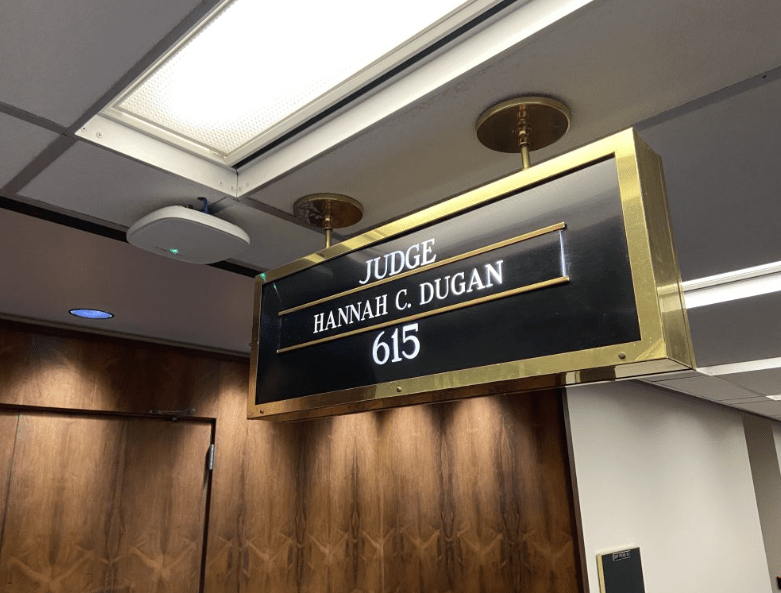

When jury selection begins next week in the federal obstruction case against Milwaukee County Circuit Court Judge Hannah Dugan, the proceedings will unfold under the shadow of a piece of evidence rarely seen in an American courtroom: an off-the-record audio recording captured inside her courtroom during a criminal calendar session. The recording—sealed from public release by state court administrators and disputed in detail by Dugan’s defense team—has already ignited a broader debate about transparency, judicial accountability, and the limits of what constitutes a “record” of judicial conduct.

Federal prosecutors allege that the audio captures moments in which Dugan improperly assisted an undocumented immigrant, a criminal defendant appearing before her, in avoiding arrest by federal immigration authorities. According to prosecutors, Dugan made statements indicating an intent to shield the defendant from detection or apprehension. Defense attorneys sharply dispute the characterization, arguing that the recording is being taken out of context and includes fragments of dialogue from times when Dugan was not even present in the courtroom.

The trial, scheduled to begin December 15 after two days of jury selection on the 11th and 12th, will mark a rare instance in which a sitting state judge stands trial for alleged obstruction arising from conduct on the bench. But the evidentiary dispute surrounding the recording has already drawn nearly as much attention as the charges themselves.

A Recording Not Intended as a Record

The recording at issue was made by courtroom audio equipment designed to capture the proceedings for internal use, including administrative review, staff reference, or later transcription of on-the-record hearings. Courts across the country routinely rely on such systems as backups to the work of court reporters or as supplements to digital recording systems in lower courts. But in Wisconsin—like many states—these audio feeds are not considered “verbatim records” unless they are made during officially convened proceedings with the intention of producing transcripts.

This distinction became central on November 29, when The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel submitted an open-records request seeking access to the recording. Wisconsin court officials denied the request, explaining that the audio was not a verbatim record of a court proceeding and therefore exempt from disclosure. Because the recording captured off-the-record discussion and internal courtroom communications, officials argued, releasing it could compromise the integrity of internal judicial operations and violate rules governing confidential conferences.

The decision immediately drew scrutiny. Open-government advocates called the refusal “legally thin,” noting that Wisconsin’s public records law favors transparency unless a specific exemption clearly applies. Critics argued that if the recording is reliable enough for use in federal court, it should be reliable enough for public inspection.

But supporters of the denial countered that the standard for public release is distinct from the standard for admissibility. A recording may be admissible as evidence—subject to authentication, relevance, and a judge’s discretion—while still falling outside the category of records that must be disclosed to the public.

Amid this debate, one underlying fact remains uncontested: the audio was never intended to be an official representation of what transpired in the courtroom that day. That reality complicates both the legal and ethical dimensions of the case.

Defense Fights to Limit Use of the Recording

Dugan’s defense team has filed a motion asking the trial judge to bar prosecutors from playing portions of the recording that include remarks made when Dugan was not physically present. According to the defense, the government seeks to introduce statements from lawyers, staff, or other individuals in the courtroom and attribute their context, tone, or implications to Dugan herself.

The motion describes the recording as “non-continuous,” containing moments of unclear audio, overlapping conversations, and periods in which the judge’s microphone was not activated. Defense counsel argues that introducing the recording without proper contextual safeguards could mislead jurors about what Dugan personally said or intended.

“Off-the-record discussions are, by their nature, informal and sometimes incomplete,” the defense wrote. “They are not designed to serve as transcripts, nor are they intended to be preserved or interpreted with the formality of sworn statements.”

