dave Wenhold serves as the Executive Director for multiple associations beyond the NCRA and ILCRA. Through his firms, Miller Wenhold Association Management, and Miller Wenhold Capitol Strategies, he holds executive roles in various organizations across different industries.

For instance, he has also been involved with the New York State Court Reporters Association (NYSCRA). According to a detailed account on Stenonymous.com, concerns were raised during his tenure about record-keeping and management practices, leading to operational challenges for the association after his departure.

In addition to these roles, Wenhold’s firm manages or has managed associations such as:

This list is not exhaustive, as the full number of associations for which Dave Wenhold directly or indirectly serves as Executive Director is not publicly known.

This extensive portfolio raises fair questions about the potential for divided attention and the ability to dedicate sufficient focus to each organization’s unique mission.

While holding executive positions in multiple organizations is not inherently unethical, it does necessitate a high level of transparency, accountability, and clear delineation of responsibilities to ensure that each organization’s interests are fully represented and protected. The concerns raised highlight the importance of evaluating governance structures and leadership roles to maintain trust and effectiveness within professional associations.

That’s a broad list, with very different missions. It’s entirely fair to ask:

If you’re a board member or active volunteer in another state association—say, Texas, Florida, or New Jersey—you might rightly wonder:

Even if decisions are made in good faith, the perception of favoritism is real—and perception alone can be damaging.

How much bandwidth does one person—or one management company—really have?

Can one executive simultaneously advocate for the national interests of court reporters, oversee local chapter affairs, and maintain focus on entirely unrelated fields—all while staying up to speed on stenographic policy battles, member needs, and emerging threats like digital transcription encroachment?

Every professional association exists to serve its members. That includes:

But when so much administrative power is concentrated in one person—or one firm—accountability becomes difficult. Mistakes can be repeated across organizations. Conflicts can go unchecked. Priorities can become blurred.

And worse: members often don’t even know it’s happening.

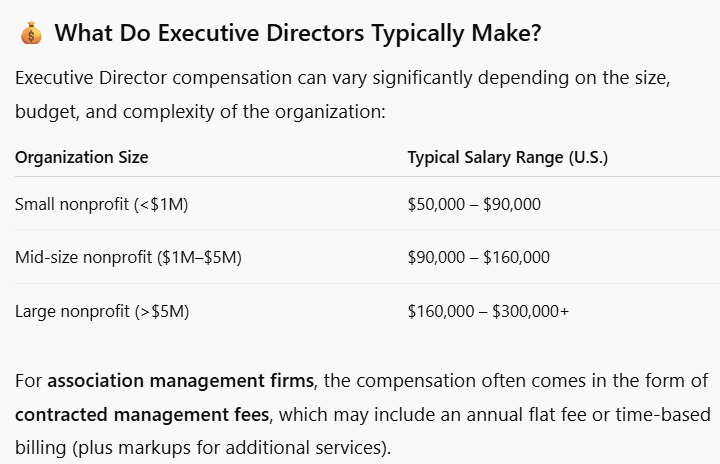

In nonprofit governance, executive compensation is always a critical metric. It should reflect:

But when an executive holds multiple paid roles, the conversation shifts from what’s fair to what’s appropriate. That’s especially true in the case of Dave Wenhold, who is not only the Executive Director of the NCRA, but also of the ILCRA—and several other unrelated associations.

According to the NCRA’s IRS Form 990 filings, Wenhold’s compensation as of the latest reports was:

These filings are public and reflect the industry-appropriate salary for the Executive Director of a national professional association with over $3 million in annual revenue.

That, on its own, might not raise eyebrows.

Unlike NCRA, the Illinois Court Reporters Association (ILCRA) does not publicly disclose what it pays Wenhold or his firm. ILCRA is a smaller, state-level nonprofit, and although it is subject to similar nonprofit regulations, it has not published any Form 990s with salary details easily accessible to members or the public.

This lack of transparency leaves key questions unanswered:

Without clear disclosure, the overlap of compensation and roles becomes not only unusual—but also potentially unprecedented in this industry.

