Recently, a veteran reporter reached out to me after reading one of my articles on rate negotiation. She shared a story that was both powerful and painful — one that highlighted not only her personal resilience but also the complicated terrain our profession faces when it comes to credentials, regulation, and value.

This reporter had decades of experience, multiple professional designations, and a deep love for her craft. She had weathered health battles and industry shifts, yet remained passionate about the work. Her message was filled with grit, warmth, and the unmistakable voice of someone who has seen this profession evolve over decades.

In her comments, she made a point that comes up often in court reporting circles: reporters with higher credentials should command higher rates. Many hold this view, especially those who have invested significant time and money to earn and maintain certifications from professional associations. On the surface, the logic seems straightforward — additional credentials should reflect higher skill, and higher skill should translate into higher pay.

But in the real-world regulatory and economic landscape of court reporting, that assumption is far less clear-cut.

The Problem with Credential Inflation

There’s no question that skill matters. Accuracy matters. Realtime capability matters. Speed and precision under pressure matter. These are the bedrock of our profession.

The problem isn’t with reporters who choose to pursue additional credentials. The problem is with the system that has elevated voluntary association designations into perceived markers of value — without ensuring those designations carry any regulatory weight or meaningful economic power.

Unlike professions such as law or engineering, court reporting operates under a patchwork of state licensing laws, voluntary association credentials, and minimal unified enforcement. The result is confusion, inconsistency, and a marketplace where credentials are marketed as elite signifiers but don’t reliably correspond to pay parity, legal authority, or professional protection.

For example, in California, national association certifications are not required to work as a realtime reporter in court or in depositions. Licensed Certified Shorthand Reporters (CSRs) routinely perform at 99.9% accuracy, producing exceptional realtime and transcripts without holding additional national credentials.

This doesn’t diminish the efforts of those who do earn them. But it raises a key question: if credentials aren’t legally required, don’t carry regulatory weight, and don’t guarantee higher pay — what are we really buying when we maintain them year after year?

A System That Hasn’t Kept Up

For decades, California’s per-page rates for official reporters were frozen at levels set in the 1970s. Until 2021, reporters were working at rates that hadn’t been adjusted for inflation in fifty years. Even after the long-overdue increase to $3.99 per page, the rate remains dramatically below what it would be if indexed to inflation — closer to $18 per page.

During that same period, the national professional association focused on collecting dues, requiring continuing education, hosting conventions, and maintaining credentialing systems. What it did not do was spearhead meaningful economic reform, build standardized enforcement across states, or push for structural change that would give those credentials real power.

Contrast that with how other professions have built durable regulatory frameworks.

Two Models That Work – Attorneys and Professional Engineers

Attorneys are licensed by their respective states under a protected title (Esquire/Attorney). State bar associations oversee licensure, investigate complaints, issue cease and desist orders to unlicensed individuals, and refer cases to state attorneys general or the Department of Justice when necessary. The title is legally protected, and misuse has real legal consequences.

Professional Engineers (P.E.s) use a different but equally strong model. Each state administers its own licensure exam and enforces professional standards, while the National Society of Professional Engineers provides consistency and support around the P.E. designation, which is standardized nationwide. States retain enforcement power, ensuring both a uniform title and meaningful regulatory teeth.

Court reporting has neither. We don’t have a standardized, legally protected title across states, nor do we have a unified state-based enforcement structure with real authority. Instead, voluntary association credentials have filled the gap — but they lack the legal weight and enforcement power that bar associations and state engineering boards wield.

Title Protection Without Teeth

California recently enacted a form of title protection for court reporters, but it’s largely symbolic. The Court Reporters Board (CRB) can issue cease and desist letters to individuals or entities misusing protected titles — but only if those individuals or entities are already under the Board’s jurisdiction (i.e., licensed CSRs or registered agencies).

If someone operates entirely outside the licensing system, the CRB won’t act. There’s no meaningful mechanism for broader enforcement, no referral to the attorney general, and no penalties with real bite.

In other words, we have title protection in name only. Without strong, state-level enforcement authority that extends beyond licensees, the protection is effectively hollow.

