Judge Tells Attorneys They Don’t Need a Court Reporter for Trial — Even When Certified Reporter is Present and Assigned

Legal Experts Warn of Due Process Violations, Inflated Statistics, and a Strategic Power Grab to Eliminate Human Reporters

“I was in the courtroom when it happened: A judge told attorneys they didn’t need a court reporter for thier trial— even though one was there, ready to work.”

LOS ANGELES — On July 28, 2025, in Department 5 at the Spring Street Courthouse (SSC), Judge Karlan Shaller told attorneys preparing for an unlimited civil trial that they “don’t need a court reporter” — despite being informed that a certified shorthand reporter had been assigned to their entire trial and was present in the courtroom, ready to work.

Although the trial ultimately proceeded with a reporter, the judge’s statement raised deeper concerns — not about whether the record would be preserved by electronic means, but whether the court’s entire strategy had been in bad faith from the beginning. Long before SB 662 was formally defeated, the court had invested heavily in electronic recording infrastructure, confident the bill would pass. When it didn’t, Jessner’s workaround order provided a backdoor — and now, judges are acting as though the law has already changed, normalizing the elimination of human reporters to lay the groundwork for making that legal reality permanent.

Months earlier, in Department 30 at Stanley Mosk Courthouse, presided over by Judge Barbara Scheper, an unlimited civil trial proceeded without a reporter — even though one was present and available. That proceeding now has no official transcript, despite a clear legal requirement under California Code of Civil Procedure § 269 and Rule 2.956.

Court observers say these are not isolated incidents. They are part of a larger, coordinated shift — one that isn’t about staffing shortages or courtroom efficiency.

It’s about power and profit.

“They don’t even want a record anymore — because now they own it.”

— Veteran Court Reporter

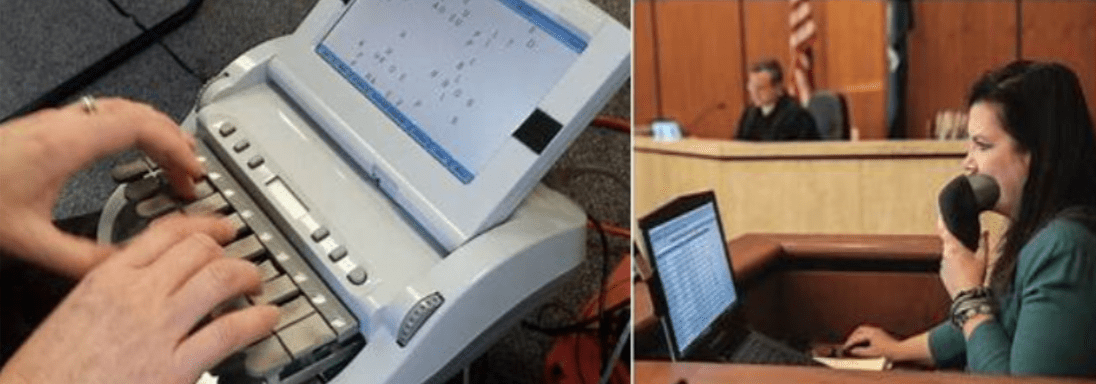

California Law Requires Reporters — When Available

California’s governing laws and court rules are unambiguous:

- CCP § 269(a): Requires certified shorthand reporters to record all trial proceedings in unlimited civil matters.

- Rule 2.956: Prohibits audio recording in such cases unless expressly permitted — and only when no certified reporter is available.

- Rule 5.532: Mandates transcripts upon request, prepared and certified by licensed reporters.

When a certified court reporter is present and available, the law requires their use. Judges are not authorized to disregard that requirement or suggest that a transcript is optional.

Presiding Judge Jessner’s General Order – What It Did

On September 5, 2024, then-Presiding Judge Samantha P. Jessner of the Los Angeles County Superior Court issued a general order allowing the use of electronic recording devices in family law, probate, and unlimited civil proceedings — but only when no court-employed or privately retained court reporter was available.

