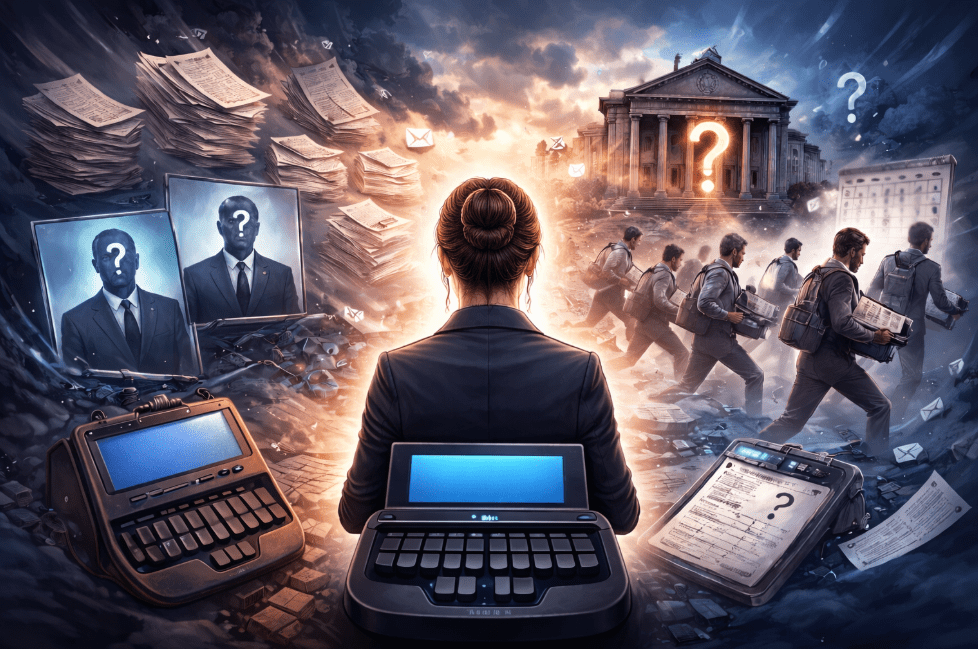

There is a quiet frustration spreading through the court reporting profession. It is not the familiar frustration of long calendars, late nights, or difficult testimony. It is something more structural, more corrosive. It is the feeling that the profession is increasingly being reduced to a logistical checkbox, rather than treated as the professional safeguard of the legal record.

Many reporters describe it the same way: the system no longer seems designed to support accuracy, transparency, or lawful process. It is designed to fill a slot.

Get a body. Any body. Move on.

In the past, assignments carried context. Reporters were told who the parties were, which firm was appearing, who had ordered the record, and what kind of proceeding it was. There were business cards passed across conference tables. There were whispered clarifications before the record went on. There was a shared understanding that a legal proceeding was not simply an event to be covered, but a formal process that required documentation, authority, and traceability.

Today, many reporters log onto remote platforms where names appear as floating rectangles, often without firm affiliations, sometimes without full surnames, occasionally without even real identifiers. Attorneys appear from bedrooms, cars, or offices. Some never announce who they represent. Some never formally identify themselves at all. And yet, at the same time, reporters are increasingly required to place their own full names and license numbers on the record, as if the only identity that truly matters is the one that carries liability.

The imbalance is not subtle.

Court reporters are trained to authenticate proceedings. The transcript is not merely a record of words. It is an evidentiary document. It must reflect who appeared, in what capacity, on whose behalf, and under what authority. These details are not optional formalities. They are part of what gives the transcript legal meaning. Without them, a record becomes harder to use, harder to challenge, harder to trust.

Yet in the modern assignment pipeline, those details are often missing before the reporter ever signs on.

Reporters routinely receive assignment sheets that provide little more than a time, a platform, and a case name. Party information is absent. Ordering parties are unclear. There is no confirmation of representation. There is no verification of whether a court already has a staff reporter assigned. There is often no meaningful research at all. The assignment exists not because the proceeding has been vetted, but because a client requested “a reporter” and the agency must deliver one to justify billing.

The result is a phenomenon many reporters quietly call the “warm body” problem.

