Introduction

The legal services industry, like many others, is experiencing a seismic shift in response to the digital age. Traditional practices are being disrupted, and nowhere is this transformation more apparent than in the field of court reporting. Presently, court reporters, skilled individuals trained to capture the spoken word and transcribe legal proceedings, are indispensable fixtures in courtrooms and legal proceedings. However, today, a new contender has emerged on the scene: digital audio recording and transcription services.

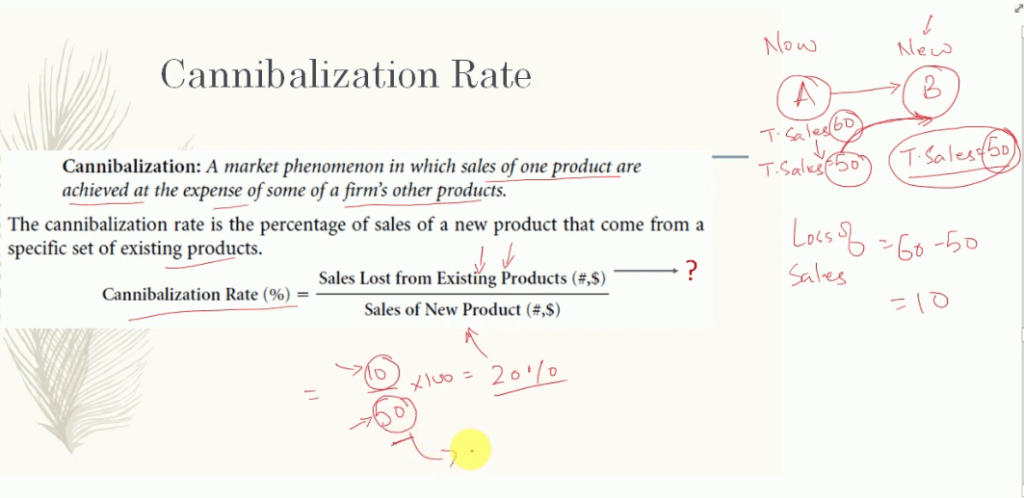

This article delves into the phenomenon of corporate market cannibalization within the court reporting industry, a term that refers to established entities consuming their own traditional market by adopting and promoting innovative, often digital, solutions that render their own services redundant. As we journey through this attempted digital transformation, we will discuss the disadvantages of this shift, including the false-marketing of cost savings and enhanced accessibility, and the disastrous mismanagement of transcriptionists in maintaining quality and accuracy in the court reporting industry.

While this shift presents various challenges and potential pitfalls, it is essential to critically examine its implications for the industry. We’ll explore the evolution of court reporting, the use of digital technology, and the rapid and growing trend of replacing court reporters with digital audio recording, videographers, and transcriptionists.

The article will also discuss the disastrous outcome of this shift on the American Judicial system, as well as the possible extinction of human stenographers and the impact that would have on the protection of the record. This transition is fraught with legal and ethical challenges, raising questions about privacy, data security, and potential errors in transcripts. To guide our exploration, we’ll provide real-world case studies and a comprehensive FAQ section to address common queries about the future of court reporting in the digital age.

The winds of change are blowing through the court reporting industry, and it’s crucial to understand the dynamics of this revolution, the implications for stakeholders, and the path forward in this shifting landscape.

There is nothing new about corporate cannibalization. It’s been occurring for hundreds, if not thousands, of years, in many industries. Especially prevalent in the technology world is Product cannibalism, where a company launches a new product into the market when it already has an existing product, so the new product ends up competing with their existing product. We see this a lot with printers. Companies must continually introduce new products to keep from losing future business to competitors. It’s a necessary evil.

There are two types of transitions, otherwise known as cannibalism. A constructive transition, or constructive cannibalism, and destructive cannibalism. Constructive cannibalism results in greater overall top-line revenue and bottom-line profit, whereas, destructive transitions results in the older-generation sales declining faster than the new-generation growth.

Our court reporting agencies are concerned that if they’re slow to adopt and innovate, their competitors will do it instead, so we are seeing a mass adoption of digital recorders in our industry. Politics in our industry is taking sides with the legacy service providers putting up a fight and boycotting any agency who adopts digital recording. The courts are taking the side of the legacy reporters and are rejecting transcripts that are not certified by a legacy, professional shorthand reporter.

The Evolution of Court Reporting Court reporting has a rich history that dates back centuries. Traditionally, it involved the presence of a skilled human court reporter who meticulously recorded every spoken word and action during legal proceedings. These professionals were trained to be accurate, impartial, and efficient in their work.