In the order, Jessner claimed that the prohibition against recording in these case types discriminated against low-income litigants, stating:

“Where such fundamental rights and liberty interests are at stake, the denial of [electronic recording] to litigants who cannot reasonably secure a [court reporter] violates the constitutions of the United States and the State of California.”

She called the law “legislative discrimination” and claimed it failed to meet any compelling interest.

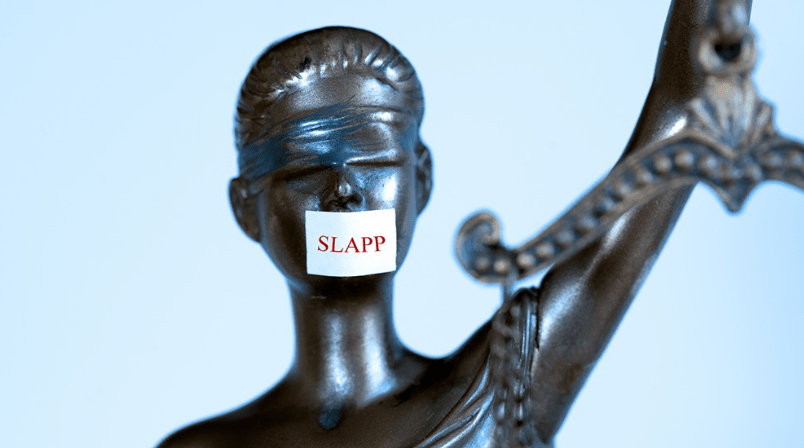

Critics — including the California Court Reporters Association (CCRA), labor unions, and legal watchdogs — immediately condemned the order as an illegal overreach and a violation of state law. They argue Jessner was effectively legislating from the bench, creating policy that the California Legislature had explicitly rejected.

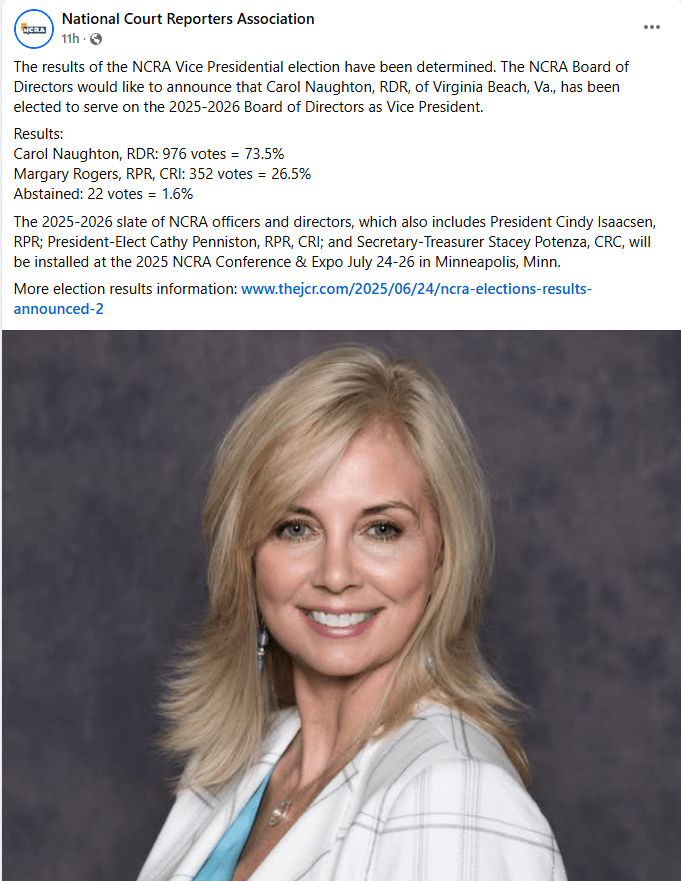

The “1.7 Million Unreported Hearings” Narrative

To justify the expansion of electronic recording, court officials have repeatedly cited a staggering figure: more than 1.7 million civil, family, and probate hearings statewide lacked a verbatim record over just two years.

But legal analysts and court insiders say this figure is deeply misleading.