Where NCRA Credentials Carry Legal Weight — and Where They Don’t

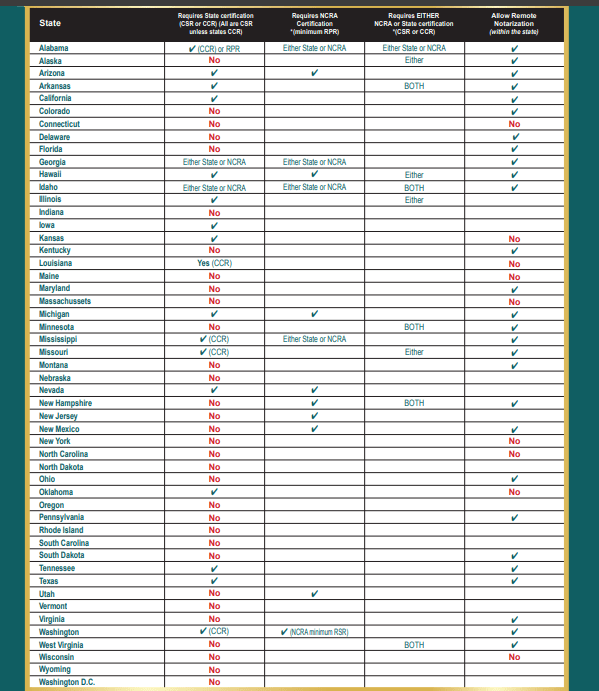

It’s worth noting that in eight states, NCRA credentials are accepted as part of state licensure requirements. In these jurisdictions, reporters can qualify by holding specific NCRA certifications (typically RPR or higher), either in lieu of a state-administered test or as one of two acceptable pathways.

But this is the exception, not the rule. Even in those states, it’s not NCRA granting a license — it’s the state choosing to recognize the credential within its regulatory framework. The power still rests entirely with the state’s licensing authority.

Outside of those eight states, NCRA credentials are voluntary and carry no independent regulatory weight. They may be valued by employers or agencies, but they don’t confer legal authority to work. In places like California, for example, NCRA certifications are not required to practice, and licensure is governed solely by state law.

This fragmented approach contributes to the confusion. Reporters sometimes believe NCRA credentials are universally “required” or legally meaningful, when in reality, they only have regulatory force where a state has explicitly chosen to adopt them.

When High Prices Meet Market Pressure

One growing concern is how attorneys are increasingly vocal about the “high cost” of court reporting. As budgets tighten and more firms look for ways to cut expenses, there’s a real risk that highly skilled, credentialed reporters who charge appropriately for their value could lose work to cheaper alternatives.

Price pressure doesn’t just affect the low end of the market — it can squeeze out the very reporters who deliver the most consistent, high-quality work.

I’m reminded of a colleague who built a thriving career doing international work in Europe. For years, he traveled extensively, working in Amsterdam and across the continent, commanding premium rates that reflected both his skill and the costs of being on site for international proceedings.

When COVID hit and proceedings shifted to remote, his niche vanished almost overnight. He was replaced by U.S. reporters willing to work remotely at significantly lower rates, eliminating the need for travel and specialized arrangements. Within months, his once-stable international practice had dried up. Ultimately, he left the profession entirely and transitioned to a career in software engineering.

It’s a stark reminder: even the most skilled and credentialed reporters are not immune to market dynamics. If the legal community views rates as “too high” and finds others willing to work for less — even at lower skill levels — work can shift rapidly. That makes unified, state-based licensing, standardized titles, and consistent economic advocacy even more critical to avoid a race to the bottom.

The Credential Pay Gap

Because these credentials are voluntary and not legally required, their impact on pay varies widely. In some regions, holding a certain designation might yield modest rate advantages. In others, it makes no difference at all. And in many cases, agencies quietly keep credentialed reporters at lower rates simply because no one is advocating for change on their behalf.

I’ve personally seen reporters with advanced credentials charging well below market value for years because they never raised their rates — and no regulatory structure existed to standardize or enforce fair compensation. When some eventually negotiated modest increases, agencies accepted them without hesitation. That’s telling.

