Every February, during Court Reporting & Captioning Week, the legal services industry fills social media feeds and inboxes with appreciation campaigns. Vendors thank reporters, agencies praise the profession, and companies attempt to recruit talent in a shrinking labor market. The messaging is upbeat and communal: a celebration of the people who preserve the spoken word inside courtrooms and depositions.

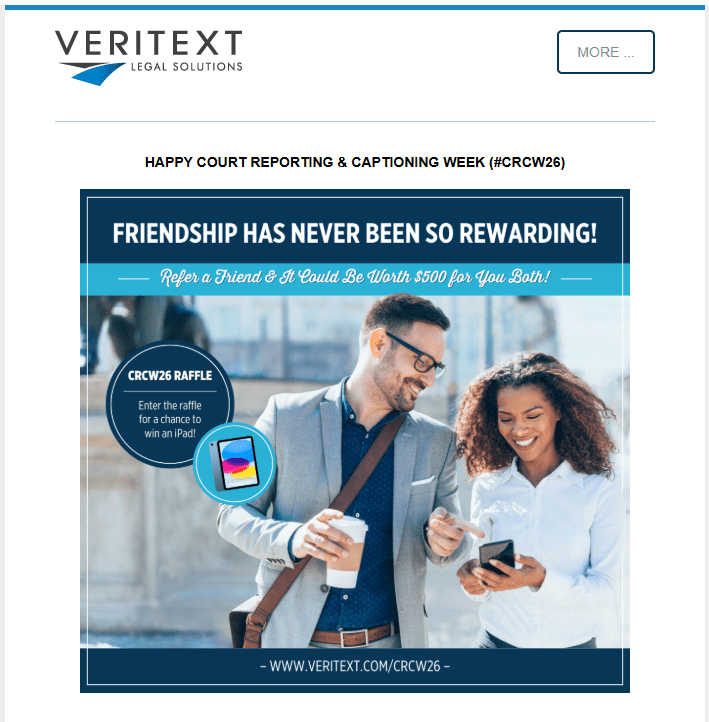

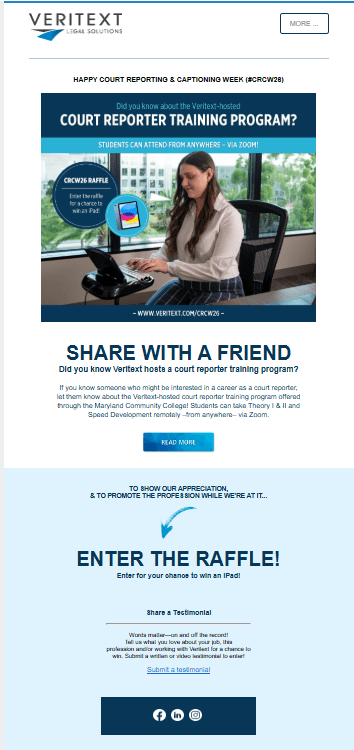

This year, one promotional campaign circulated widely among reporters. It invited recipients to refer colleagues, submit testimonials, and participate in a drawing for a prize — an iPad. The tone was celebratory. The intention appeared benign. The structure, however, raised a far less festive question.

Under California law, was it actually a raffle?

The distinction matters because raffles are not merely marketing devices. They are a regulated form of gambling. And outside of narrow charitable exceptions, they are illegal for commercial entities to operate.

Many industries casually use the language of “raffles,” “giveaways,” and “drawings” interchangeably. In retail or entertainment, such promotions often pass without scrutiny. But the legal services industry operates in a uniquely regulated environment. Court reporters are not ordinary marketplace participants; they are custodians of the evidentiary record. The companies that engage them function within a judicial ecosystem where compliance rules extend beyond consumer advertising norms.

California Penal Code sections governing lotteries define them broadly. A lottery exists when three elements are present: a prize, chance, and consideration. The prize in this case is obvious — a consumer electronic device offered as a reward. Chance exists because the winner is selected randomly. The remaining element, consideration, is the one most frequently misunderstood.

Consideration does not require payment.

Courts and regulators have long recognized that something of value may include labor, promotion, endorsement, referrals, or other acts benefiting the organizer. When participants must submit a testimonial, recruit another worker, or otherwise provide marketing value in order to enter, they are not merely receiving a gift opportunity. They are exchanging effort for a chance at a prize.

