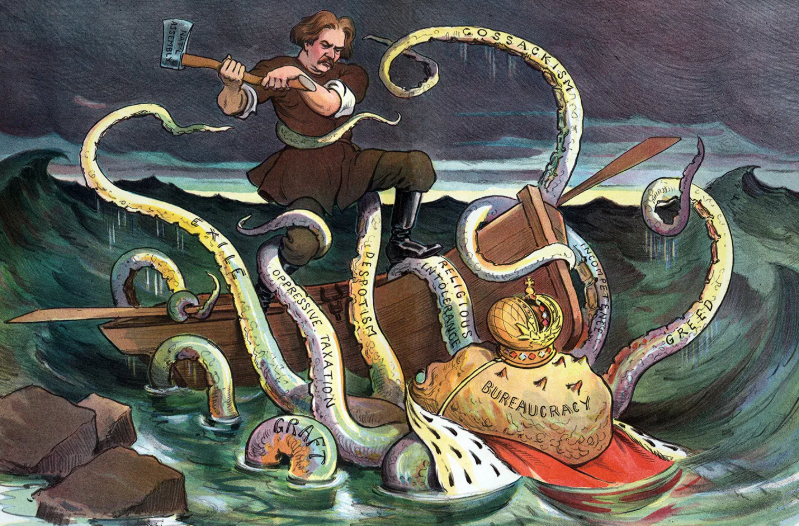

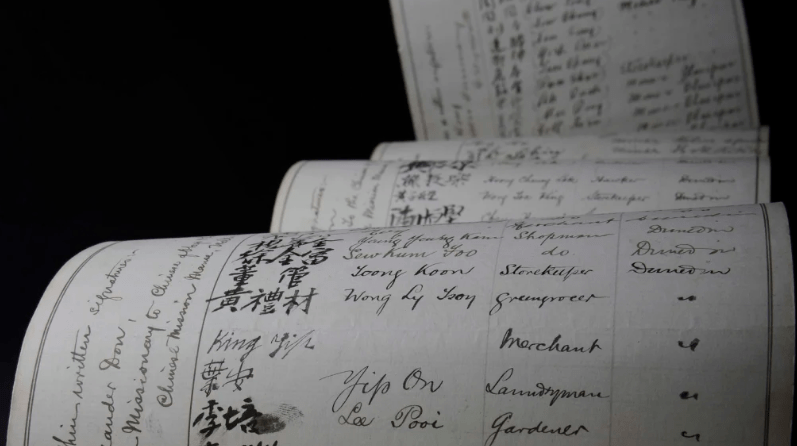

When a Texas personal injury attorney recently posted his deposition invoice on LinkedIn, the reaction was immediate and visceral. An $858 charge for a physical transcript he said he never requested. A separate fee for a condensed version. Nearly $180 to bind exhibits into a paper copy he did not want. Fifty dollars for a digital file. Another fifty for something called “processing and compliance.” His conclusion was blunt: greed has entered court reporting, private equity is to blame, and someone is squeezing lawyers dry.

The frustration is understandable. Few professionals like discovering unexpected charges on a bill, particularly when they believe they asked for something simple: a PDF. But what this invoice reveals is not a profession suddenly becoming predatory. It reveals an industry that has been structurally transformed, where the people creating the record are no longer the ones setting the prices, and where attorneys are increasingly paying corporate markups that never reach the court reporters whose names appear on the cover page.

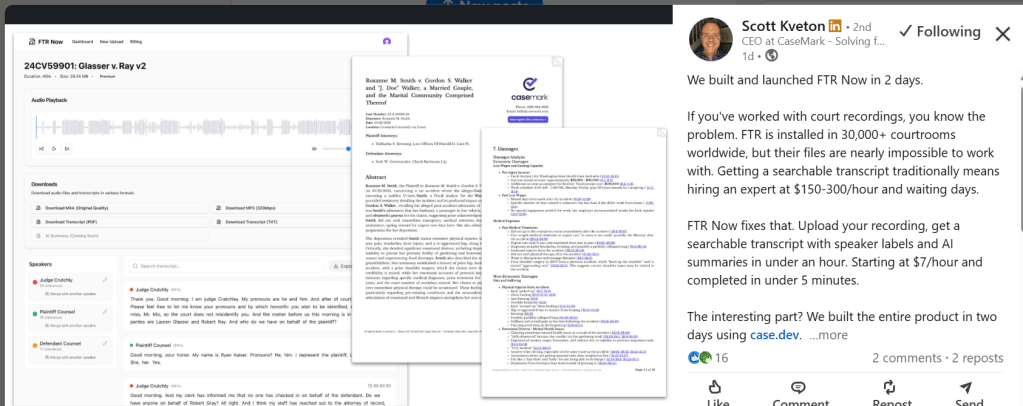

The modern court reporting marketplace is no longer dominated by independent professionals and small local agencies. Over the last decade, large national firms backed by private equity have consolidated significant portions of the litigation support market. These companies control scheduling platforms, preferred-vendor lists, national contracts, and billing infrastructure. They market themselves as technology companies. They present as logistics providers. They are increasingly owned by investment groups whose fiduciary obligation is not to the justice system, but to growth curves and exit strategies.

That distinction matters, because the reporter who took down every word of the proceeding does not control whether a physical transcript is automatically produced, whether exhibits are bundled into a paper volume, whether “compliance” appears as a line item, or whether a digital file is sold as a premium product. Those decisions are made upstream, by billing departments far removed from the deposition room.

