In courtrooms and conference rooms across the country, a quiet transformation is taking place in the handling of sworn testimony. For generations, the deposition transcript stood alone: a verbatim record created by a neutral officer whose duty was limited to capturing words exactly as they were spoken. The record contained no interpretation, no commentary, and no conclusion. Its authority rested on that restraint.

Today, the transcript is no longer the final product. Increasingly, court reporting agencies now offer an additional service: automated summaries generated by artificial intelligence and sold alongside the official record. Attorneys may purchase condensed narratives explaining what witnesses said, often within minutes of receiving the transcript. The summaries promise efficiency and convenience, and in a profession shaped by deadlines, both are welcomed.

But the practice has introduced a new and unsettled question into the legal system. When a sworn record becomes the source of a commercial interpretation, does the neutrality of the reporter who created it remain intact?

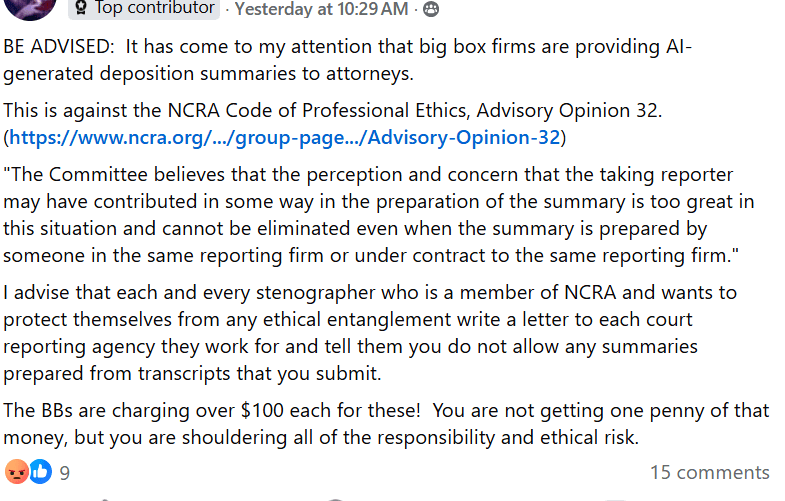

The debate has centered on a decades-old ethics guidance, Advisory Opinion 32 of the National Court Reporters Association. The opinion predates machine learning and litigation platforms by decades, yet it has become the focal point of an argument about whether technology has altered the boundaries of the reporter’s role or merely obscured them.

The answer depends less on what software does than on what the legal system believes the reporter has done.

The Record, the Algorithm, and the Appearance of Neutrality

Advisory Opinion 32 was written to address a simple situation. The ethics committee considered whether a court reporter could prepare a summary of testimony taken in a deposition. The committee concluded the reporter should not. The reason was not accuracy, competence, or even bias. It was perception. If the same neutral officer responsible for preserving testimony also produced an explanation of it, a litigant could reasonably believe the reporter exercised judgment about the meaning of the evidence. Even if the summary were written by another employee of the same reporting firm, the association could not be eliminated. The public might still assume the reporter contributed to the interpretation.

The opinion therefore protected not only neutrality but the appearance of neutrality. The reporter’s function was to capture words, not to explain them.

Artificial intelligence has complicated that principle by inserting a new actor between record and reader. The modern workflow often proceeds as follows: the reporter captures testimony, the agency distributes the transcript, software analyzes the text, and the agency sells the resulting summary. The reporter neither requests nor reviews the analysis. In many cases the reporter does not know it exists. Because no human connected to the reporter wrote the summary, some have concluded the ethical concern disappears.