We know from public records that Dave Wenhold earns over $300,000 per year from NCRA alone. When estimating his total compensation, we must also account for his roles in ILCRA and numerous other associations managed under his firms, including Kautter Wenhold and Miller Wenhold Association Management.

If he receives even modest compensation—say, $30,000–$60,000 per year—from each of 8 to 12 additional associations, his total annual earnings could range from $500,000 to over $1 million. This would place him among the highest-paid association executives in the nonprofit space.

Beyond earnings, such an arrangement raises serious governance questions:

At this level of income and influence, the profession must demand transparency, rigorous oversight, and clear separation of responsibilities.

In most nonprofit sectors, especially among larger, fully funded organizations, it is not standard for an Executive Director to hold multiple concurrent paid executive roles, particularly within related fields. It’s one thing to be a part-time executive for a small, local group; it’s another to be the full-time, six-figure-paid leader of a national association while simultaneously leading a state affiliate and others.

Best practices, as outlined by governance watchdogs like BoardSource, emphasize:

This concentration of influence, decision-making authority, and potentially duplicated compensation is not typical—and certainly not transparent.

Adding to the concern, the NCRA has seen a steady decline in membership under Wenhold’s leadership. The profession itself is under siege, yet the national organization tasked with defending it appears to be shrinking in size, budget, and impact.

Meanwhile, NCRA has been criticized for failing to take a strong enough stance against digital reporting—a growing threat to the profession. Perhaps most troubling is NCRA’s lack of visibility and involvement in major legislative efforts in California, which has the largest court reporting population in the country.

If the national association isn’t showing up in the most critical legislative battles, and its membership and visibility are declining, then what exactly are members paying for?

This issue should spark serious reflection within the court reporting community:

In many other professions, this kind of overlap would be viewed as a governance risk—something to fix, not normalize.

Here’s a roadmap for reform:

This conversation isn’t personal—it’s principled. Dave Wenhold may be a capable executive. But the issue isn’t whether he can handle the work. It’s whether the structure itself serves the best interests of the profession.

A thriving, credible court reporting field depends on balanced leadership, clear boundaries, and true member representation. If we let convenience override fairness, or familiarity override scrutiny, we undermine the very trust that keeps our associations strong.

It’s time to take a hard look at how power is distributed in our profession—and to make sure every court reporter in every state gets a fair seat at the table.

Leadership must reflect the values of the profession it serves—accuracy, impartiality, integrity. That applies as much to how our associations are run as it does to how our transcripts are produced.

One person can’t be everywhere. One firm shouldn’t be at the center of everything. The appearance of control, influence, or favoritism—even if unintended—is enough to warrant review.

Members deserve assurance that their associations are being run with focus, fairness, and fidelity to their mission. And when one person or firm holds a dozen titles across overlapping organizations, that assurance becomes harder to provide.

The content of this post is intended for informational and discussion purposes only. All opinions expressed herein are those of the author and are based on publicly available information, industry standards, and good-faith concerns about nonprofit governance and professional ethics. No part of this article is intended to defame, accuse, or misrepresent any individual or organization. Readers are encouraged to verify facts independently and to engage constructively in dialogue about leadership, transparency, and accountability in the court reporting profession.

***To unsubscribe, just smash that UNSUBSCRIBE button below — yes, the one that’s universally glued to the bottom of every newsletter ever created. It’s basically the “Exit” sign of the email world. You can’t miss it. It looks like this (brace yourself for the excitement):

The content on this blog represents the personal opinions, observations, and commentary of the author. It is intended for editorial and journalistic purposes and is protected under the First Amendment of the United States Constitution.

