There are moments in history when incrementalism is a death sentence. When polite silence is complicity. When waiting for permission is the same as surrendering the field.

The court reporting profession is in exactly that moment right now.

For too long, we’ve operated under a culture of politeness, deference, and “not rocking the boat.” We’ve tolerated leaders who built their reputations, careers, and bank accounts under an old order — one that rewarded complacency, not courage. We’ve tiptoed around hard conversations, let agencies set the narrative, and watched regulators be captured by the very interests they’re supposed to oversee.

That era ends now.

We are at war for the future of this profession. And wars are not won by committees, caution, or courtesy. Wars are won by clarity, courage, and leadership willing to do what others won’t.

The Culture That Got Us Here Can’t Get Us Out

One of the most powerful lines I’ve ever heard is this: “It’s hard to change a culture with people who benefited from that previous culture.”

Let that sink in.

The current status quo — the same associations, boards, and entrenched players who oversaw the rise of digital recording, the notary loophole, and the quiet erosion of stenographic dominance — cannot be the ones we trust to lead us out of this. They built this house. They profited while it burned.

They were at the table when digital firms maneuvered around licensing rules. They nodded while state boards let AI transcription products creep in under “pilot programs.” They remained silent when agencies started assigning “responsible charge” titles to reporters who never even touched the audio.

And when reporters finally began to push back, what did these leaders do? Most deflected. Some gaslit. Others smiled and told us to “work together.”

No more.

We need new leaders who are not beholden to the structures that failed us. We need leadership that isn’t afraid to challenge agency money, confront regulatory capture, and defend our license and our role as guardians of the record.

No More Soft Leadership

This profession has, for too long, confused kindness with weakness. We’ve allowed fear — of losing work, of being blacklisted, of being “divisive” — to muzzle truth.

Meanwhile, digital recording companies have moved like special forces: coordinated, well-funded, strategic. Their lobbyists have walked into statehouses while we were too busy arguing over association titles and bylaws. Their technology teams have pitched their products to judges and legislators while too many of our leaders were still debating whether to send a sternly worded letter.

It’s not enough to “raise awareness.” It’s not enough to host luncheons. It’s not enough to pat ourselves on the back for issuing a press release two months too late.

We need a wartime mindset. We need leaders who will call out regulatory malpractice when they see it. We need associations that act like special operations teams, not garden clubs. We need reporters willing to be loud, strategic, disciplined, and unflinching.

Leadership Matters — And So Does Accountability

When the notary loophole was quietly opened in California, enabling digital recording firms to bypass reporter licensing laws, Cheryl Haab was president of the DRA. That is not conjecture — it is fact. Her leadership coincided with a critical turning point for the profession, one that fundamentally altered the legal terrain for stenographers statewide.

Years later, when I publicly began holding her accountable for that failure in Facebook groups, she did not engage with the substance of my criticism. Instead, she launched a sustained personal campaign to discredit me — gaslighting, shifting blame to others, spreading falsehoods to turn colleagues against me, and publicly threatening me with “cancel culture” while calling me a “snake in the grass” and a liar.

This isn’t just a personal dispute; it’s emblematic of a leadership culture that punishes whistleblowers, instead of confronting its own history. Rather than acknowledging the strategic failures that helped usher in the current crisis, the old guard resorts to character attacks, and gatekeeping to silence dissent. Based on my direct experiences and documented communications, I believe she engaged in a sustained effort to discredit me and silence my criticism. Behind the scenes, she engaged in whisper campaigns, professional isolation, and intimidation designed to make me back down and silence my criticism. This is a real-world example of how leadership power is weaponized socially to discourage dissent. That’s not leadership. That’s intimidation, plain and simple — wielded to silence dissent and shield themselves from accountability.

True leadership demands accountability, not cancel culture. It requires humility about past decisions and the courage to support new strategies — not personal attacks on those who challenge entrenched power.

National Leadership Vacuum

While state-level missteps like the notary loophole opened the door for digital encroachment, the National Court Reporters Association (NCRA) has failed to step into the role of a true national leader. At a time when the profession desperately needs unified strategy, aggressive lobbying, and public education campaigns, the NCRA has largely retreated into the role of a CEU vendor — focused on selling seminars, certifications, and convention tickets, rather than leading a coordinated national defense of the profession.

Instead of setting the agenda and marshaling resources to confront legislative threats, regulatory capture, and the rapid expansion of AI transcription, NCRA has behaved more like a trade show operator than a strategic command center. Reporters look to their national organization for bold leadership, but what they get are webinars and continuing education credits — a transactional relationship, not a visionary one.

This failure has been so profound that an outsider — not even a licensed reporter — was able to infiltrate the profession simply by volunteering at a few NCRA conventions, then positioning herself as someone who could offer “better,” more glamorous events. Rather than upholding their own standards, NCRA bent its own CEU rules to grant her credit approvals, despite the fact that she does not meet the published qualifications required for CEU presenters or providers.

When the national association responsible for safeguarding standards starts lowering the bar for opportunists while ignoring its strategic role, it signals a dangerous leadership void. This is not just negligence — it’s how industries get co-opted. NCRA’s unwillingness to hold the line has created space for outsiders to shape the narrative, monetize the profession, and position themselves as leaders in the absence of real ones.

This vacuum at the top has opened the door for agencies, tech companies, and opportunistic lobbyists to control the narrative state by state, advancing their interests while NCRA passively observes from the sidelines. In the absence of strong national leadership, others have filled the void — writing the laws, shaping policy conversations, and courting the judiciary, often with little to no pushback from the very organization that should be leading that charge.