This is not a system that rewards credentials consistently or systematically. It’s a fragmented marketplace where individual reporters are left to negotiate alone — often undercutting one another in the process.

Skill Is Measurable — Credentials Are Optional

My position is simple: I don’t hold certain national credentials, and I don’t need to in order to perform at the highest level in California. My realtime accuracy is 99.9%, and my work speaks for itself. I respect those who choose to pursue credentials, but I reject the notion that letters after a name should dictate rates — especially in a state that doesn’t require them.

Skill is measurable. Accuracy is measurable. Consistency is measurable. Whether someone has chosen to invest thousands in association memberships, conventions, and CEUs does not automatically make their work more valuable than that of a highly skilled, licensed reporter who has not.

The real issue isn’t credentials. It’s the absence of a unified, enforceable, state-based regulatory structure that standardizes titles and backs them with legal authority.

A Better Model – State Licensure + Standardized Title

Imagine a system where every state has its own licensure exam and enforcement authority, but the professional title is standardized nationwide.

Each state would license and regulate reporters, ensuring only qualified individuals could use the protected title. A national body could support consistency, but enforcement would remain at the state level. Unauthorized use of the title would result in cease and desist orders and, if necessary, legal action — just as it does for attorneys and engineers.

In such a system, voluntary association credentials could still exist, but they would be supplementary, not foundational. The baseline would be state licensure, standardized title, and real enforcement — exactly what our profession lacks today.

Negotiation, Value, and Professional Identity

This entire conversation ties back to rate negotiation.

Too often, reporters conflate “negotiating” with “lowering rates.” But true negotiation is about advocating for value, not discounting it. Whether credentialed or not, reporters should stand firm on published, consistent rates that reflect their skill, responsibility, and legal role.

Credentialed reporters who undercharge harm themselves and the profession. Non-credentialed reporters who deliver elite work should not be undervalued. The real dividing line is not who has which letters — it’s who upholds professional standards, delivers excellence, and refuses to undercut the market.

A Personal Note

The reporter who wrote to me reminded me why this profession matters. Even in the face of serious health challenges, she was working, advocating, and standing her ground. Her story reflects the resilience and commitment that have kept this profession alive through decades of change — often without the structural support it deserves.

We owe it to ourselves and to future generations to build systems worthy of that dedication. That means moving beyond credential marketing toward state-based licensing, standardized titles, real enforcement, and fair economic structures.

Until then, credentials will remain optional adornments in a fractured system, not the foundation of professional identity and value.

Redefining Professional Power

Credentials have their place, and reporters who pursue them deserve respect for their efforts. But credentials are no substitute for robust state licensure, standardized professional identity, and real enforcement power.

Our rates should reflect skill, responsibility, and consistency — not voluntary designations. And our regulatory framework should mirror those of other respected professions, where titles are protected, states hold authority, and national consistency supports—not replaces—enforcement.

The future of court reporting depends on more than letters after our names. It depends on building a structure that recognizes, protects, and enforces the true value of what we do.

StenoImperium

Court Reporting. Unfiltered. Unafraid.

Disclaimer

“This article includes analysis and commentary based on observed events, public records, and legal statutes.”

The content of this post is intended for informational and discussion purposes only. All opinions expressed herein are those of the author and are based on publicly available information, industry standards, and good-faith concerns about nonprofit governance and professional ethics. No part of this article is intended to defame, accuse, or misrepresent any individual or organization. Readers are encouraged to verify facts independently and to engage constructively in dialogue about leadership, transparency, and accountability in the court reporting profession.

- The content on this blog represents the personal opinions, observations, and commentary of the author. It is intended for editorial and journalistic purposes and is protected under the First Amendment of the United States Constitution.

- Nothing here constitutes legal advice. Readers are encouraged to review the facts and form independent conclusions.

***To unsubscribe, just smash that UNSUBSCRIBE button below — yes, the one that’s universally glued to the bottom of every newsletter ever created. It’s basically the “Exit” sign of the email world. You can’t miss it. It looks like this (brace yourself for the excitement):