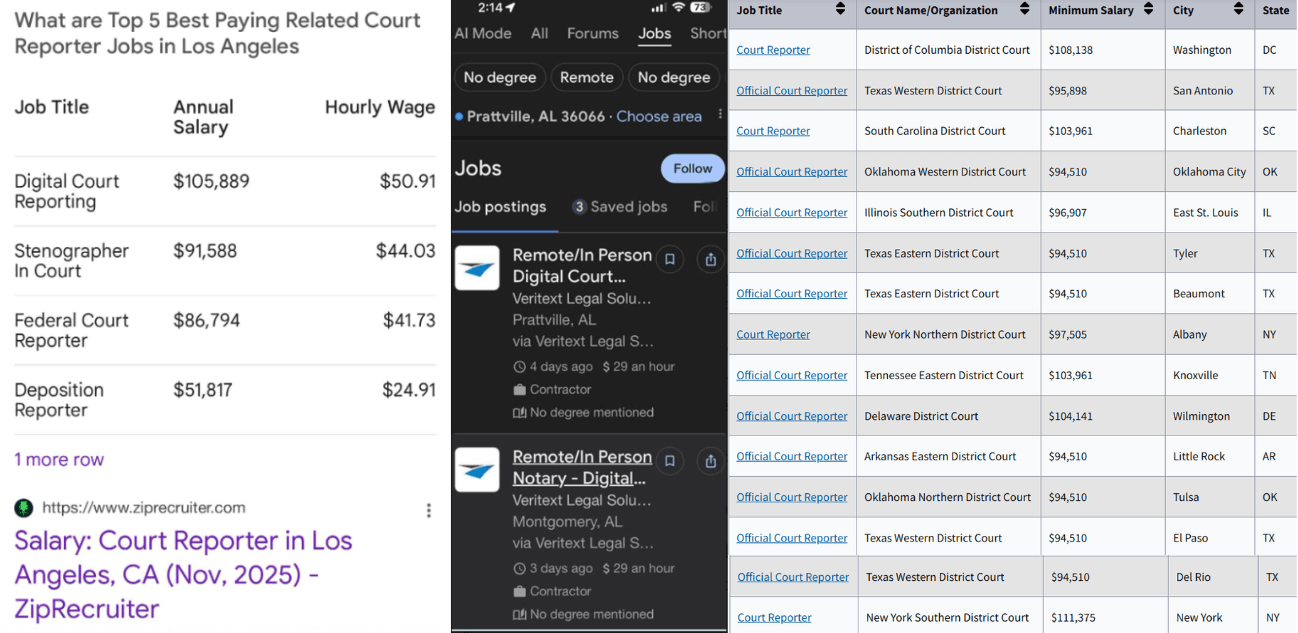

A recent viral post circulating on social media showcased a set of wage figures purporting to reveal the “Top 5 Best Paying Related Court Reporter Jobs in Los Angeles.” According to the graphic, “Digital Court Reporting” allegedly commands an annual salary exceeding $105,000 and an hourly rate north of $50, eclipsing traditional stenographic roles and even federal court reporting positions. For anyone who has spent time inside a courtroom, deposition suite, or the increasingly hybrid world of remote proceedings, the numbers are not merely surprising. They are deeply discordant with the lived economic reality of the profession.

This is not just a moment of sticker shock. It is a case study in how mischaracterized data, algorithmically generated content, and surface-level job aggregation distort an already fragile ecosystem. The court reporting profession, long grounded in skill, certification, and legal accountability, now finds itself competing with seductive but misleading narratives suggesting that minimally trained digital recorders are not only equivalent, but more financially rewarded.

At the heart of the issue is a fundamental misunderstanding of what constitutes a court reporter. A Certified Shorthand Reporter, or CSR, maintains rigorous licensing requirements, adheres to state and federal statutes, and produces an immediately usable, authenticated transcript of legal proceedings. By contrast, so-called “digital reporters” often perform a passive recording function. Their product is not a transcript but an audio file, which is then outsourced to an anonymous transcriber, frequently paid a fraction of the rate, sometimes overseas, and rarely subject to the same legal standards or accountability.

The claim that such a role commands a higher wage than the professional tasked with creating the certified record defies logic. It also underestimates the complex economics of stenographic work. Court reporters seldom earn a static hourly rate. Their income is derived from a combination of appearance fees, per-page transcript production, rush charges, real-time services, scopist and proofing coordination, and often extended hours that exceed the traditional 40-hour workweek. To view compensation through the simplified lens of hourly equivalence is to erase the multifaceted reality of the profession.

Consider the figure cited for deposition reporters, allegedly earning just over $51,000 per year. In high-volume jurisdictions like Los Angeles, experienced deposition reporters regularly exceed that amount in a fraction of the year. Many operate as independent professionals, not hourly employees, and shoulder the costs of equipment, software, continuing education, and insurance. Their compensation reflects both their technical expertise and their role as the guarantor of an accurate record in proceedings that can have far-reaching legal consequences.