In the early days, court reporters relied on shorthand, a method of writing quickly in a specialized script, to capture spoken words. This process required immense skill and concentration. The transcribed records were vital for legal proceedings, serving as the official documentation of cases and trials.

As time went on, technology began to play a more prominent role in court reporting. The introduction of stenography machines in the late 19th century revolutionized the field. Stenographers used these machines to record proceedings phonetically, allowing for faster transcription. This technological leap significantly increased the efficiency and accuracy of court reporting.

Fast forward to the late 20th century, and the court reporting profession saw another transformation with the advent of computer-aided transcription (CAT) software. This software allowed court reporters to type directly into a stenotype machine, which translated their keystrokes into readable text in real-time. This innovation improved the speed at which transcripts could be produced and made it easier to edit and format the text.

In early 2000, the CAT software companies added a feature allowing court reporters to audio record proceedings where they could scope (edit) their transcripts that were synced to the audio recording using hot keys or hyper keys to rapidly navigate through the transcript and listen to audio at any given point, enabling them to instantly fix errors and make transcripts 100% accurate. Then the hardware manufacturers added a new feature to the stenographic machines, allowing them to record and playback right from the stenographic machine. So court reporters could unplug their machines from their laptop and go into chambers, never losing a recording of the proceedings. The steno machines make its own recording of the proceedings, so now there’s two independent audio recordings: one on the laptop and one on the machine writer. So court reporters could have five backups of every proceeding, and six if you add the instantaneous backup of all files to the cloud. All of this improved the security and protection of the record, ensuring nothing would be lost in case of a catastrophic machine failure, and it improved the accuracy from the 96.5% passing test rate without audio aides, to be able to achieve 100% accuracy on every transcript.

In 2003, Stenograph released the first paperless machine, an Elan Mira, then in 2009, a Diamante, which featured a color flat-panel display, two SD cards, two USB ports, microphone and headset jacks for AudioSync, and optional Bluetooth or WiFi realtime translation. How is that for high tech. Unfortunately, Hollywood is still obsessed with our paper writers. And some digital recorder companies show pictures of typewriters in their ads, instead of steno machines, going back in time even further. The 2003 Elan Mira is still more advanced and reflective of the “digital era” than the electronic recording hoax being shoved down the throats of the legal industry in 2024. The perpetrators of this new “digital recording” takeover would take us back in time to the 1800’s, but they think it would make them rich, so who cares what laws they’re breaking.

While these advancements enhanced the efficiency of court reporting, they were kept quiet by the professionals who used these tools, because the audio was deemed a work product, not to be delivered into the hands of the public. The printed transcript with the reporters’ certificate was the end product and what was admissible in court, not the audio recording. If a reporter were to hand over a recording, it would be necessary to listen to the entire audio and remove any off-the-record conversations that may have occurred. Many reporters never listen to the entire audio file; they just used it to spot check areas for names or troublesome areas for punctuation, if they even listen to it at all. Most use the audio as a backup only and never need to use the backup file. Court reporters aren’t trained to use audio editing software that would be used to edit the audio to remove off-the-record discussions. This could add hours and hours to an already long day of sitting in court or at depos and then creating transcripts at night or on weekends. It would also require additional hours of training on audio editing software. And it would increase the cost, which the market does not wish to bear.

Court reporters also personally invest in high-end equipment as their cost of doing business. They have high-quality, high-gain, noise canceling, multi-directional recording microphones and high-end noise-canceling headphones equipment where they could hear a pin drop.

This concept that we’re entering some kind of new digital age with an emergence of digital audio recording technology is laughable. It’s been around and utilized in the court reporting profession for several decades by highly skilled and certified professionals. What is new is that courts have been installing electronic recording equipment in lower courts, such as traffic, for the last 20 years so that they could save the cost of having court reporters in those departments. The courts spend millions on the recording equipment that has to be renewed every several years, costing millions more. Courts would save millions by employing court reporters in all departments to do the recording and archiving of all court recordings that they do anyway.

Maybe the fact that court reporters kept this capability a highly-guarded trade secret was a disservice to the courts who made decisions to record proceedings themselves and investing in all the equipment, and then training personnel to do the recordings, and IT to build the software to archive it all, and buying servers to archive it. Then they send the audio out to third parties to have it transcribed by uncertified, inexperienced, low-wage individuals, often two or more individuals on the same transcript, who are located outside the U.S. It could have saved the court billions over the decades that they’ve been doing it themselves, collectively, nationwide, to just let the official reporters foot the bill as they have been doing all along, unnoticed and unappreciated by the court administrators.

