When a profession is under existential pressure, language matters. Comfort can be costly. Precision is survival.

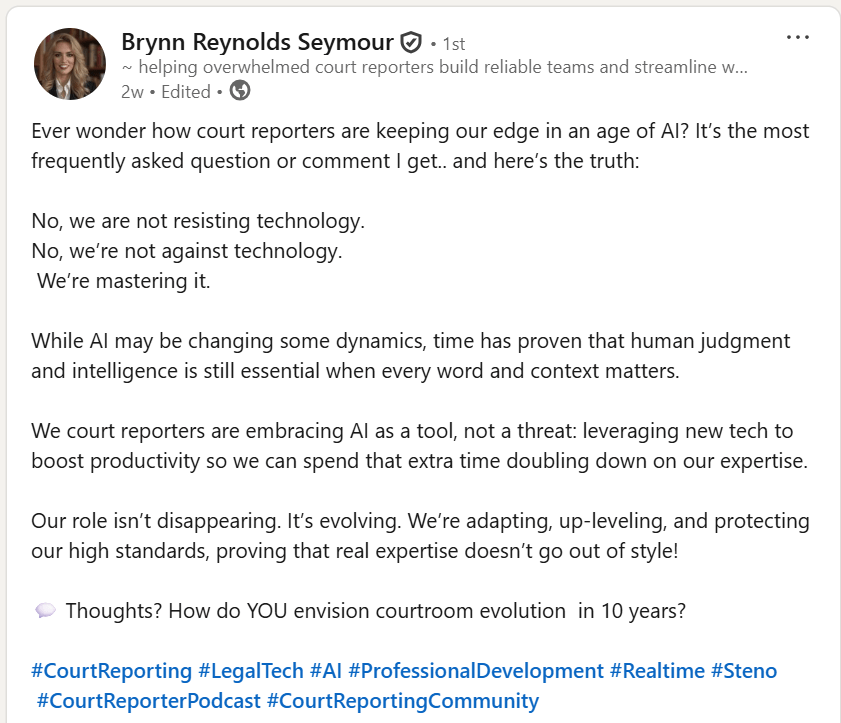

A recent LinkedIn post by a respected industry voice attempts to reassure court reporters—and the legal community—that stenography is thriving in the age of artificial intelligence. The tone is optimistic, collaborative, and future-oriented. Unfortunately, the substance blurs critical legal distinctions that attorneys, judges, and policymakers cannot afford to misunderstand.

Below is a line-by-line examination of that message, not to attack the author, but to correct the record.

“Ever wonder how court reporters are keeping our edge in an age of AI?”

Rebuttal:

This framing assumes that “AI” is simply another competitive pressure—like faster software or better microphones. It is not. Artificial intelligence is not merely changing how work is done; it is being deployed to change who creates the legal record. That distinction is foundational.

Court reporters are not competing with AI for efficiency. They are defending the legal integrity of the record itself.

“It’s the most frequently asked question or comment I get.”

Rebuttal:

That alone should signal urgency, not reassurance. When an entire profession is being asked whether it will survive a technology shift, the correct response is not branding language—it is legal clarity.

Attorneys are not asking this question out of curiosity. They are asking because vendors, courts, and agencies are actively pitching AI-generated transcripts as substitutes for certified human reporters.

“No, we are not resisting technology.”

Rebuttal:

This sentence implicitly accepts a false premise: that opposition to AI-only capture is “resistance to technology.”

Court reporters are not resisting technology. They are resisting the replacement of a legally recognized capture method with an unlicensed, non-certifiable process.

Realtime, CAT software, remote platforms, digital indexing, and secure transcript delivery are all advanced technologies. What reporters oppose is not innovation—but substitution.

“No, we’re not against technology.”

Rebuttal:

Repetition does not strengthen the argument; it dilutes it.

By over-correcting against the accusation of being “anti-tech,” the post avoids stating the truth plainly: some technologies are incompatible with due process. Not all tools belong in the creation of an official record.

The legal system has always limited technology when it threatens reliability, chain of custody, or admissibility. This is no different.

“We’re mastering it.”

Rebuttal:

Who is “we”?

