Last week, a LinkedIn post quietly signaled a profound shift in how parts of the legal industry are beginning to think about the court record.

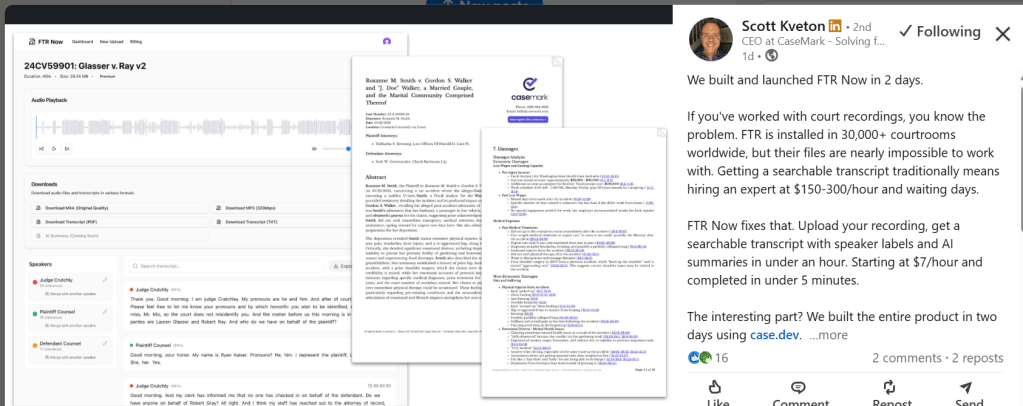

“We built and launched FTR Now in two days,” wrote Scott Kveton, CEO of CaseMark. The product, he explained, allows users to upload courtroom audio recorded on FTR systems and receive a “searchable transcript with speaker labels and AI summaries” for as little as seven dollars per hour of audio—delivered in minutes rather than days.

To many attorneys, particularly those under relentless pressure to reduce costs and accelerate litigation timelines, the pitch may sound like progress. Courtroom audio that has historically been cumbersome and opaque suddenly becomes searchable, summarized, and inexpensive. What’s not to like?

Quite a bit, as it turns out—particularly if one cares about the integrity of the record itself.

This article is not an argument against technology. Nor is it a nostalgic defense of tradition for tradition’s sake. It is an examination of what is gained, what is lost, and what is quietly assumed when automated transcription is positioned as a substitute—or even a proxy—for the official court record.

What FTR Now Actually Is

Stripped of marketing language, FTR Now is a post-processing tool layered on top of existing courtroom audio. It does not create the record. It does not monitor proceedings in real time. It does not intervene when speakers overlap, whisper, move away from microphones, or speak through emotion, accent, or obstruction.

Instead, it takes what already exists—audio captured by digital recording systems—and runs it through automated speech recognition (ASR), speaker diarization, and summarization models. The result is text. Quickly produced, inexpensive, and searchable.

That distinction matters.

Court reporters create records contemporaneously. They interrupt when a witness is inaudible, request clarification when speech is unclear, and mark the record when something cannot be accurately captured. Their role is not merely mechanical; it is judgment-based. ASR systems, no matter how advanced, do not exercise judgment. They calculate probabilities.

The “Two-Day Build” Should Raise Questions, Not Applause

Perhaps the most revealing claim in the post is not the price point or the turnaround time, but the speed of development.

“We built the entire product in two days,” Kveton wrote.

In software circles, this is framed as a triumph of modular infrastructure. CaseMark reused existing APIs—storage, transcription, format conversion, summarization—to spin up a new product almost instantly.

But in the legal context, this speed should prompt a different reaction. If a tool that purports to generate something called a “transcript” can be deployed in 48 hours, what vetting occurred? What legal standards were consulted? What court rules were examined? What ethics opinions were considered?

The answer appears to be: none that are mentioned, and none that are central to the pitch.

The Word Doing the Most Work: “Transcript”

Language matters in law, and the term “transcript” is not neutral.

A transcript is not simply text derived from speech. It is a formal representation of the official record, governed by statutes, court rules, and long-standing evidentiary principles. Certified transcripts carry legal weight precisely because they are created by authorized officers of the court who are accountable for their accuracy.

An ASR-generated text file—even a highly accurate one—is not the same thing.

Yet products like FTR Now blur that distinction intentionally or otherwise. To an untrained eye, a “searchable transcript” looks like a transcript. Attorneys may quote from it. Clients may rely on it. Judges may be presented with excerpts. Appeals may be influenced by it.

The legal system has seen this movie before: informal tools gradually assume formal authority without a corresponding change in rules or safeguards.

What Is Missing from the Pitch

The LinkedIn post highlights speed, cost, and convenience. It omits discussion of:

- Accuracy benchmarks under courtroom conditions

- Error correction workflows

- Human review thresholds

- Redaction and sealing protocols

- Privilege handling

- Chain of custody

- Certification

- Audit trails for edits

- Speaker misattribution risks

- Compliance with jurisdiction-specific rules

These are not minor details. They are the very features that distinguish an official record from a convenience product.

At seven dollars per hour of audio, there is no plausible economic model for meaningful human oversight. That is not a criticism; it is a mathematical reality.

The Real Problem Isn’t FTR Audio—It’s the Assumption That Audio Is Enough

The post correctly identifies a frustration shared by many attorneys: FTR audio files are difficult to work with. They are proprietary, often unwieldy, and poorly suited for fast review.