Another new development is the push by big box agencies in our industry to position themselves as the responsible charge for the record, “training anyone off the street,” as Anir Dutta, CEO of Stenograph, described it, to record their legal proceedings, and hiring cheap transcriptionists to produce the transcript, and cutting out the largest cost of services, the court reporters themselves. They’re using Automated Speech Recognition (ASR) software to produce the transcript from audio recordings, and then hiring scopists to clean it up using Microsoft Word software to edit the transcript. This move by the big boxes has opened Pandora’s box to vultures, outliers, and outsiders to come into our industry like the Wild West and Gold Rush phenomenon where everyone is wanting to get rich quick by recording legal proceedings themselves and charging what court reporters charge.

Our long-time trusted CAT software and machine hardware vendors are getting in on it too, creating ASR software for these new untrained, uncertified, persons off the street so they can simply set up the microphone and hit record or start a file and the software does all the transcribing for them, with a less-than-80% accuracy rate. Believing they can replace court reporters with their imperfect speech recognition technology, and then just hire scopists and proofreaders, like reporters do, to polish it and complete it, they’ve gone all in with years of R&D in the hopes of striking gold and being on the forefront of what they believe to be revolutionary technology.

What these ignorant money-grabbers fail to understand is that they are taking us backwards by about 60 years in time. ASR software is not ready for the big leagues of the legal industry. ASR has about a less-than-80% accuracy rate, not including punctuation. When court reporters hand a file to their scopists, the file is already 99.5% accurate including punctuation. The scopist spends about an hour for every 20-30 pages even with a 99.5% translation rate. For a scopist to do 20 pages in a Word document, without the hyper keys, on a transcript with an 80% translation rate, it would take quadruple the amount of time it takes a scopist that works with a skilled professional. They’re not making it more efficient; it’s the opposite. They’re taking a highly efficient system of creating a transcript and turning into a nightmare. Nobody in their right mind would take that work.

The big box agencies have been peddling their snake oil for years now, long enough to be awakened to their pyramid-scheme-like collapse that is coming. Big boxes are sending emails to the court reporters they tried to replace behind their backs, begging them to help transcribe their growing mountain of recorded proceedings, asking them to refer their scopists, inviting them to enticing presentations only to pull a bait-and-switch on them asking for their help with accomplishing their mission to convert everyone to their new high-profit swindle.

In the following sections, we’ll explore the impact of this digital revolution on court reporting and the consequences it has for the profession and the legal industry as a whole.

The Digital Disruptors in Legal Transcription

The spiel from the outliers peddling their digital solution will tell you something like this:

It is not profound and it is not a revolution. Like I said, court reporters have been using digital audio recording for decades using the most efficient method, a steno machine and CAT software, to make transcripts. What is revolutionary is that the agencies are wanting to oust court reporters, take the 50-70% of the profit for themselves, replace them with unskilled workers they are recruiting “off the street,” and taking over our responsibility as the Responsible Charge who oversee the chain of custody from beginning to end. That is the revolution that is happening. It is profoundly greedy and bold! It is also against the law in 28 states that require certification. It is all about money and profits, and cares nothing about the integrity of the record.

Their marketing brochures and websites also describe it like this:

“Specialized audio recording equipment” is nothing better than the recording equipment that court reporters have been using and investing in for decades. Professional Court Reporters spend $800 on the Martel Electronics, high-gain microphones that are wireless and used for sidebar conferences, the $300 USB high-gain microphone that reduces ambient noise and you can hear a pin drop, and the $400 noise-canceling headphones. The one thing that reporters don’t do, and don’t do it for a reason, is mic up everybody in the room and create an 8-track recording where you can turn up one speaker’s recording and lower another’s so that a transcriber could get all the speakers who are talking at once. It may seem like a dream to an anal-retentive, obsessive compulsive transcriber, but that’s not how to make an accurate transcript. Proceedings should be heard by everyone in the room, and the reporter is there to make a record of what happened in the room and control the conversations so that everything is taking place one at a time where everyone can be heard. A judge can’t be expected to make a decision on something if they weren’t able to hear what is being said because an eruption of cross-talk, yet to a court of appeal reading it later, it would look like the judge were able to hear and understand all speakers clearly if the speakers were all mic’d up and had their own separate tracks that could be transcribed clearly. Court reporters, as the responsible charge, are the witnesses to what happened live in that room, and the record will be as close to what the judge heard at the time, which is why court reporter sits the closest to the judge and the witness. We should not be creating a record of two proceedings that are taking place, one that can be heard by everyone, and one that can be heard on playback with volume lowering and raising controls or whispers that no one in the room could hear.

