In the heart of our judicial system, there exists a quiet crisis—one that is rarely acknowledged, yet deeply felt by the professionals who ensure an accurate record of every word spoken in court: the pro tempore court reporters. These highly skilled stenographers, many of whom are women, are facing increasing discrimination not for the quality of their work, but for the perceived size of their paychecks.

The Misunderstood Economics of the Profession

To the untrained eye—particularly that of some judges, clerks, and attorneys—a court reporter’s invoice can seem exorbitant. A $5,000 daily bill for a trial with expedited transcripts transcripts and per diems and realtime services may raise eyebrows, especially in post-verdict motions to tax costs where such expenses are scrutinized. However, this figure is wildly misleading and reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of how court reporters are paid.

These invoices are not direct payments to the reporters. Rather, they are billed through agencies—third-party businesses that often take 50% or more of the total fee right off the top. The reporter, who actually sits in court for hours and then spends additional time meticulously preparing the transcript, walks away with only a fraction of what’s billed. If a reporter invoices $300,000 over a year, their actual take-home income is closer to $100,000—after agency cuts, subcontractor payments, and significant business expenses.

Hidden Costs – Subcontractors and Equipment

Producing a verbatim transcript of a trial isn’t a solo act. Reporters often hire scopists and proofreaders—skilled professionals who help refine and perfect the final product. Scopists alone may charge $3.00 per page, which on a full trial day could amount to $600 or more. This cost is borne by the reporter, not the agency.

On top of that, court reporters must maintain their own equipment and software. A professional stenographic machine costs upwards of $5,000. So does the Computer-Aided Transcription (CAT) software essential to converting steno notes into readable transcripts. Add to that other business expenses—insurance, continuing education, internet services, office supplies—and it becomes clear that these professionals are entrepreneurs, not court employees, bearing all the financial risk with none of the job security.

A Disguised Form of Gender Bias

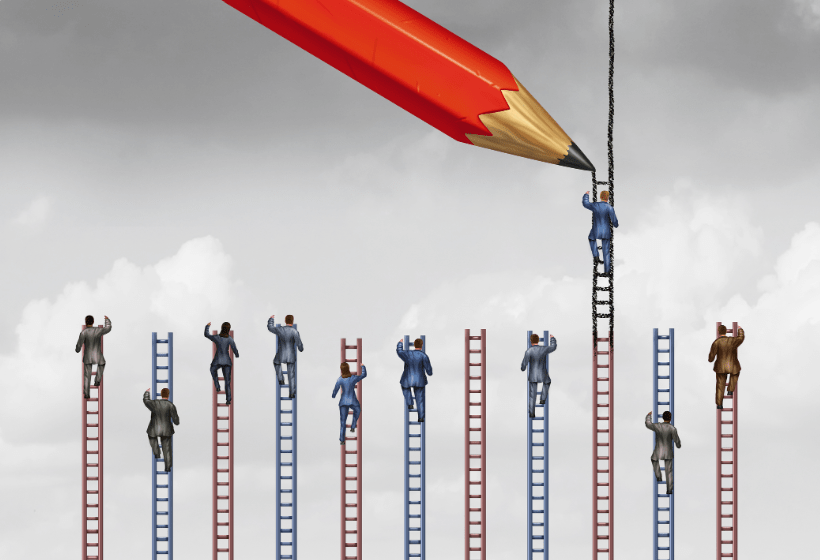

What compounds the issue is the undercurrent of gender discrimination cloaked in economic judgment. Court reporting has traditionally been a female-dominated field, while judges and attorneys have historically been predominantly male. When male judges or attorneys see a $5,000 invoice from a woman, there’s an implicit message: She shouldn’t be making more than I do.

This resentment isn’t just internal—it manifests in daily microaggressions and overt hostility. Reporters are often ignored during courtroom introductions, their presence and role diminished to invisibility. Judges routinely refuse to slow down their speech, even after multiple polite requests, making the job unnecessarily difficult. Clerks enforce abrupt, inflexible shutdowns at 4:30 p.m. sharp, giving reporters just two minutes to pack up expensive and sensitive equipment. Lunch breaks become a scramble as court reporters are shooed out the door the moment the bell rings, with no regard for the time or care required to secure their setup.

This disrespect isn’t simply bad manners. It’s symptomatic of a broader systemic bias—an economic and gender-based devaluation of the reporter’s role and labor.

Stagnant Statutory Rates – A 50-Year Disparity

Adding insult to injury, the statutory rates for transcripts remain stuck in a time warp. In 1970, the going rate was $3.00 per page. Today, in many jurisdictions, it’s only $3.99 per page. Adjusted for inflation, that 1970 rate should be nearly $18 per page in 2025 dollars. That means court reporters are making less, not more, than they were half a century ago—despite exponential increases in the cost of living, doing business, and technological demands.

How is it that the backbone of the judicial record-keeping process is expected to carry on with outdated compensation, all while being accused of overcharging?

The Reality of Freelance Court Life

Unlike salaried government employees, pro tempore reporters do not receive pensions, health benefits, or paid time off. They aren’t guaranteed work every day, with cancellations wreaking havoc on predictable income. A two-week trial can be canceled the night before, leaving a gaping hole in a reporter’s monthly revenue without any compensation for the lost opportunity.

Despite all of this, the professionalism and precision demanded of them never waver. They are expected to produce perfect transcripts under immense time pressure and with no room for error—while absorbing emotional exhaustion from hearing difficult cases and enduring physical fatigue from long hours seated in courtrooms.

Mastering the Craft – Decades of Dedication

The work court reporters perform—especially realtime reporting during trials—is not a skill that can be learned overnight. It takes years of rigorous training just to become certified, and over a decade of hands-on courtroom experience to provide high-quality realtime services, where the spoken word is transcribed and displayed in real-time with near-perfect accuracy. True mastery can take upwards of 20 years. This is a highly specialized, mentally and physically demanding profession that requires intense focus, linguistic expertise, and the ability to process multiple conversations at once—often in chaotic, high-stakes environments. The level of concentration and technical skill required is akin to that of concert pianists or air traffic controllers. And yet, despite the immense dedication it takes to reach this level, court reporters are too often treated as expendable or replaceable, rather than as the uniquely skilled professionals they are.

Time for Judicial Accountability

It’s time for the judicial system to recognize the vital role of court reporters and to correct the economic and gender biases that plague the profession. Judges must be educated on the actual economics behind reporter invoices. Clerks must be trained to treat court reporters with the same courtesy and respect given to other court staff. Attorneys should acknowledge the importance of an accurate record and advocate for fair treatment of those who provide it.

And most importantly, statutory rates must be revisited. If we value the integrity of the legal process, then we must properly compensate those who protect it.

The Unseen Guardians of the Record

Court reporters are not overpaid. They are overworked, underappreciated, and often misunderstood. Their invoices are not reflections of individual greed, but of a system that allows third-party agencies to exploit their labor, all while judges and attorneys cast judgment based on flawed assumptions.

Let us not continue to penalize these professionals for the illusion of wealth when in truth, they are fighting to survive in a broken system. Let us instead advocate for a judiciary that honors the contributions of court reporters—financially, professionally, and personally.

It’s time to bring this conversation out of the shadows and into the courtroom, where justice begins with the record—and the record begins with them.