It also matters because, despite rising end-user prices, working court reporters are earning less, not more.

Across the country, reporters who once received a majority share of transcript revenue now routinely report that they receive as little as 30 to 50 percent of what agencies ultimately bill. The rest goes to overhead, sales operations, platform fees, administrative layers, investor returns, and acquisition debt. While invoices climb, per-page compensation has stagnated or declined. Many reporters today are paid rates that would have been considered unacceptable twenty years ago, even as production expectations, turnaround times, and technological burdens have increased.

This is the uncomfortable truth rarely reflected in online outrage: when attorneys are charged hundreds or thousands of dollars, it does not mean the reporter was paid hundreds or thousands of dollars. Often, it means the reporter was paid a fraction of that amount, long after the agency collected the full fee.

In California, where transcript pricing for official court proceedings is governed by statute, the contrast is particularly stark. State law sets per-word rates for originals and copies. It contemplates transparency, uniformity, and public accountability. It reflects an understanding that the legal record is not a luxury good. It is a foundational component of due process.

But the private deposition marketplace now operates largely outside that regulated framework. Rates are no longer tethered to the labor of producing a record. They are bundled into packages. They are layered with service fees. They are detached from the statutory logic that once anchored the profession.

This shift has produced confusion for attorneys and moral injury for reporters.

Lawyers see invoices that appear arbitrary. Reporters see clients angry at them for decisions they did not make. The result is a growing misdirection of blame. Frustration that should be aimed at corporate pricing models lands instead on individual professionals, many of whom are struggling to remain in a field that is losing experienced practitioners at an alarming rate.

The attorney who posted his bill emphasized that he had “nothing against court reporters.” Yet the public framing still implied that court reporting itself has become exploitative. That framing, repeated often enough, becomes dangerous. It erodes trust in the very people whose role is to preserve the integrity of proceedings. It obscures the fact that many reporters today feel trapped between clients who are angry about prices and agencies that dictate terms they cannot negotiate.

There is another dimension to this problem that deserves attention: automatic fulfillment.

In many large corporate systems, default transcript production is built into workflows. Paper copies are generated unless specifically blocked. Exhibit processing is standardized. Condensed versions, litigation packages, and archival services are preloaded into billing templates. These systems are efficient for scale. They are not designed for nuance.

Efficiency is not the same as consent.

When a lawyer says, “I’ll take a digital copy,” that statement passes through scheduling software, production queues, quality-control departments, and outsourced billing operations. At each stage, default settings can override intent. What emerges on the invoice may reflect corporate protocol more than client request.

That is not a reporting problem. It is a business-model problem.

Private equity does not invest in industries to preserve tradition. It invests to extract margin. That often means increasing volume, expanding services, cross-selling products, and monetizing every stage of a workflow. In court reporting, that workflow includes the legal record itself. The transcript becomes not just a document, but a revenue platform.

This transformation has consequences. It changes how services are packaged. It changes how reporters are compensated. It changes how clients experience what was once a straightforward professional exchange.

And it carries a risk that should concern every litigator: when the legal record is treated primarily as a monetizable asset, rather than a neutral civic function, incentives shift. Speed pressures increase. Labor is commoditized. Experienced reporters leave. Shortages grow. Courts experiment with alternatives. The very infrastructure of reliable record-making begins to weaken.

Against that backdrop, the solution is not to publicly shame a profession already under strain. It is to reconsider where legal work is being sourced.

Local and independent reporting firms still exist. Many are owned by working reporters. Many operate with transparent rate sheets, direct communication, and client-specific orders. In those environments, when an attorney asks for a PDF, that is what is produced. When a question arises about cost, the person answering it is often the same person who created the record.

Choosing those providers is not nostalgia. It is a market decision.

Every deposition scheduled through a national consolidation firm reinforces the very pricing structures attorneys say they oppose. Every exclusive contract awarded to a private-equity-backed provider accelerates the displacement of independent operators. Every complaint aimed at “court reporters” rather than corporate intermediaries misidentifies the source of the problem.

There is a deeper irony here. Lawyers, of all professionals, understand the difference between the individual and the institution. They argue every day that systems, incentives, and structures matter. Yet when it comes to court reporting, the narrative often collapses into a single figure in the room, when in reality the power has long since moved elsewhere.

If attorneys want fewer surprise charges, they should ask who controls the billing. If they want ethical alignment, they should ask who owns the company. If they want sustainability, they should ask whether the people creating the record can afford to remain in the profession.

And if they want to stop private equity from reshaping the legal services ecosystem, they should stop feeding it.

Court reporters are not getting rich off inflated invoices. Many are leaving because they cannot make a living wage from the work that once sustained them. The real question raised by that LinkedIn post is not, “How much should a PDF cost?” It is, “Who is building a business model on top of the legal record, and at whose expense?”

Until that question is answered honestly, outrage will continue to land in the wrong place, and the people most essential to the justice system will continue to pay for decisions they did not make.

Disclaimer

This article reflects the author’s professional observations, industry research, and firsthand experience as a working court reporter. It is commentary and analysis, not legal advice. Company practices and billing structures vary. Attorneys and firms should conduct their own due diligence when selecting litigation support providers and reviewing service agreements.

You must be logged in to post a comment.