In response to our recent article, “When ‘No Options’ Isn’t an Option: The Quiet Collapse of Court Reporting in West Texas,” a well-intentioned reader offered the following comment:

“There is an entire national organization of certified digital reporters, i.e., not recorders, named AAERT—the American Association of Electronic Reporters and Transcribers at aaert.org. Peruse the website of ethics, bylaws, policies and procedures, testing protocol with the Best Practices Guide of 285 pages, from which the test is administered, which must be mastered to pass the test. So if you are having court reporter shortages, you may wish to investigate this opportunity that has been around since 1985. They may be able to help with your backlog.”

This is a common suggestion being repeated across the country—especially by those seeking short-term fixes to a long-term crisis. But the suggestion deserves a deeper look, because while it sounds like a helpful workaround, it misses the core issue and carries long-term risks that many in the legal field don’t fully understand.

The Heart of the Problem is the Court Reporter Shortage

No one denies that we are facing severe shortages of certified court reporters in many parts of the country. Courts in rural areas, like West Texas, are struggling to find enough stenographers to keep up with demand. Retirements are accelerating. Job openings are going unfilled.

But just because there’s a shortage doesn’t mean any available substitute will do.

This isn’t a matter of just finding someone to “take notes” or “record audio.” It’s about protecting the accuracy, integrity, and legal credibility of the official court record. And not all reporting methods are created equal.

AAERT and Digital Reporters – What They Do (and Don’t Do)

AAERT—the American Association of Electronic Reporters and Transcribers—has been around since 1985 and offers certification for digital court reporters and transcribers. Their members typically operate recording equipment in courtrooms, monitor proceedings, and then transcribe the audio later. Their website offers a code of ethics, best practices guide, and a 285-page study manual.

That all sounds reassuring on the surface—but here’s where the fundamental differences emerge:

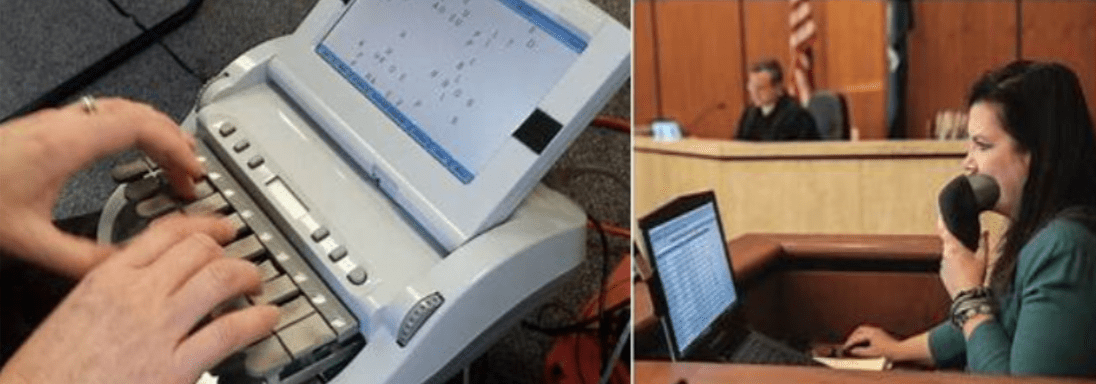

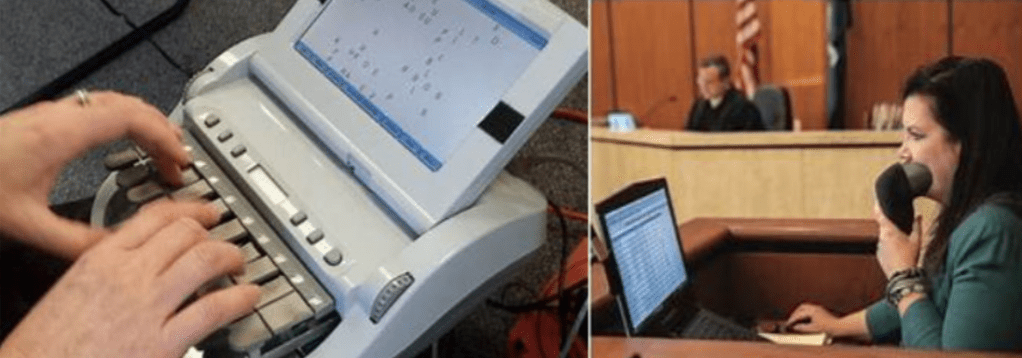

- AAERT “reporters” are not live, realtime professionals.