Neutrality for Sale – When Platform Logic Rewrites Court Reporter Ethics

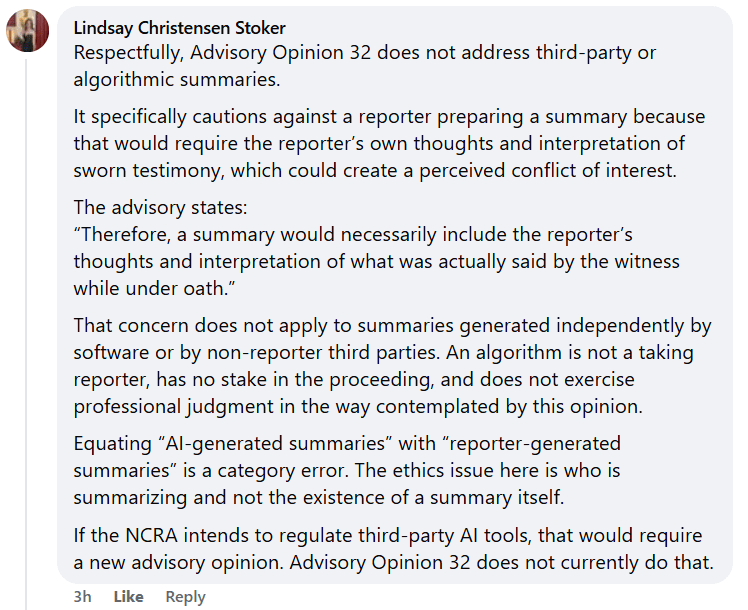

Among those presenting that conclusion publicly is industry commentator Lindsey Stoker, who has argued that automated summaries fall outside the scope of the ethics opinion because software is not a certified reporter and therefore cannot implicate the reporter’s professional duties. The assertion has been framed as settled interpretation, offered without judicial ruling, disciplinary precedent, or regulatory guidance confirming it.

The confidence of the conclusion exceeds its legal foundation.

Stoker is also affiliated with Filevine, a litigation technology platform whose ecosystem benefits from the continued availability of automated transcript-analysis tools. That relationship does not invalidate her reasoning, but it provides context: the interpretation she advances aligns with a commercial model that depends on third-party software vendors generating analytic products from deposition testimony. In professional ethics debates, positions that intersect with active business interests typically warrant heightened scrutiny, particularly where the conclusion would normalize a revenue-producing service whose regulatory status remains unresolved.

Ethics rules governing neutral officers have rarely depended on authorship alone. Courts regularly examine whether conduct creates the appearance of influence, not merely whether influence occurred. Judges recuse themselves for potential bias, not proven bias. Attorneys disclose conflicts that may never materialize. The law recognizes that trust in process is as important as the process itself.

Advisory Opinion 32 follows that tradition. The committee did not ask who physically wrote the summary. It asked whether an observer could reasonably believe the reporter was connected to an interpretation of testimony. Artificial intelligence does not eliminate that perception. In certain business models, it may reinforce it.

When summaries are marketed through the same portal that delivers the transcript, when they derive exclusively from the official record, and when they are sold by the same provider that arranged the reporting services, the distinction between record and explanation becomes invisible to the user. From the attorney’s perspective, the summary appears to carry the authority of the record itself. The consumer of the service is not expected to parse corporate structures separating reporter, agency, platform, and vendor. Ethics rules exist precisely because participants in litigation cannot investigate those relationships before relying on the record.

The claim that the ethics concern disappears because software authored the summary treats the rule as if it regulated typing rather than trust. It converts a principle designed to protect confidence in neutrality into a technical question about who pressed the keys.

The practical consequences extend beyond theory. If an automated summary mischaracterizes testimony and influences litigation strategy, the dispute ultimately returns to the transcript. Attached to that transcript is the sworn officer who created it. The software company is not called to authenticate testimony. The reporter may be asked to clarify what the witness actually said, provide declarations, or respond to challenges arising from the interpretation. Even if the reporter bears no fault, the reporter becomes entangled in a disagreement over meaning, precisely the circumstance the ethics opinion sought to prevent.

This exposure has prompted some reporters to notify agencies they do not authorize derivative interpretive products generated from their transcripts. The notices do not attempt to stop the summaries. They serve to document separation, establishing that the reporter neither prepared nor endorsed any explanation of testimony. The need for such disclaimers illustrates that the boundary between record and interpretation is no longer obvious.

Economic incentives further complicate the matter. Deposition summaries were historically attorney work product prepared by lawyers and billed hourly. Automation has converted interpretation into a purchasable commodity. Reporting agencies now monetize not only the capture of testimony, but its analysis. The reporter’s transcript provides the foundation for the product, yet the reporter exercises no control over how testimony is characterized while remaining attached to the authority that gives the characterization value.