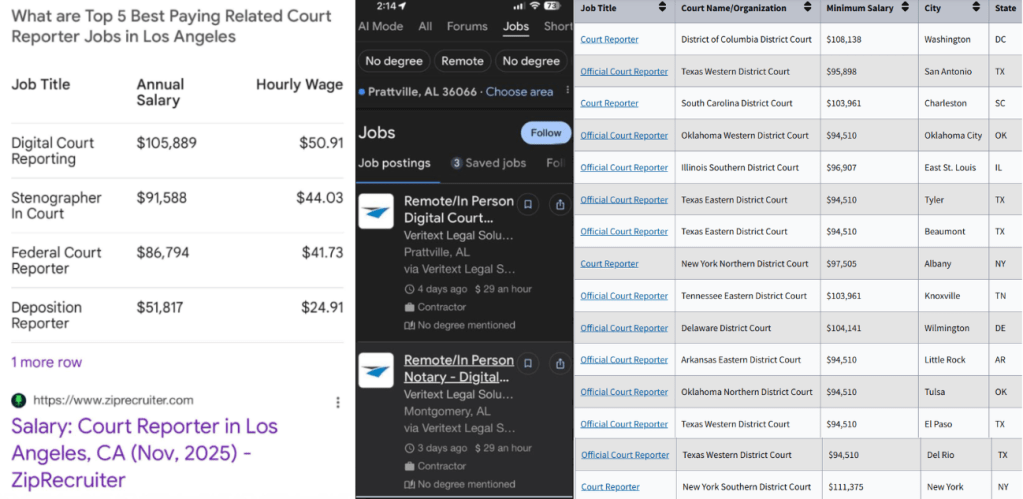

Meanwhile, the suggestion that federal court reporters in Los Angeles earn under $90,000 annually strains credibility. Federal reporters typically receive a salaried base that is augmented by transcript fees. In most metropolitan federal districts, total compensation routinely surpasses six figures. Even entry-level federal positions, especially in high-cost urban markets, exceed the figures presented in the viral post. The disparity between these claims and observable reality raises a critical question: who benefits from this narrative?

The answer may lie in the aggressive recruitment strategies of large national reporting agencies and legal services conglomerates. Companies that have invested heavily in digital-only infrastructures have a vested interest in promoting the perception that digital reporting is not only acceptable but preferable. By inflating wage claims, they create an illusion of upward mobility and financial security, enticing workers into roles that in practice often come with limited oversight, inconsistent workflow, and reduced professional recognition.

This dynamic is further complicated by the lack of transparency in how these wage figures are generated. Job aggregation sites scrape data from broad keyword pools, sometimes conflating job titles, regions, and responsibilities. An advertised hourly rate of $29 in a rural market can be algorithmically transformed into a Los Angeles average, despite no direct evidence to support such equivalence. A static 40-hour calculation is then applied to extrapolate an annual salary, ignoring overtime, per-page billing, and the structural differences between employee and independent contractor status.

The result is a wage mirage, one that undermines both public understanding and professional morale. It tells young entrants that the path of least resistance is not only viable but financially superior, while erasing the value of certification, training, and craftsmanship. It also sends a confusing message to attorneys and litigants, who may assume that choosing a digital reporter is a fiscally sound alternative, unaware of the hidden costs: delayed transcripts, higher error rates, lack of admissibility in certain jurisdictions, and potential ethical breaches.

Court reporting is not a commodity. It is a public trust function. The record produced today may determine the outcome of an appeal, the enforcement of a judgment, or the credibility of a witness. To reduce that responsibility to a race for the cheapest or supposedly highest-paid shortcut is to gamble with the integrity of the justice system.

There is also the matter of oversight. Stenographers operate under the scrutiny of licensing boards, professional associations, and court rules. Digital recording programs, especially those expanded during the pandemic, often operate in regulatory gray areas. While some jurisdictions permit digital recording under limited circumstances, the expansion of such practices into arenas where certified reporters are readily available raises significant ethical and legal concerns.

The irony is stark. At a time when artificial intelligence and automation are encroaching on nearly every profession, court reporting remains one of the few disciplines where human expertise, judgment, and accountability cannot be replicated by software alone. The claim that the least involved role in the process commands the highest wage is not a sign of progress. It is a symptom of systemic confusion.

What the viral graphic ultimately reveals is not a new economic hierarchy but a narrative failure. It exposes the growing gap between algorithmic storytelling and lived professional reality. It invites scrutiny of who writes these narratives, what data they use, and how such content shapes the decisions of workers, firms, and policymakers.

The court reporting profession deserves clarity, transparency, and respect. It deserves wage data that reflects not just averages but the complexity of its compensation structure. It deserves public understanding that the person who produces the official record is not ancillary but essential. And it deserves a future built on truth rather than trending misinformation.

Until such clarity prevails, every misleading graphic and inflated claim must be met with careful analysis and professional advocacy. The integrity of the record, and the livelihoods of those who safeguard it, depend on nothing less.

StenoImperium

Court Reporting. Unfiltered. Unafraid.

Disclaimer

“This article includes analysis and commentary based on observed events, public records, and legal statutes.”

The content of this post is intended for informational and discussion purposes only. All opinions expressed herein are those of the author and are based on publicly available information, industry standards, and good-faith concerns about nonprofit governance and professional ethics. No part of this article is intended to defame, accuse, or misrepresent any individual or organization. Readers are encouraged to verify facts independently and to engage constructively in dialogue about leadership, transparency, and accountability in the court reporting profession.

- The content on this blog represents the personal opinions, observations, and commentary of the author. It is intended for editorial and journalistic purposes and is protected under the First Amendment of the United States Constitution.

- Nothing here constitutes legal advice. Readers are encouraged to review the facts and form independent conclusions.

***To unsubscribe, just smash that UNSUBSCRIBE button below — yes, the one that’s universally glued to the bottom of every newsletter ever created. It’s basically the “Exit” sign of the email world. You can’t miss it. It looks like this (brace yourself for the excitement):