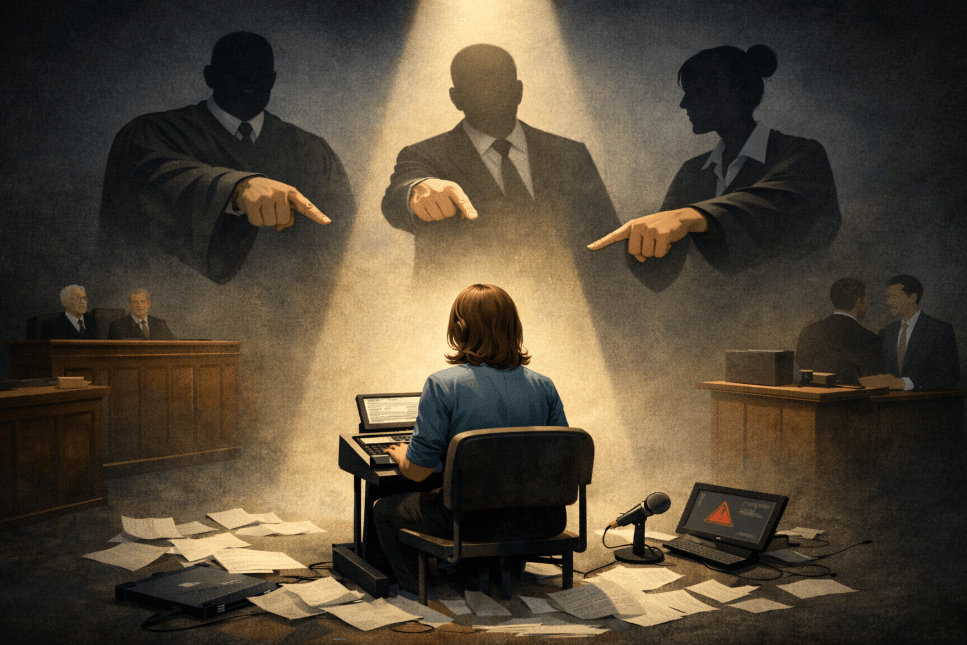

Court reporting is often described as a neutral profession. The reporter sits quietly. The machine runs. The words flow. The record appears, clean and objective, as if it simply exists. But anyone who has worked inside a courtroom or deposition room knows that the legal record does not emerge from neutrality. It emerges from pressure. And in systems under pressure, responsibility does not fall where it is most deserved. It falls where it is most survivable.

In many modern courtrooms, the stenographic reporter has become the system’s shock absorber.

When calendars overflow, when budgets tighten, when technology is rushed in before it is ready, when attorneys are unprepared, when judges are understaffed, when agencies overpromise, when courts are measured by throughput rather than integrity, the system quietly sorts its risk. Not in meetings. Not in memos. But in outcomes. Delays are smoothed over. Standards are relaxed. Authority is blurred. And when something finally fractures, the question is rarely “What failed?” It is “Who can carry this?”

Court reporters are uniquely positioned to carry it.

They are visible but rarely protected. Central to the process but structurally isolated. Essential to the product, yet peripheral to decision-making. They touch every part of the legal system, but belong fully to none of them. They are officers of the court without institutional power. Independent professionals operating inside hierarchies they do not control.

That makes them ideal containers.

When audio fails, when transcripts are delayed, when hearings go off the rails, when remote platforms glitch, when attorneys talk over one another, when records become unusable, the narrative almost always drifts toward the same conclusion: the reporter.

Not because the reporter caused the failure, but because the reporter is where accountability is easiest to place.

This is how scapegoating actually works in professional systems. It is not driven by cruelty. It is driven by triage.

Courts are under extraordinary pressure. Administrators are tasked with impossible ratios. Judges are expected to move calendars that would have broken courts twenty years ago. Agencies are squeezed by private equity models that reward scale, not sustainability. Attorneys are managing crushing caseloads inside adversarial structures that leave little room for reflection. Everyone is managing risk, reputation, and continuity at once.

So when something goes wrong, the system does not ask who is most responsible. It asks who is most absorbent.

Who is least likely to escalate.

Who is least shielded.

Who is most accustomed to adapting.

Who can carry the discomfort without destabilizing the machine.

Court reporters, by training and temperament, are problem solvers. They are conditioned to hold chaos and produce coherence. They correct speakers, repair records, manage equipment, smooth exchanges, protect accuracy, and recover proceedings in real time. They are relied upon precisely because they do not collapse when conditions are poor.

That competence is often misread as capacity.

And capacity, over time, becomes an invitation to carry what others cannot.

In pressured environments, the scapegoat is rarely the weakest person. More often, it is the person who sees the system clearly enough to register its failures and steady enough to survive being associated with them. The one who names problems. The one whose work reflects breakdowns. The one whose role makes structural issues visible.

The record is where everything converges.

If attorneys speak too fast, it shows up in the transcript.

If proceedings are disorderly, it shows up in the transcript.

If technology is unstable, it shows up in the transcript.

If access is cut, if accommodations fail, if audio is distorted, if instructions are unclear, if exhibits are mishandled, if witnesses are remote, if platforms glitch, it all lands in one place.

The record.

And by extension, the reporter.

From the system’s point of view, this rarely feels malicious. It feels managerial. A way to contain disruption. A way to restore confidence without confronting the architecture that produced the failure. It feels easier to question a transcript than a procurement decision. Easier to blame a reporter than to challenge a scheduling model. Easier to critique performance than to examine design.

From the reporter’s side, it feels deeply personal.

It feels like professional erosion. Like being trusted with everything and defended in nothing. Like being essential until the moment something goes wrong, and invisible the moment support is needed. It feels like competence becoming a liability. Like integrity becoming friction.

Many reporters internalize this. They work harder. Buy more equipment. Take fewer breaks. Apologize for conditions they do not control. Accept blame for outcomes they did not design. They try to out-perform structural problems.

But scapegoating does not resolve pressure. It redistributes it.

Every time accountability is passed downward instead of addressed upward or outward, the system trains itself to continue. Every time the reporter absorbs the failure, the environment is relieved of the obligation to change.

And over time, this has consequences.

Burnout rises. Attrition accelerates. Institutional knowledge disappears. Training pipelines weaken. The profession becomes quieter, more compliant, more brittle. The very people most capable of safeguarding the record are slowly pushed out of the structures that need them most.

Scapegoating ends only when protection is no longer concentrated at the top, when consequences do not default to those with the least leverage, and when leaders are supported to hold problems instead of transferring them.

For court reporting, that means something fundamental has to shift.

It means courts examining workflow before questioning transcripts.

It means agencies being held accountable for the systems they deploy.

It means judges being supported in enforcing procedural order.

It means attorneys recognizing their role in record integrity.

It means institutions treating reporters not as service providers, but as infrastructure.

And for reporters themselves, it means learning to see the pattern clearly.

Not to become cynical.

Not to become adversarial.

But to stop confusing structural behavior with personal failure.

When the environment repeatedly places responsibility where protection is thinnest, that is not a reflection of worth. It is a reflection of design.

Understanding that difference does not solve the problem. But it changes where you locate it.

And that is where real leverage begins.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and are offered for educational and commentary purposes only. They do not constitute legal advice, professional counseling, or psychological diagnosis. This article is intended to encourage discussion about systemic workplace dynamics and the role of certified court reporters in safeguarding the legal record.