This shift has produced a structural gap between professional duty and commercial practice. The reporter remains the neutral officer responsible for the record’s credibility, while the meaning of that record becomes a marketable add-on.

Stoker’s position, that automated summaries categorically fall outside the ethics rule, attempts to resolve the gap by redefining the rule’s reach rather than examining its purpose. The reasoning depends on the absence of precedent as proof of safety. Yet the absence of precedent in emerging technology rarely establishes certainty. It usually marks the point before adjudication occurs.

To present a contested interpretation as authoritative risks more than disagreement. It risks reshaping professional expectations before courts or regulators have addressed whether attribution, not authorship, governs the reporter’s neutrality in the era of automated analysis.

The issue ultimately turns on a broader question: whether testimony is treated as data or as sworn evidence requiring human stewardship. If testimony is merely information, automated interpretation presents little concern. If testimony carries the weight the legal system has historically assigned it, then any commercial explanation attached to the official record must be unmistakably separate from the authority of the officer who created it.

The legal system has long chosen the latter view. Evidence differs from information because it influences rights, obligations, and outcomes. The reporter’s oath exists to preserve confidence that what is recorded reflects only what was said. The more closely interpretation travels with the record, the more that confidence depends on the clarity of their separation.

Artificial intelligence has not changed the reporter’s duty. It has changed the environment surrounding it. Words once preserved and then interpreted by advocates can now be interpreted automatically and sold beside the record itself. The technology functions efficiently. The ethical boundary, however, remains unsettled.

Courts, bar associations, or regulatory bodies will eventually decide whether automated interpretive products attached to the official transcript alter the perception of neutrality. Until then, assertions of certainty are premature. The question has not been resolved; it has merely been postponed by convenience.

The reporter’s role has always rested on restraint. The authority of the transcript comes from the understanding that the record speaks for itself. As technology grows capable of explaining testimony instantly, the legal system must determine whether that explanation travels independently or under the shadow of the oath.

The distinction will decide whether the reporter remains the silent custodian of words or becomes, however unintentionally, connected to their interpretation.

Disclaimer

This article is commentary and analysis for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice or an ethics ruling. Readers should consult applicable statutes, court rules, and professional licensing authorities in their jurisdiction for guidance regarding specific practices.

Again, an outstanding dissection of a complicated topic. Thank you.

This begs the question: Can a reporter extricate themselves from a prohibited practice simply by sending a pithy letter to their firm, even though they have full knowledge that the prohibited practice will definitely occur?

On the business side, large national firms have the deep pockets to fight this, while the mid-size, boutique reporting firms, and independent freelance reporters do not. This creates unfair competition.

Sadly, here in Arizona there’s little or no enthusiasm by the Bar to address any of these issues, so the non-nationals will continue to be pummeled with outdated regulatory restraint that never was meant to address today’s technology.

Thanks again for all you do.

Marty Herder, CCR

Herder & Associates, Inc. Two N. Central Avenue, Suite 1800 Phoenix, AZ 85004

(480) 481-0649

[cid:8039f0ae-f110-4c66-9fd1-179522630e16]

Past President, Arizona Court Reporters Association

Past Arizona Delegate, National Court Reporters Association (3 terms)

LikeLike

Thank you, Marty — and you’re asking the right question.

A notice letter does not “legalize” or stop the practice, and it is not meant to. Its purpose is evidentiary separation. AO-32 is concerned with the appearance that the reporter participated in or is affiliated with an interpretation of testimony. When a reporter affirmatively documents that they neither authorize, review, nor endorse derivative summaries, they are establishing that they are not part of the interpretive function. In other words, the letter does not cure the underlying industry issue, but it helps prevent the reporter from being treated as the source of the interpretation if the summary later becomes disputed.

You are also correct about the competitive imbalance. Larger vendors can absorb uncertainty while smaller firms and independents carry disproportionate exposure, even though the ethical duties attach to the individual reporter, not the platform distributing the product. That tension is exactly why clearer guidance is needed. The goal should not be to freeze technology in place, but to ensure that modernization does not blur the line between the neutral record and interpretive services in a way that shifts risk onto the reporter.