Many of those “unreported” hearings are routine calendar matters — scheduling conferences, status updates, continuances — not full evidentiary hearings or trials. These are events that rarely result in transcript requests or appellate issues.

By padding the data with low-level, non-substantive events, the court has crafted a self-serving narrative to make it appear as though critical proceedings are being lost — when in fact, the vast majority were never the kinds of proceedings where transcripts are traditionally ordered.

“This isn’t about 1.7 million missed trials,” said one legal policy expert. “It’s about inflating numbers to push a predetermined agenda — displacing human reporters and centralizing control of the record.”

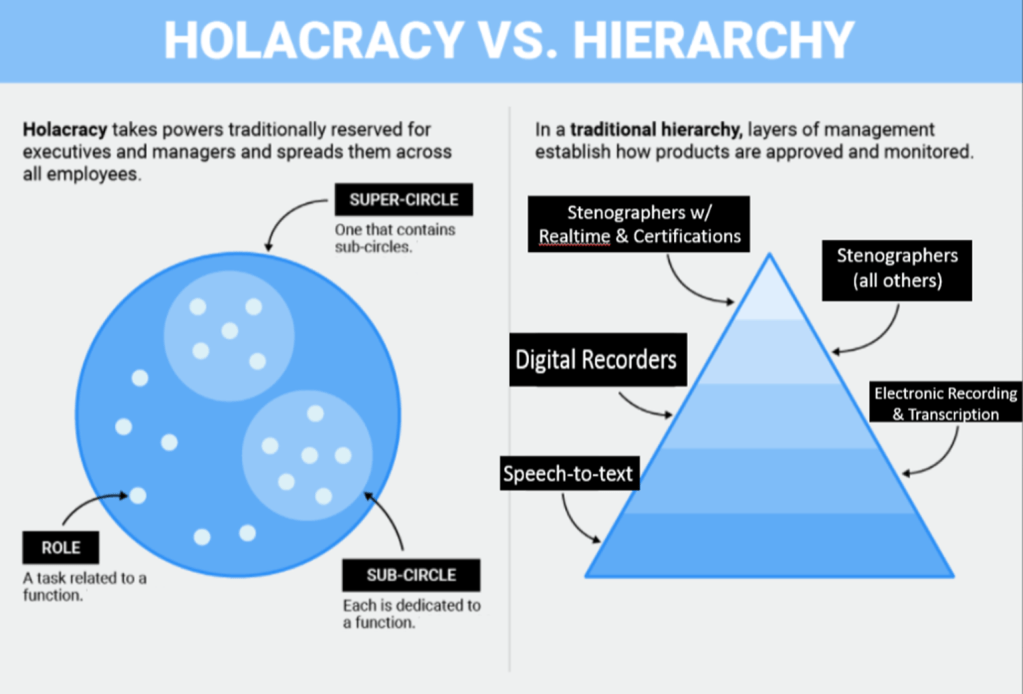

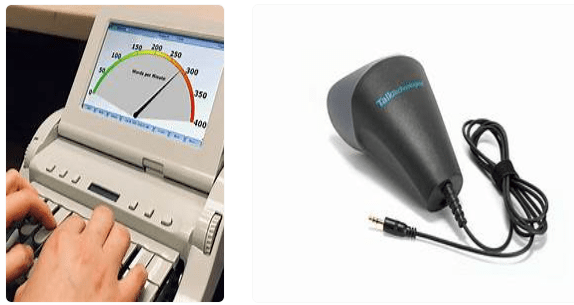

Behind the Push – Control, Monetization, and Elimination

This is not just about modernization — it’s about control of the record.

When the court owns the audio, it owns the record. It can:

- Sell transcripts directly to litigants and attorneys.

- Restrict or delay access to sensitive or unflattering content.

- Eliminate independent oversight that certified reporters once provided.

- Replace ethical, licensed professionals with unregulated contractors or AI.

“They’re not treating the record as optional,” said one veteran court reporter. “They want to own it, monetize it, and weaponize it. That’s why they want us gone.”

Unlike certified shorthand reporters — neutral officers of the court subject to licensing and ethical standards — machine-generated transcripts and digital files are fully controlled by the court itself. This removes one of the last independent checks inside the courtroom.

