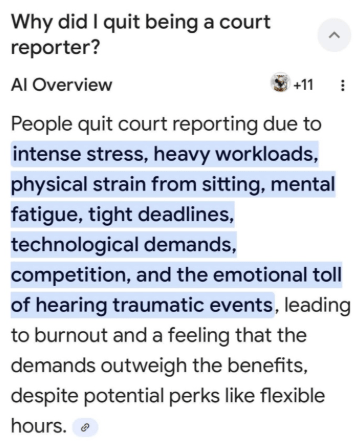

Every so often, an algorithm decides it understands a profession better than the people who have lived inside it for decades. The screenshot circulating online—an AI-generated explanation for why people “quit being court reporters”—is one of those moments. It reads confidently, ticks all the right modern boxes, and yet fundamentally misunderstands the profession it purports to summarize.

The premise itself is flawed. Court reporting is not a career people typically “try and abandon.” It is a profession people commit to for life. Three decades. Four decades. Often five. It is not uncommon to see multiple generations of court reporters in the same family, or to work alongside colleagues who began their careers before digital recording even existed. This is not the profile of a profession hemorrhaging workers due to unbearable conditions. It is the profile of a craft that rewards mastery, autonomy, and endurance.

That does not mean the job is easy. It never has been. Court reporting is demanding by design. It requires intense concentration, technical skill, emotional discipline, and an unusual tolerance for responsibility. The record must be accurate. The deadlines are real. The stakes are often high. But difficulty alone does not drive people away. In fact, for many reporters, it is precisely the rigor that keeps them engaged for decades.

The AI narrative leans heavily on “trauma” as a central reason reporters quit. That claim ignores a critical distinction within the profession. Many freelance reporters do not work criminal cases at all. They handle civil litigation, depositions, arbitrations, hearings, and proceedings where the emotional content, while sometimes stressful, is not inherently traumatic. For those reporters, the idea that emotional exposure is a defining occupational hazard simply does not apply.

More importantly, court reporting offers something many modern professions no longer do: control. Freelance reporters can turn down work. They can take time off when they need to stay sane. They can pace their careers in ways that protect both mental health and longevity. Burnout is far more likely in environments where workers are trapped, interchangeable, and powerless. Court reporters, by contrast, build careers around independence and choice.

Yes, some days are bad. Some days are truly awful. But that is not unique to court reporting—it is true of any profession that involves real responsibility. The difference is that reporters who stay learn how to manage time and stress as core professional skills, not afterthoughts. They learn quickly that physical activity is not optional. Movement keeps the body functioning and the brain sharp. This is not a lifestyle job for people who expect the work to accommodate them. It is a profession that demands adaptation—and rewards it.

The AI summary also treats “technological demands” as a reason people quit, as though learning and evolving were new burdens imposed on an otherwise static field. Court reporters have always adapted to technology. From manual machines to computerized steno, from paper notes to realtime feeds, from in-person proceedings to remote platforms, this profession has survived precisely because its practitioners are resilient, curious, and technically adept. Those who struggle with that reality self-select out early. Those who thrive stay for life.

And that is the point the algorithm misses entirely: not everyone is cut out to be a court reporter. That has always been true. It is a jealous mistress of a profession—demanding, exacting, and unforgiving of shortcuts. But for those who are wired for it, it becomes more than a job. It becomes an identity. A superpower. Something people proudly say they have loved for 40 or even 48 years, without irony or regret.

Finally, there is flexibility—real flexibility, not the buzzword version. Court reporters are not locked into one narrow path. They can change agencies. They can move geographically. They can pivot into captioning, CART, realtime, mentoring, or teaching. They can reinvent their careers without abandoning the profession itself. Very few careers offer that kind of lateral freedom without starting over.

So when an AI confidently declares why “people quit court reporting,” it is worth asking: which people? Because the overwhelming evidence, written in decades-long careers and generational legacies, tells a very different story.

Court reporting is not a profession people flee from. It is a profession people grow old in—by choice.

StenoImperium

Court Reporting. Unfiltered. Unafraid.

Disclaimer

“This article includes analysis and commentary based on observed events, public records, and legal statutes.”

The content of this post is intended for informational and discussion purposes only. All opinions expressed herein are those of the author and are based on publicly available information, industry standards, and good-faith concerns about nonprofit governance and professional ethics. No part of this article is intended to defame, accuse, or misrepresent any individual or organization. Readers are encouraged to verify facts independently and to engage constructively in dialogue about leadership, transparency, and accountability in the court reporting profession.

- The content on this blog represents the personal opinions, observations, and commentary of the author. It is intended for editorial and journalistic purposes and is protected under the First Amendment of the United States Constitution.

- Nothing here constitutes legal advice. Readers are encouraged to review the facts and form independent conclusions.

***To unsubscribe, just smash that UNSUBSCRIBE button below — yes, the one that’s universally glued to the bottom of every newsletter ever created. It’s basically the “Exit” sign of the email world. You can’t miss it. It looks like this (brace yourself for the excitement):