That exchange transforms a sweepstakes into a raffle.

In California, raffles are only lawful under the Charitable Raffle Program administered by the Department of Justice. The program permits qualified nonprofit organizations — and only those organizations — to conduct raffles after registration and annual reporting. Even then, the majority of proceeds must benefit charitable purposes. For-profit businesses are not permitted to operate raffles for commercial recruitment or advertising.

The practical implication is striking: a promotion designed to attract freelance professionals may inadvertently cross into prohibited territory if participation requires work or endorsement.

Marketing departments frequently attempt to avoid this problem by labeling promotions as sweepstakes. A legitimate sweepstakes, however, must provide a free and equal alternative method of entry requiring no effort beyond basic submission. Participants cannot be compelled to recruit, promote, endorse, or perform labor to qualify. If they must, the element of consideration exists regardless of whether money changes hands.

This distinction has become increasingly important in the court reporting field because the profession itself occupies an unusual position. Reporters operate as independent contractors but simultaneously serve a quasi-official role in litigation. Their neutrality and independence underpin the reliability of testimony. Incentive structures that resemble promotional campaigns blur that line, shifting the relationship from professional engagement to brand participation.

Legal scholars often describe evidentiary professions as trust-dependent occupations. Unlike typical service providers, their value is inseparable from perceived impartiality. When companies encourage participation through chance-based rewards, it risks altering how the profession is perceived by courts, attorneys, and the public. The issue is not simply compliance with advertising law; it touches on the integrity of the record itself.

The situation has precedent. In recent years, disputes have surfaced within the reporting community concerning promotional contests and recruitment incentives. Each time, the central misunderstanding remained the same: participants assumed that because no money was required, the promotion could not be gambling. The law does not agree. Consideration has never been limited to currency. Time, labor, and endorsement can hold equal or greater value.

The growing competition for skilled reporters has intensified the use of creative recruitment strategies. Companies now operate in a hybrid labor environment shaped by technological change, remote proceedings, and consolidation in litigation services. The temptation to borrow marketing techniques from gig-economy platforms is understandable. Yet those platforms do not operate inside a judicial framework. Legal proceedings impose higher standards precisely because the consequences of compromised trust extend beyond commerce into due process.

None of this suggests malicious intent. Most promotional campaigns arise from marketing enthusiasm rather than deliberate noncompliance. But legality does not depend on intent. Regulatory violations often emerge from borrowed practices that function harmlessly in other industries but conflict with statutes governing legal work.

There is also a practical risk to the workers themselves. When participation in recruitment is incentivized through chance-based rewards, it may alter how regulators view the relationship between company and contractor. Activities resembling lead generation or promotional labor can complicate classification analyses already under scrutiny in multiple jurisdictions. What begins as a celebratory campaign can unexpectedly intersect with labor and advertising law at once.

The solution is neither complicated nor burdensome. Companies wishing to run promotional events may structure them as true sweepstakes by removing required effort. Alternatively, they may compensate participants directly for testimonials or referrals, treating the exchange as paid work rather than chance. Direct payment is lawful; gambling promotion is not.

For a profession dedicated to verbatim accuracy, clarity in this area would serve everyone. Agencies avoid regulatory exposure. Reporters avoid participating in questionable promotions. Courts preserve confidence in the independence of the record.

Court Reporting & Captioning Week exists to honor a profession built on precision. Ironically, the difference between lawful recognition and unlawful lottery rests on precision of language and structure. A single requirement — refer a colleague, submit praise, promote participation — can change the legal character of an entire campaign.

In an industry whose purpose is to capture words exactly as spoken, the details matter.

Sometimes, they matter enough to determine whether a celebration is simply appreciation — or legally defined gambling.

Disclaimer

This article provides general informational analysis regarding promotional compliance issues and does not assert unlawful conduct by any specific organization. It is not legal advice. Entities should consult qualified legal counsel regarding sweepstakes, raffles, and advertising regulations in their jurisdiction.

Not sure who writes these blogs but this is good and clearly directed at Veritext. I saw the FT promotion referenced.

Debra A. Levinson

DALCO Reporting, Inc.

Sent from my iPhone

LikeLike