It’s not just a power shift.

It’s a power grab.

Jessner’s Order Was A Ruse, Not a Remedy

Presiding Judge Samantha P. Jessner publicly framed her September 2024 general order as a compassionate, temporary workaround for under-resourced departments during the court reporter shortage. But critics say that explanation was a calculated misdirection — and that the order was never designed to be a stopgap.

“Jessner’s order was a ruse,” said a senior court reporter. “It was a deliberate step in a long-term strategy to displace us entirely.”

Although the order’s language limited electronic recording to situations where no reporter was available, it created a culture where judges now behave as if certified reporters are optional — even when they are present, assigned, and ready to work.

That’s exactly what happened in Mosk Department 30, where the court proceeded without a reporter despite one being in the room — and nearly happened in SSC Department 5.

Since the day the order was issued, judges across Los Angeles County have increasingly sidelined reporters in favor of audio recordings or no record at all. One such instance occurred on July 28, 2025, when a judge told attorneys in open court that they don’t even need a reporter anymore — despite one being assigned and available.

Justice Without a Record

When courts bypass certified reporters:

- There’s no transcript. No appeal.

- No accountability for misconduct or improper rulings.

- No transparency for the public.

In Mosk Department 30, the result is a trial with no record, no transcript, and no meaningful route for review. That’s not efficiency. That’s erasure.

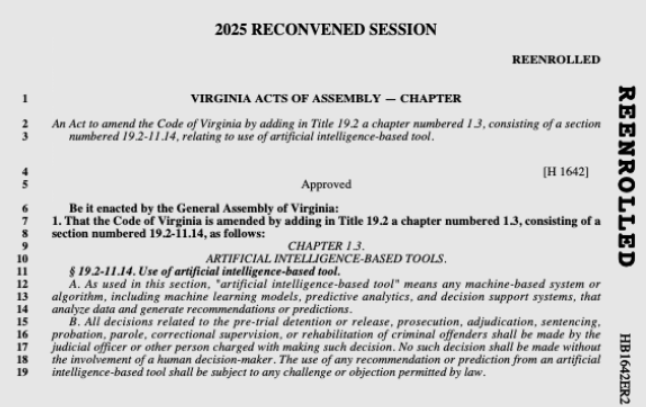

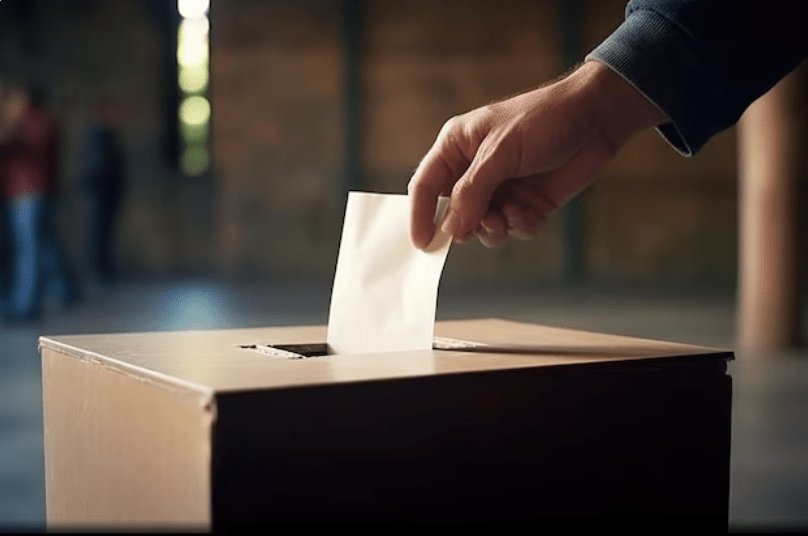

Legislative Defeat of SB 662 and the Judicial Workaround

In early 2024, California lawmakers considered Senate Bill 662, introduced by Senator Susan Rubio, which would have authorized electronic recording in all civil proceedings, including unlimited civil and family law cases.