Until regulators or bar associations address it directly, reporters are left managing risk individually, which is an imperfect substitute for uniform standards

LikeLike

So since we’ve been well conditioned to believe as CSRs we don’t “own” the record, but we carry the responsibility and oath to be its guardian and to speak as to its neutrality and represent its unadulterated existence, who’s having their cake and eating it too or it might be a fit to ask, has someone cut their nose off to spite their face?

It is definitely not a situation that can be silo’d or looked at in a vacuum.

You broached an interesting topic of derivatives and labor issues.

At what point are we as CSRs cut out of the remuneration loop, especially since we created the present existence of the record on our backs, on our skill, on the wings of an industry that is as old and established as time itself, with and by use of equipment and tools and the skill of the trade we purchased and invested in? As far as I am concerned, our work product fee structure is multi-tiered and not based on a flat-fee structure. When you needed to access that information, there was one transcript available per office under most circumstances. Now it’s a free-for-all.

I interviewed awhile back for a federal official ship. There was a gig going on there where a group of Scopist’s (3) prepare the daily and the reporter can just sit back and relax and “write” and not have to concern him/herself with the certifying process.

I said a hard “no” to that “opportunity.”

Here’s what we’re guarding and blocking:

Labor issues Neutrality and issues of bias Chain of custody Commercialism

Creating a hybrid model of this cornerstone is a whole other universe. But if it’s going to happen, bring the responsible party to the table. All of us. Not like when my federal superiors would call our program in to discuss “changes” but had already decided the outcome but wanted to give the appearance that our program was consulted and that we are onboard.

Since we all know it’s about the money, that’s the conversation. But from our point of view as the responsible party, if that is severed, how is the work kept whole, its structures and values intact and aligned, along with its incentive?

All these people with their hand in the cookie jar, wanting a piece of the court reporter remunerations and feel entitled to it because it on its face the record looks ripe for the taking. Far from it. It’s like the Arc of the Covenant.

LikeLike

You’re putting your finger on the tension that sits underneath all of this. The reporter has never “owned” the record in a property sense, but historically the reporter has been the responsible custodian of its integrity. What is changing now is that interpretation and commercialization of the record are being separated from the person who still carries the certification and neutrality obligation. That creates a structural mismatch: accountability remains with the reporter while control over derivative use does not.

The question is not simply compensation, although that is part of it. It is chain of custody of meaning. If the testimony can immediately be transformed into analytical or narrative products by parties outside the certification process, then the profession has to decide whether those products are independent litigation support or functionally extensions of the reporting service. The answer determines both ethical exposure and economic impact.

I agree this cannot be addressed in isolation or by individual reporters making private decisions. Without uniform guidance, smaller firms and independents bear disproportionate pressure because they operate under the same professional duties but without the scale to absorb uncertainty. That is less a technology problem than a standards problem.

Ultimately, modernization is inevitable, but the responsible party — the sworn officer whose name is attached to the record — cannot be treated as incidental to the downstream use of that record. If interpretation becomes detached from responsibility, then neutrality becomes theoretical rather than practical, and that is the line the profession has historically tried to avoid.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Here’s a way to gauge the temperature…

Since when did agencies become so bold as to tell a reporter when and how and under what circumstances they can contact others regarding the record, to whom the reporter can talk to, becoming the role of employer?

These are the type of things that give a hint to us about how others are posturing and for us not to be surprised or taken off guard.

LikeLike

That’s an important observation. The issue isn’t really about day-to-day communication preferences; it’s about who ultimately governs the record. A reporter is appointed or retained to create a neutral, certified record of proceedings, and that responsibility follows the reporter, not the intermediary arranging the job. When an agency begins dictating how and to whom a reporter may speak about the record, it starts to blur the distinction between coordinating logistics and controlling the officer of the record.

Most of these policies likely developed around workflow management and client relations, but they take on a different character when the record itself — and derivative uses of it — are involved. The more the record becomes a platform product rather than a professional act, the more pressure there is to treat the reporter as a component of a service rather than an independent officer with separate duties.

That tension is part of the broader question raised here: whether modernization is reorganizing the reporting process or redefining the reporter’s role within it

LikeLiked by 1 person

Two things can be true at the same time…

LikeLike