The system does not prioritize whether the reporter is needed. It does not prioritize whether the appearance is authorized. It does not prioritize whether a staff reporter is already assigned. It prioritizes only whether someone can be placed into the slot so the transaction can proceed.

This has real consequences.

Reporters are increasingly sent into courtrooms that already have official reporters. They are booked on matters where multiple reporters unknowingly appear for the same proceeding. They are placed into remote sessions where no one can clearly state who the parties are or who ordered the record. They are expected to build a legally valid record in an informational vacuum.

When they raise concerns, they are often told it is not their problem.

If a court already has a reporter, that is the court’s issue.

If party information is missing, that is the client’s issue.

If attorneys fail to identify themselves, that is beyond the agency’s scope.

The reporter’s role, they are told, is simply to show up.

But this redefinition of the role is deeply at odds with the reality of what reporters are asked to certify.

A court reporter’s certificate does not say, “I was present.” It says, in substance, that the transcript is a true and correct record of the proceeding and that the reporter was authorized to report it. Authorization is not a metaphysical concept. It flows from jurisdiction, assignment, and the legal context of the proceeding. When that context is stripped away upstream, the reporter becomes the only remaining point where legality and process can still surface.

And that is precisely where the tension now lives.

Reporters are expected to place their credentials on records that agencies have not meaningfully vetted. They are asked to assume professional responsibility for proceedings whose structural details were never confirmed. They are placed into situations where they must extract basic identifying information on the fly, on the record, in front of judges and attorneys, while simultaneously being told they are “just there to take down what is said.”

The profession is being asked to function as a legal instrument without being given legal infrastructure.

Remote practice has intensified this problem. In physical courtrooms, many of these details were ambient. You could see who was present. You could read the room. You could identify counsel tables and hear formal appearances. Remote platforms flatten all of that. They turn legal proceedings into grids of audio feeds and usernames. Without deliberate procedural discipline, essential information simply disappears.

And increasingly, no one upstream is tasked with preserving it.

Agencies often do not collect party designations even when their own forms request them. They do not confirm representation. They do not verify whether courts have in-house reporters. They do not research whether an appearance is authorized or duplicative. The financial model rewards coverage, not compliance. It rewards volume, not verification.

So the burden slides downward.

It lands on the reporter who is now expected to reconstruct, in real time, the procedural scaffolding that should have existed before the assignment was ever dispatched.

This creates a daily low-grade moral injury within the profession. Reporters know what a proper record requires. They know what information is supposed to be established. They know what they are certifying. And they know how often they are being set up to do it without support.

Over time, that gap erodes professional identity.

When a reporter is treated as interchangeable labor rather than as an officer of the record, the message is clear: precision is optional, context is expendable, and the transcript is just another deliverable. But the law does not treat transcripts that way. Judges do not treat transcripts that way. Appellate courts certainly do not treat transcripts that way.

Only the assignment pipeline does.

The “warm body” problem is not about individual agencies or individual mistakes. It is about a system that has quietly inverted its priorities. The profession exists to preserve the integrity of legal proceedings. The modern logistics framework exists to process requests. When those two purposes conflict, logistics is currently winning.

And court reporters are the ones absorbing the friction.

They are the ones asking unanswered questions.

They are the ones navigating duplicative assignments.

They are the ones being placed on records that arrive stripped of identity and structure.

They are the ones whose names and license numbers remain permanently attached to the final product.

The frustration reporters feel is not resistance to change. It is resistance to erasure. It is the instinctive understanding that when a profession built on precision is treated as a commodity, the first casualty is not comfort. It is credibility.

The solution is not nostalgia. It is accountability.

Assignments must carry verified information. Agencies must treat party identification as essential, not optional. Courts with staff reporters must be respected as such. Remote appearances must require formal on-the-record identifications. And reporters must be recognized not as warm bodies, but as the final custodians of legal reality.

Because a transcript is not created by presence alone.

It is created by authority, context, and professional judgment.

And those cannot be automated, outsourced, or skipped without cost.

🔹 Disclaimer

This article reflects commentary and professional opinion based on industry experience and observed trends within the court reporting field. It is not intended as legal advice, nor does it allege misconduct by any specific company, court, or individual. The purpose of this piece is to encourage discussion, reflection, and higher professional standards surrounding the creation and preservation of the legal record.