The bill would have:

- Allowed digital recording even when no reporter was present;

- Required courts to attempt to hire a reporter first;

- Given certified reporters the right of first refusal to transcribe;

- Paved the way for expanded AI transcription in trial courts.

The bill faced fierce opposition from court reporters, labor unions, and access-to-justice groups who warned of errors, reduced oversight, and unfair appeal outcomes.

In January 2024, SB 662 was quietly defeated in the Senate Appropriations Committee, never reaching the Senate floor.

But the defeat didn’t stop the judiciary. Just eight months later, Jessner issued her general order, implementing the very policies the Legislature had rejected — without a public vote or legislative authority.

“SB 662 died in committee. Jessner brought it back to life — with a stroke of the pen,” said one former legislative consultant.

🗓️ Timeline: SB 662 and the Judiciary’s Workaround

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| Feb 16, 2023 | SB 662 introduced by Sen. Susan Rubio |

| May 2023 | Bill passes Senate Judiciary Committee |

| Jan 2024 | Bill dies in Senate Appropriations Committee |

| Sept 5, 2024 | Judge Jessner issues general order allowing ER in civil courts |

| Sept 2024 onward | Judges begin bypassing certified reporters — even when present and assigned |

| Jan 1, 2025 | Jessner’s term as Presiding Judge ends; succeeded by Judge Sergio Tapia |

This Isn’t Negligence. It’s a Strategy.

What’s happening in Departments 5 and 30 isn’t a mistake or miscommunication. It’s a coordinated dismantling of independent court reporting — to consolidate power, control the record, and convert public justice into a revenue stream.

The courts are no longer treating the record as optional.

They’re treating it as merchandise.

It’s time the legal community, lawmakers, and the public say no.

Say no to inflated statistics.

Say no to judicial workarounds.

Say no to trials with no record and no recourse.

Justice must be recorded. And the record must belong to the people — not the system.

What Can Court Reporters Do?

Reporters must stay vigilant. When at courthouses, look into departments, check calendars, and verify whether trials are being held with a certified reporter present.

- If you see an unlimited civil trial proceeding without a reporter, document what you observed: the department number, judge’s name, date, and whether parties or jurors were present.

- Politely ask courtroom staff or attorneys if a reporter has been assigned.

- If you’re available to report and not being utilized, make it known — preferably in writing or on the record.

- Report the incident to your professional association (like CCRA), the local union, or legal advocacy groups monitoring compliance.

- Currently, there are no formal legal advocacy groups publicly announced as monitoring compliance with Jessner’s order or California court reporter laws on a systemic level.

- However, informal monitoring is taking place through:

- California Court Reporters Association (CCRA)

- Los Angeles County Court Reporters Association (LACCRA)

- Individual reporters and watchdogs

- Whistleblower-led documentation efforts, such as those discussed in this article

This quiet erosion of rights thrives in silence. It’s time to raise our voices — and document everything.

Because when there’s no record, there’s no justice.

Other articles on the subject of AB 662:

Judges in Los Angeles County are Breaking the Law!

StenoImperium

Court Reporting. Unfiltered. Unafraid.

Disclaimer

“This article includes analysis and commentary based on observed events, public records, and legal statutes.”

The content of this post is intended for informational and discussion purposes only. All opinions expressed herein are those of the author and are based on publicly available information, industry standards, and good-faith concerns about nonprofit governance and professional ethics. No part of this article is intended to defame, accuse, or misrepresent any individual or organization. Readers are encouraged to verify facts independently and to engage constructively in dialogue about leadership, transparency, and accountability in the court reporting profession.

- The content on this blog represents the personal opinions, observations, and commentary of the author. It is intended for editorial and journalistic purposes and is protected under the First Amendment of the United States Constitution.

- Nothing here constitutes legal advice. Readers are encouraged to review the facts and form independent conclusions.

***To unsubscribe, just smash that UNSUBSCRIBE button below — yes, the one that’s universally glued to the bottom of every newsletter ever created. It’s basically the “Exit” sign of the email world. You can’t miss it. It looks like this (brace yourself for the excitement):

You must be logged in to post a comment.