Court reporters do not “master” ASR engines trained on opaque datasets, owned by third-party vendors, processed in the cloud, and governed by proprietary algorithms. Reporters neither control these systems nor certify their outputs.

Mastery requires authority. Authority requires licensure. AI transcription has neither.

“While AI may be changing some dynamics…”

Rebuttal:

This understates the reality. AI is not changing “some dynamics.” It is being marketed as a wholesale replacement for the human creation of the record—often without disclosure to parties, without informed consent, and without clear rules governing retention, access, or secondary use of the data.

That is not a “dynamic.” It is a structural shift with constitutional implications.

“…time has proven that human judgment and intelligence is still essential when every word and context matters.”

Rebuttal:

This statement unintentionally concedes too much.

ASR vendors already claim “human review.” They already claim “editor oversight.” They already claim “quality control.”

What they cannot provide—and what this sentence fails to defend—is contemporaneous human capture by a licensed officer of the record, with the authority to certify accuracy at the moment the words are spoken.

Judgment after the fact is not the same as responsibility at the moment of creation.

“We court reporters are embracing AI as a tool, not a threat…”

Rebuttal:

This is the most legally dangerous sentence in the post.

AI can be a tool when it assists a certified reporter.

AI is a threat when it replaces the reporter entirely.

Without explicitly stating that distinction, this line functions as an endorsement of AI-only capture systems—whether intended or not. Attorneys, judges, and legislators will read it exactly that way.

“…leveraging new tech to boost productivity so we can spend that extra time doubling down on our expertise.”

Rebuttal:

Productivity is irrelevant if the resulting record is inadmissible, challengeable, or ethically compromised.

Expertise in court reporting is not time management. It is accuracy under oath, neutrality under pressure, and legal accountability for the verbatim record. No amount of “extra time” compensates for the loss of those guarantees.

“Our role isn’t disappearing. It’s evolving.”

Rebuttal:

This is aspirational, not factual.

Roles are disappearing—in depositions, arbitrations, administrative hearings, and cost-constrained courts. They are not evolving into higher forms; they are being eliminated and replaced with vendor pipelines staffed by non-reporters.

Evolution implies continuity. What is happening instead is displacement.

“We’re adapting, up-leveling, and protecting our high standards…”

Rebuttal:

Standards are not protected by optimism. They are protected by enforcement.

High standards require:

- Licensed capture

- Clear statutory authority

- Defined chain of custody

- The ability to certify, correct, and authenticate the record

AI-only systems meet none of these criteria.

“…proving that real expertise doesn’t go out of style!”

Rebuttal:

Expertise does go out of use if it is not explicitly required.

The legal system does not preserve professions out of respect. It preserves them through rules, statutes, and enforceable standards. Without naming what makes court reporting legally distinct, this closing line reduces expertise to branding rather than authority.

Why This Messaging Matters

Comfortable language reassures insiders—but it educates outsiders incorrectly.

When attorneys hear that reporters are “embracing AI,” they assume substitution is acceptable. When judges hear there is no resistance, they see no procedural risk. When legislators hear optimism, they see no need for guardrails.

The profession does not need better vibes.

It needs clearer lines.

Technology is not the enemy.

But method matters.

And the failure to say that—clearly, publicly, and repeatedly—is how professions lose the record without ever losing the argument.

Disclaimer

This article reflects the author’s professional analysis and opinion based on experience in court reporting, legal procedure, and industry practices. It is not intended as legal advice, does not assert undisclosed facts about any individual, and does not allege misconduct. References to public statements are for commentary and critique in the public interest.

I love reading your emails. They are super informative. Would you mind putting one out that addresses digital reporters that oversee the transcript in realtime and make corrections on their keyboard as the testimony goes along in the realtime feed and what the dangers of that are?

Sincerely,

APEX COURT REPORTING

Cindy K. Pfingston, Registered Professional Reporter

Cindy@ApexCourtReporting.com Cindy@ApexCourtReporting.com

http://www.apexcourtreporting.com/ http://www.ApexCourtReporting.com

(605) 877-1806

LikeLike

I just wrote this article for you entitled: “When Software Tries to Stand In for a License – Why ASR “Cleanup” Is Not Court Reporting” – it will be published on January 5th.

LikeLike