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

A respectful reply to a comment submitted in support of the entity known as Steno In The City‘s (registered trademark) event partnership with ILCRA

*”Since this blog is labeled as a safe space, let me ask, could there possibly be a different perspective to consider in regard to the scrutiny of this matter? For example, many non-profits contract with private businesses in order to throw events and such for social networking opportunities. When I looked at the posts it is clear that the $75 ticket is going directly towards the food, drinks and access to the venue. Just because ILCRA is a non-profit does not entitle them to use any event space for free. Food and drinks also come with a price tag. The event is in no way marketed as a fundraising event, nor does it suggest that funds will be distributed to any specific cause other than providing a space and food/drinks to those who voluntarily purchase a ticket.

I do not believe that ILCRA allowing SITC to help organize a social gathering is illicit. The work SITC has done to promote the court reporting industry is invaluable, and their events are notoriously upscale and high quality. Maybe ILCRA wants to partner with an org that has the same goals, which is to advance the industry of court reporting. Sometimes it’s okay to let things be fun. We don’t have to put a magnifying glass on everything, especially not a cocktail party.”*

Thank you for the comment — you raise points that many people might also be wondering, and it’s important that this conversation happens in a transparent and respectful way. So let’s take a closer look at the assumptions here and break down why this is not just “a fun social event” but a partnership that raises serious legal, financial, ethical, and data privacy concerns.

Let’s walk through this point by point, clearly and without judgment:

🔴 WHAT’S WRONG:

You’re absolutely right — nonprofits do contract with caterers, venues, and vendors. But that’s not what’s happening here.

This isn’t just about ILCRA paying a vendor. In this case:

This is not a standard vendor relationship — this is a joint branding and financial arrangement with a private entity. That’s legally and ethically different from hiring a caterer.

🔴 WHAT’S WRONG:

Even if that’s true — that doesn’t justify sending money and data through a private business without transparency, oversight, or board authorization.

Unless:

Then ILCRA cannot claim this is a simple cost-recovery event. It may actually violate:

Even for a cocktail party, nonprofits must account for every dollar collected in their name.

🔴 WHAT’S WRONG:

The issue isn’t whether this is labeled a fundraiser — the issue is where the money goes and how it’s handled.

Then ILCRA is opening itself up to questions about misuse of its name, lack of board supervision, and possible inurement violations.

Fundraising or not — if money is being collected under the ILCRA brand, members deserve transparency.

🔴 WHAT’S WRONG:

Even if past events were enjoyable, reputation and aesthetics do not exempt anyone from scrutiny.

The concern is that:

This is not about whether an event looks upscale — it’s about whether ILCRA should legitimize a partnership with someone facing serious and unresolved legal allegations.

🔴 WHAT’S WRONG:

This is the most dangerous assumption of all.

Even a cocktail party becomes serious when:

Professional associations must scrutinize every public-facing activity — especially ones involving finances, branding, and member trust.

Calling it “just a social event” doesn’t make the risk go away.

While the event may be described as a simple social gathering, it’s important to consider the broader legal context involving the individual co-hosting and facilitating the event.

In addition to the pending COPE complaint filed with the NCRA, there are active and documented investigations into the actions of SITC’s founder by multiple agencies:

These investigations are not speculative or anecdotal. They are based on formal complaints, documented communication with agencies, and direct confirmations. The existence of these ongoing inquiries underscores why ILCRA — as a professional nonprofit bound by fiduciary duty — should be exercising extreme caution before associating its name, membership, and data infrastructure with this individual or her organization.

All of the allegations outlined herein are based on Shaunise Day’s own public admissions and documented activity across her social media platforms, where she has personally posted evidence of the events, practices, and representations in question.

In March 2025, a formal and confidential complaint was submitted to NCRA through the COPE process. That complaint included detailed allegations and supporting documentation of the above-listed allegations and investigations. NCRA Executive Director Dave Wenhold was directly informed of these matters at that time in his NCRA leadership capacities, and at the time, he was also the ILCRA Executive Director.

At no point was confirmation given that these concerns would be escalated to ILCRA leadership — and to be clear, COPE matters are confidential. However, given that Mr. Wenhold was fully informed of the nature and scope of the allegations in March 2025, he was in a position to ethically and prudently advise against any formal partnership with the subject of the complaint while serious legal and ethical concerns remained unresolved.