Legal analysts note that this argument aligns with long-standing concerns about informal recordings in judicial settings. In many states, off-the-record discussions occur precisely because the law recognizes moments when judges and attorneys must speak candidly, confer about scheduling, or clarify procedural matters without creating a binding record. Whether federal prosecutors will be permitted to treat these moments as substantive evidence remains an open question.

As of Friday, the trial judge had not yet ruled on the motion.

Prosecutors Describe Recording as Crucial Evidence

Federal prosecutors, however, frame the recording as indispensable. They contend that Dugan’s intent can be inferred from her tone, her timing, and the surrounding events captured on the audio. The government alleges that Dugan took steps to ensure that a defendant known to be undocumented was released before federal agents stationed near the courthouse could detain him.

Although the exact content of the alleged statements remains under seal, prosecutors have hinted that they believe the recording demonstrates an “affirmative act” of obstruction—an element required to prove the charge.

The prosecution may also argue that by virtue of her position, Dugan understood the potential consequences of the timing and phrasing of her statements, and that she acted with knowledge of the pending federal interest in the defendant.

In the absence of a public copy of the audio, much of this remains speculative. But the mere claim that a judge’s off-the-record remarks could constitute a federal offense has triggered alarm within segments of the judiciary.

Transparency vs. Confidentiality

The dispute has raised complex questions about how courts define the boundaries of transparency. Open-government advocates argue that the public has a right to hear evidence that could influence the outcome of a high-profile federal trial involving a sitting judge. They note that accountability depends on public scrutiny, especially when the alleged conduct involves potential misuse of judicial authority.

But others warn that forcing disclosure of off-the-record audio could have unintended consequences. Judges, attorneys, and court staff routinely discuss scheduling, plea negotiations, interpreter issues, witness accommodations, and procedural complexities outside the official record. If such conversations were subject to release under open-records laws, many fear it would chill candid discussions and impair courtroom efficiency.

The debate has revived long-standing tensions between court reporters—whose work creates the only official verbatim record—and jurisdictions that increasingly rely on digital recording systems. Audio systems, originally implemented as backups or for administrative convenience, are now at risk of being treated as quasi-official records despite their limitations.

This trial, some experts predict, may become a cautionary tale for states that attempt to replace certified stenographic reporters with automated recording systems.

A Case With National Implications

Beyond the immediate questions of guilt or innocence, the Dugan trial may set important precedents for how off-the-record conversations are handled in future legal disputes.

If the trial judge rules that the disputed portions of the recording are admissible, it could signal a judicial willingness to treat informal audio—never intended for public or legal reliance—as probative evidence. Defense lawyers nationwide may respond by seeking clearer rules governing the confidentiality and limits of courtroom audio capture.

Conversely, if the court restricts the use of the recording or excludes portions of it, the ruling may underscore the judiciary’s commitment to protecting boundaries between official proceedings and informal discussions.

“It’s rare that the definition of a ‘record’ itself becomes the subject of litigation,” one former federal prosecutor noted. “This case forces the system to confront whether technology has blurred lines that statutes were never designed to address.”

What Comes Next

With jury selection looming, both sides are preparing for a trial that will likely be as much about the legal culture of courtroom operations as about the alleged conduct of Judge Dugan herself.

The trial is expected to draw significant media attention, not only for the charges but also for what it reveals about the evolving relationship between transparency, technology, and judicial ethics. Advocacy groups are already petitioning for greater access to administrative court audio, while judicial organizations prepare friend-of-the-court briefs warning against setting precedents that undermine judicial deliberation.

For now, the recording remains under seal, the defense motion remains pending, and the public must rely on filings, hearings, and the federal trial itself to understand what transpired in Judge Dugan’s courtroom.

But one thing is clear: the outcome of this case will reverberate far beyond Milwaukee. It will shape how courts nationwide think about the sanctity of the record, the reliability of digital audio, and the fragile, complicated line between what is said openly on the bench and what is meant to remain off the record.

StenoImperium

Court Reporting. Unfiltered. Unafraid.

Disclaimer

This article reflects my perspective and analysis as a court reporter and eyewitness. It is not legal advice, nor is it intended to substitute for the advice of an attorney.

This article includes analysis and commentary based on observed events, public records, and legal statutes.

The content of this post is intended for informational and discussion purposes only. All opinions expressed herein are those of the author and are based on publicly available information, industry standards, and good-faith concerns about nonprofit governance and professional ethics. No part of this article is intended to defame, accuse, or misrepresent any individual or organization. Readers are encouraged to verify facts independently and to engage constructively in dialogue about leadership, transparency, and accountability in the court reporting profession.

- The content on this blog represents the personal opinions, observations, and commentary of the author. It is intended for editorial and journalistic purposes and is protected under the First Amendment of the United States Constitution.

- Nothing here constitutes legal advice. Readers are encouraged to review the facts and form independent conclusions.

***To unsubscribe, just smash that UNSUBSCRIBE button below — yes, the one that’s universally glued to the bottom of every newsletter ever created. It’s basically the “Exit” sign of the email world. You can’t miss it. It looks like this (brace yourself for the excitement):