The case involved 20 plaintiffs who alleged that their medical injuries and adverse health conditions resulted from exposure to hazardous and/or toxic substances caused by the eight named defendants. The defense counsel, though an exceptional toxic tort attorney, lacked experience in medical malpractice, leading to some amusing mispronunciations of medical terms. The jury struggled to endure the monotonous reading of the stipulation, with one juror even raising his hand to request a break, commenting on the dryness of the proceedings. If the jury found it challenging, the court reporter’s task was even more daunting—attempting to follow along with the error-ridden document displayed on the monitor while simultaneously correcting punctuation and spelling in real-time.

During a break, I attempted to get counsel to stipulate that I wouldn’t have to report the 22-page stipulation document he was reading from, but, unfortunately, since it was a factual document, it had to be part of the official record. So, I did what I could—I asked the attorney to slow down. I explained that I was writing in all the necessary punctuation on my machine, which required significantly more strokes than just transcribing his spoken words. I didn’t mention it, but I was also hoping to prevent my brand-new scopist from quitting. I should have asked the attorney to stop speaking punctuation altogether—something I find particularly frustrating—but he was already dismissive about my request. He even brought up to the judge the fact that I had requested that he slow down, as if reading the stipulation faster would somehow alleviate the jury’s suffering. However, my request ensured that the daily transcript could still be delivered on time. Attorneys often underestimate how much extra work they create for court reporters.

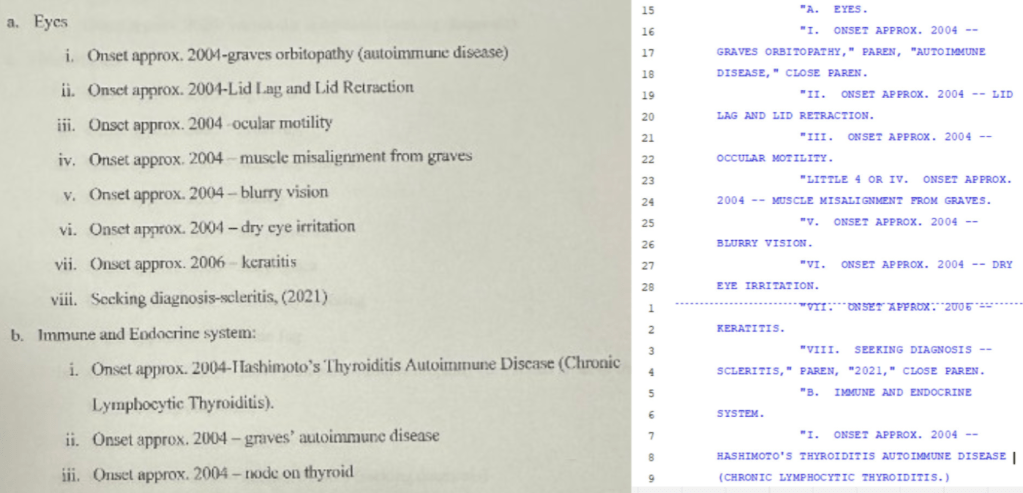

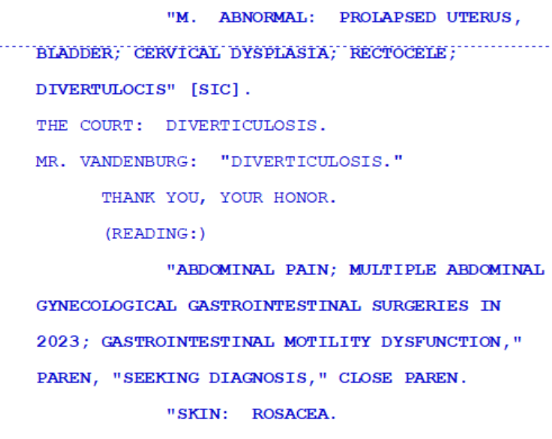

When attorneys misread documents, I make sure not to quote the incorrect portions. Instead, I end the quote before the misread word and resume quoting afterward to ensure accuracy. If an attorney mispronounces a term and is corrected, I transcribe the incorrect pronunciation with a [sic] notation to clarify why the correction was made. Similarly, if an attorney interrupts themselves mid-word, I use a dash to indicate the break before writing the full term correctly. Numbers are handled the same way—for example, “In 2020- — 2024″—to reflect what was intended, rather than what was partially spoken. If the attorney never corrects the misspoken word, then you would end the quote before the word (seeking) and start it after that word. So for example: “K. Onset 04-2024:” Seeking “acupuncturist weekly.”

And the “paren” is not in the quoted material, so we have to remove the quotes around all his speaking punctuations. That’s why I hate speaking punctuations.

Here’s another one. When he totally mispronounces something and someone corrects him, I must put in the word the way he pronounced it and [sic] so it’s clear why he was being corrected.