In a time of existential threat, selling CEUs is not leadership. Leadership is setting the agenda, not reacting to it. It’s anticipating threats, not playing catch-up years later. It’s mobilizing the profession, defending the record, and shaping the legislative and cultural landscape with authority and vision. NCRA’s failure to do so has left reporters scattered, agencies emboldened, and policymakers misinformed — a dangerous mix in a time when the survival of our profession depends on unified, strategic action.

Raise the Standards — For Everyone

Part of the problem is internal. Let’s be honest: our standards have slipped.

There are reporters who’ve become complacent, who rely on agencies to spoon-feed them jobs and then gripe about rates without ever learning to negotiate. There are associations that exist more to protect board seats than to protect the profession. There are committees that spend more time planning cocktail hours than legislative campaigns.

If we are to win this war, we must hold ourselves to a higher standard — individually and collectively.

- Professionalism must be non-negotiable. That means showing up sharp, prepared, tech-competent, and ready to own the record.

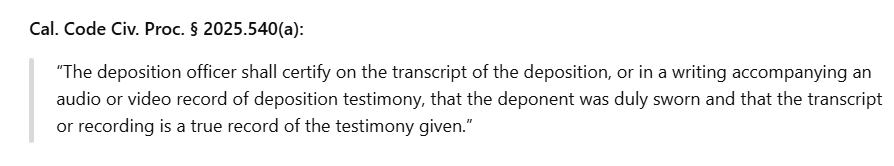

- Advocacy must become part of the job, not a side hobby. If you don’t know your state’s relevant statutes, if you can’t articulate why digital reporting fails due-process standards, then you’re unprepared for the battle we’re in.

- Leadership roles must be earned through performance, not tenure or popularity. If you’ve sat on a board and presided over decline, step aside. If you want to lead, show results, not résumés.

The truth is simple: either we’re ready to win, or we’re not. There is no middle ground.

Clear Out the Deadwood

It’s time to challenge and, if necessary, oust leaders who are unwilling to adapt. That means hard conversations. That means voting differently. That means refusing to support organizations that have proven unwilling to fight.

Some people will say, “But that sounds divisive.”

You know what’s more divisive? Watching the profession split in two — half under agencies using uncertified digital recorders and half clinging to the idea that “it will all work out.”

The only way to rebuild a strong, unified culture is to clear out the deadwood. We cannot build a winning strategy on a foundation of compromise and cowardice.

No More Excuses

Every time a reporter says, “Well, that’s just how it is now,” the digital firms win. Every time an association says, “We can’t afford to make waves,” the agencies win. Every time a board member says, “Our hands are tied,” the regulators win.

This is not a time for excuses.

This is a time for strategy, accountability, and courage.

- Agencies exploiting the notary loophole? Expose it publicly and file complaints.

- Boards captured by ASR lobbyists? Demand resignations and replacements.

- Associations asleep at the wheel? Mobilize members to vote them out.

- Reporters sitting on the sidelines? Recruit them, educate them, light the fire.

We either lead this fight, or we watch it happen without us.

A New Ethos – The Guardian’s Mindset

Court reporters are not stenographers for hire. We are guardians of the record. We are officers of the court. We are the last line of defense between justice and chaos.

Our mindset must reflect that.

That means discipline. That means moral courage. That means calling out unethical behavior even when it’s uncomfortable. That means showing up in legislative chambers and courtrooms not as supplicants, but as professionals with authority and knowledge.

We cannot afford to play defense anymore. We must seize the initiative — in law, in technology, in culture.

The Call

If reading this makes your heart sink because you prefer the old comfort of silence, step aside.

If this fires you up — good. That’s the beginning of a movement.

The future of this profession will not be decided by agencies, regulators, or tech companies. It will be decided by reporters who refuse to accept decline as destiny.

This is not a time for soft leadership. This is not a time for nostalgia. This is a time to man up, gear up, and speak up.

The warrior ethos of our profession isn’t about bravado. It’s about discipline, clarity, and courage in the face of overwhelming odds.

History will remember whether we stood our ground or surrendered politely.

The choice is ours.

StenoImperium

Court Reporting. Unfiltered. Unafraid.

Disclaimer

This article reflects my perspective and analysis as a court reporter and eyewitness. It is not legal advice, nor is it intended to substitute for the advice of an attorney.

This article includes analysis and commentary based on observed events, public records, and legal statutes.

The content of this post is intended for informational and discussion purposes only. All opinions expressed herein are those of the author and are based on publicly available information, industry standards, and good-faith concerns about nonprofit governance and professional ethics. No part of this article is intended to defame, accuse, or misrepresent any individual or organization. Readers are encouraged to verify facts independently and to engage constructively in dialogue about leadership, transparency, and accountability in the court reporting profession.

- The content on this blog represents the personal opinions, observations, and commentary of the author. It is intended for editorial and journalistic purposes and is protected under the First Amendment of the United States Constitution.

- Nothing here constitutes legal advice. Readers are encouraged to review the facts and form independent conclusions.

***To unsubscribe, just smash that UNSUBSCRIBE button below — yes, the one that’s universally glued to the bottom of every newsletter ever created. It’s basically the “Exit” sign of the email world. You can’t miss it. It looks like this (brace yourself for the excitement):

You must be logged in to post a comment.