But that frustration should not be confused with proof that audio is an adequate substitute for a stenographic record.

Courtroom audio is subject to innumerable variables: microphone placement, room acoustics, sidebars, bench conferences, overlapping speech, and human behavior that does not conform to clean input-output models. Court reporters manage these variables in real time. Digital recording systems do not.

ASR systems inherit every flaw in the underlying audio—and add their own.

Cost Savings vs. Legal Risk

The promise of $7-per-hour transcription will inevitably attract attention from budget-conscious firms, particularly in discovery-heavy litigation. But cost savings achieved at the expense of reliability can become extraordinarily expensive downstream.

Misattributed testimony, missed objections, inaccurate quotations, or misunderstood rulings do not merely inconvenience attorneys; they can alter case outcomes. Unlike a certified reporter, an ASR system does not raise its hand to say, “That cannot be accurately captured.”

It simply outputs text.

A Familiar Pattern

Legal professionals have watched this progression before. Emergency measures become normalized. Convenience tools become default practices. “Temporary” solutions quietly replace established safeguards.

The pandemic accelerated many changes that were necessary and beneficial. It also lowered the industry’s resistance to unvetted technological shortcuts.

FTR Now fits neatly into that pattern. Its rapid development and deployment are not signs of inevitability; they are signs of how quickly standards can erode if speed is mistaken for progress.

Why Court Reporters Are Sounding the Alarm

Court reporters are often framed as stakeholders with something to lose. That framing is incomplete. They are also stakeholders with something to protect: the integrity of the judicial record.

Reporters understand, often better than anyone else in the room, how fragile that record can be—and how easily errors propagate once they enter the system.

When reporters raise concerns about ASR-based “transcripts,” they are not resisting innovation. They are pointing out that not all text is created equal, and not all records are interchangeable.

The Question Attorneys Should Be Asking

The relevant question is not whether products like FTR Now will exist. They will. The question is how they will be used, and whether attorneys understand the difference between a convenience tool and a record that can withstand scrutiny.

Searchable text is useful. AI summaries can be helpful. But neither replaces a certified transcript created by a human officer of the court with a legal duty to accuracy.

Speed is valuable. So is cost efficiency. But neither is a substitute for due process.

Progress Without Guardrails Isn’t Progress

FTR Now is not a scandal. It is not a villain. It is a case study.

It shows how easily automated transcription can be layered onto existing courtroom infrastructure, how quickly such tools can be deployed, and how tempting it is to conflate usability with reliability.

For attorneys, the takeaway should not be fear—but discernment.

The court record is not just data. It is the foundation upon which motions, appeals, and judgments rest. Treating it as a commodity rather than a legal instrument carries consequences that rarely appear in marketing copy.

Court reporters, uniquely positioned at the intersection of technology and the law, are raising these issues not to protect a profession, but to protect a system.

Attorneys would be wise to listen—before speed becomes the standard and accuracy becomes optional.

Disclaimer

This article is an editorial analysis intended for educational and professional discussion. It does not allege misconduct by any individual or company and does not constitute legal advice. References to products or technologies are based on publicly available statements and are discussed in the context of broader legal, ethical, and procedural considerations affecting the creation and use of court records.

Thank you for this thoughtful analysis. You raise important points that deserve a direct response from the team that built FTR Now.

First, I want to agree with your central premise: FTR Now does not produce official court records nor is it ever meant to replace human court reporters. We’re not claiming to, and we should probably be clearer about that distinction in how we describe the product. We’ve already updated the website.

Let me clarify what we actually built and why:

FTR Now is a case preparation tool for attorneys who already have FTR recordings sitting on their desks; recordings that are often effectively inaccessible because the proprietary format makes them difficult to work with. These attorneys need to review what happened in a proceeding, prepare for the next hearing, or search for specific testimony. They’re not looking to replace the official record; they’re trying to work with audio that already exists.

You’re absolutely right that court reporters do something fundamentally different: they create the record contemporaneously, exercise judgment, intervene when speech is unclear, and certify accuracy. That is irreplaceable. A stenographer in the room catches the whispered sidebar, requests clarification when a witness mumbles, and ensures the record is complete. ASR cannot do that.

What ASR can do is help attorneys navigate audio they already have access to; faster than listening in real-time, with timestamps to find specific moments, and searchable text to locate relevant testimony. That’s a different job than creating an official record.

On the “two-day build” concern: fair point. The speed reflects that we assembled existing, proven components (AssemblyAI’s transcription engine, which has been developed over years and the CaseMark AI-generated summaries we’ve been slaving over for 2+ years). We didn’t build speech recognition from scratch in 48 hours or whip up our AI summaries in a day. The point in delivering this in 48 hours was to prove that you can build competent solutions quickly if you leverage known, reliable components (in this case via case.dev). But you’re right that we should be more explicit about the appropriate use cases and limitations.

All that being said, I didn’t actually see anyone from StenoImperium actually utilize the service to give it a fair shake. If you had, you would have seen some of the features that make clear that we’re not trying to replace the court reporter but make it easier to work with what you have in the moment. BTW – if you’d like to try it for free, I’d be more than happy to set you up!

A few areas we’ve just tried to improve on with the site and the outputs we’re generating:

I appreciate this community raising these issues. The court record is foundational to due process, and the people who protect it should be part of conversations about how technology intersects with that work. We truly believe that and the 100+ court reporting firms that depend on our services know we feel that way.

— Scott Kveton, CaseMark

LikeLike