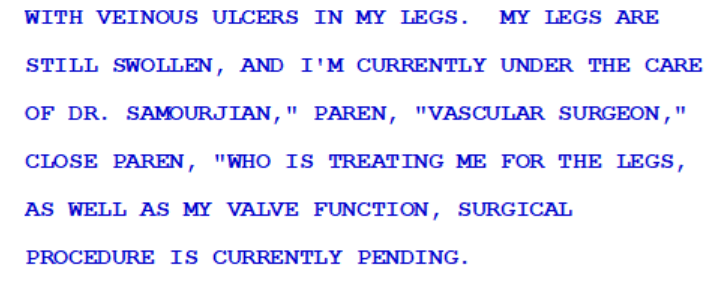

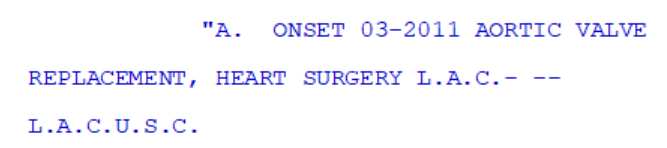

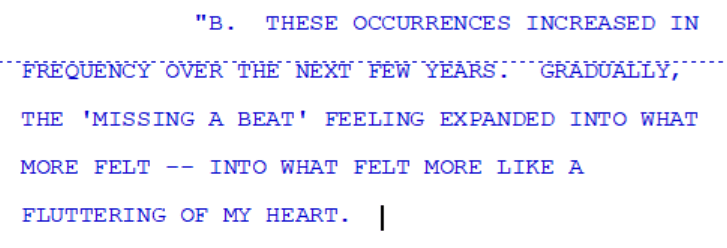

Here’s another one. If he stops short of saying the whole word, I dash it. So here, the full word was LACUSC, but he only said the LAC and interrupted, so it’s LAC- — and then the full word. Same with numbers. For example, “In 2020- — 2024.” If they meant to say 2024, but they interrupted, to leave it as 2020 wouldn’t be accurate because they meant 2024, but didn’t get to the -4, but did say 20.

Everything he reads is in quotes, so if he quotes something within those quotes, use the single quote, not the double quote:

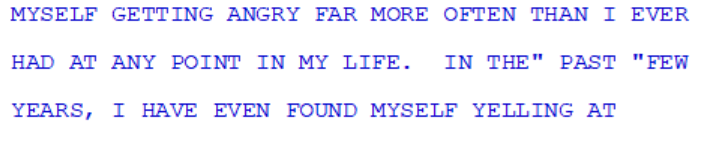

Here’s another one where he said “past,” but the transcript said “last” – so we don’t quote the “Past” in this section of quoted material:

If he says a word then pauses and starts over saying the word again, unquote and then quote again:

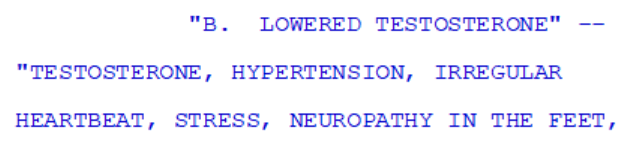

His misrepresentations and multiple attempts at pronouncing the word:

Proper punctuation is crucial, especially within quoted material. If something is quoted within a larger quotation, I use single quotes instead of double. If an attorney starts a word, pauses, and then repeats it, I close and reopen the quotation marks accordingly. Mispronunciations that resemble common variations (like “potato/potatoe”) are transcribed correctly, but if multiple incorrect attempts are made and a correction follows, I include the mispronunciations to provide clarity.

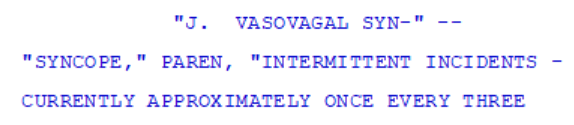

Like this one, the document had the opening paren in the transcript, but the attorney didn’t say the closing paren. That’s okay to leave off the closing paren in our transcript. If he had not said the opening “paren,” then I would have been able to put BOTH () symbols, but he said one and not the other. He should say both or don’t say it at all. But don’t mix/match with one verbal punctuation and then the punctuation. Same with if he had said “quote” without the “unquote.” It woud be: Ms. Jones said, quote, don’t do that. And then the kids stopped climbing the fence. But you wouldn’t do it this way, for example: Ms. Jones said, quote, don’t do that. And then the kids stopped climbing the fence.”

The written document we followed was riddled with punctuation errors, but our job as court reporters is not to transcribe it verbatim from the document. we must ensure the record is punctuated correctly, regardless of the errors in the original. For instance, if the transcript incorrectly included a hyphen, I omitted it. If the attorney verbally said “paren,” but only one bracket, I reflected that accurately, rather than forcing symmetry. Similarly, if they said “quote,” but never “unquote,” I followed the spoken words, rather than the erroneous document formatting.

Ultimately, this trial was not for an amateur reporter—three had already dropped out before me. However, the complexity and challenges are why I’m compensated well for my expertise. Despite the frustrating moments, the satisfaction of producing a meticulous and accurate record makes it all worthwhile.