They operate equipment. They don’t produce realtime transcripts. They don’t interrupt to ask for clarification. They don’t capture the record verbatim as it’s happening. - There’s no legal certification of accuracy at the moment the record is made.

With a stenographer, the record is created live, by a licensed, sworn officer of the court. The person who creates the record is the one certifying its accuracy—right then and there. With digital recording, that chain of custody is broken. The audio is captured by one person, often transcribed by another, and then certified post hoc—if at all. - They are not trained to the same standards as certified court reporters.

A 285-page study guide may sound impressive, but it pales in comparison to the 2–4 years of schooling, 225 WPM testing requirements, realtime captioning expertise, and state/national licensing that stenographic reporters must complete to earn their title.

We Aren’t Facing a Tech Problem. We’re Facing a Prioritization Problem.

The commenter’s suggestion is based on a common (and dangerous) assumption: that this crisis is about tools. It’s not.

It’s about value.

Court reporting is being deprioritized by budget-conscious administrators and policy makers who don’t realize the long-term implications of replacing skilled professionals with machines and post-processors. They’re being sold a narrative that something is better than nothing—when in reality, substandard records can do more harm than good.

Judges and attorneys still overwhelmingly want live, certified reporters in their courtrooms. But they aren’t always aware how close the profession is to collapse—and they often don’t understand that once stenographic infrastructure disappears, it’s gone for good.

We can’t “pause” court reporting and pick it up again later. We can’t let schools close, manufacturers go under, and software companies fold—and then expect to reboot the entire ecosystem if AI or digital recording fails to deliver.

A Chain of Custody You Can’t Afford to Break

Legal records are only as strong as the system that creates them.

With a court reporter:

- The record is created and certified in real time.

- The reporter is trained to handle interruptions, overlapping voices, difficult terminology, and non-verbal cues.

- The integrity of the record is protected from the moment of capture.

With digital systems:

- Audio may be unclear, corrupted, or incomplete.

- The person transcribing the record might not have been present.

- Edits, omissions, or misattributions can go unnoticed—until it’s too late.

Let’s be honest: an audio recording is not a transcript. And a machine that records without context cannot deliver the same accountability or accuracy as a trained human expert.

So What Should We Be Doing?

Instead of pivoting to alternatives that weaken the legal record, we need to double down on preserving—and investing in—the profession that works.

Here’s how:

- Fund and support stenographic schools. Many programs are full and thriving. Voicewriting is helping fill gaps quickly. The pipeline is there—but it needs backing.

- Retain and reward working reporters. Raise rates, offer bonuses, and create incentives for certified reporters to work in rural areas or underserved courts.

- Educate the legal community. Judges, clerks, and attorneys need to understand that not all “reporters” are created equal—and that realtime, certified professionals offer irreplaceable value.

- Redirect funding toward sustainable solutions. Instead of spending millions building digital infrastructure, reinvest in training and keeping the gold-standard method alive.

This Isn’t About Gatekeeping. It’s About Standards.

We’re not dismissing the efforts of those certified by AAERT or those who operate digital systems with care and professionalism. But let’s not confuse accessibility with equivalence.

Digital recording may fill gaps in an emergency. But it’s not a replacement for the work of a licensed, realtime court reporter—nor should it be treated as one.

So, to answer the original question: yes, we’ve heard of AAERT. But we also know what’s at stake. If the legal system truly wants to protect the integrity of the record, we can’t afford to lower the standard.

We must protect, fund, and grow the profession that has served the justice system for over a century—before we replace it with something that simply sounds like a solution.

Disclaimer

The content of this post is intended for informational and discussion purposes only. All opinions expressed herein are those of the author and are based on publicly available information, industry standards, and good-faith concerns about nonprofit governance and professional ethics. No part of this article is intended to defame, accuse, or misrepresent any individual or organization. Readers are encouraged to verify facts independently and to engage constructively in dialogue about leadership, transparency, and accountability in the court reporting profession.

- The content on this blog represents the personal opinions, observations, and commentary of the author. It is intended for editorial and journalistic purposes and is protected under the First Amendment of the United States Constitution.

- Nothing here constitutes legal advice. Readers are encouraged to review the facts and form independent conclusions.

***To unsubscribe, just smash that UNSUBSCRIBE button below — yes, the one that’s universally glued to the bottom of every newsletter ever created. It’s basically the “Exit” sign of the email world. You can’t miss it. It looks like this (brace yourself for the excitement):