A professional court reporter in the room is able to stop the cross-talk and ask for repeats and request that they speak one at a time to make a good record. In a courtroom, if there is cross-talk happening, the judge and jury aren’t hearing everything that all the speakers are hearing. Most likely, they are hearing the loudest speaker. Official reporters usually focus on and writes what the judge says when there are multiple speakers and are unsuccessful in attempts to interrupt. The Court Reporters Board has punished reporters who fill in transcripts from the audio recording that they did not take down stenographically on their machine.

If a judge and jury couldn’t hear it, then why would someone create a transcript that would appear to the appellate court as though it was a conversation that everyone could hear, instead of all mayhem breaking out. It’s the judge and attorney’s obligation to make the record, but they often neglect to say something that would make it clear in the record that a verbal fight just broke out and voices were raised and there were multiple speakers. On appeal, it would look like a conversation where everybody was heard with equal opportunity to be heard, and heard by all in the courtroom. The same goes for whispers, if the court reporter, judge, and jury didn’t hear an under-the breath snide remark, then it shouldn’t go in the record. Another reporter was punished by the CRB for adding in an “F” bomb from the videographers audio that the reporter didn’t hear at the time, but was told to put it in the transcript by one of the attorneys that would benefit from having it in the transcript.

These digital outliers entering the legal services market have no idea how to make a record in legal proceedings. Their ignorance shows abundantly in their assertion that their simply recording proceedings is superior. That’s just not how it’s done!

Calling Digital Recording the “Digital Age” is laughable. Again, professional court reporters were one of the first to use computers in the early 80’s. Court reporters have been doing remote proceedings for over two decades and taught the entire nation of attorneys how to do remote depos using Zoom and other remote platforms. And court reporters have been using digital audio recording equipment for decades. It is not a “significant enhancement.” It’s actually a step backwards by about 40 years.

The “advanced software” and “algorithms” they’re talking about is Speech-to-Text recognition software. And it does not transcribe audio recordings efficiently. Have you ever used Siri or Alexa? Then you’ll know how inefficient it is. How many times have I yelled at Alexa to turn the air conditioning on, only to end up having to walk over and do it manually. Yeah, it’s like that. It’s inaccurate. An 80% translation rate in court reporting is abysmal. It’s like sending a student at 160 words per minute into a deposition where everyone is talking at 300 words per minute. Their translation rate will be probably better than 80% that ASR can accomplish. It actually SLOWS down the transcription process.

When reporters are requested to produce a transcript that has been videotaped, they usually charge more. Why? Because now they have to listen to the entire audio when they are scoping and editing their transcript to be sure they have every “okay,” “and,” “all right,” “uh-huh,” perfectly. It takes LONGER when you have to compare what’s on their steno-created transcript to what they hear in their audio. And the ASR-generated transcript will take four to 8 times longer. It is less efficient. You will be able to produce half the amount of transcripts that a stenographer could do. If an agency is just sending digital recorders to record things, and everybody orders it and wants it expedited, guess what? You’re probably going to be waiting a long time to get your transcript with the backlog and the inefficiency.

This “cost-effective” spiel is another lie that digital outliers are propagating. One would think that replacing a highly-skilled reporter with one they can “pull off the street” making minimum wage would cut costs, but it doesn’t. Agencies are sending digital recorders and charging the attorneys the same fees that they would have charged had they sent a court reporter. And because it takes longer to produce a transcript using slower and inferior methods, it takes more people to create it, and even at minimum wage, it’s going to cost more. And because agencies are commoditizing it and offering lower and lower rates, they can’t even use Americans to do the work. They have to send the transcribing work out of the country to the Philippines or Africa to get rates cheap enough. But the truth is, the agencies are motivated to keep more of the profits for themselves by cutting out the largest cost in the chain, the stenographer. A stenographers’ cut consists of anywhere from 50% to 70% of the job. The large agencies are backed by private equity companies and investors who have advised them to cut the largest cost in order to reap more profits for the shareholders. Agencies are not passing the savings on to the attorneys; they’re keeping the invoices exactly the same and pocketing the profits.

Professional court reporters and their agencies are already digitally storing their transcripts and audio recordings that are easily uploaded, stored, shared, and retrieved electronically by courts and attorneys. Nothing new or revolutionary here. There’s no issue with accessibility in the existing model. For the past two decades, court reporters have been technologically savvy enough to do all of this. A huge advantage with court reporters doing this is that a decentralized model provides for the highest security and protection of the record. A reporter has up to 7 back-up methods for the transcript, and then they send it to the agency, which has their own repository, and uploads their steno notes directly with the court, where they have their archive for all the transcripts. When you go with one of these digital companies, you’ve got ONE server storing all the transcripts. And the revolving door of the digital recorders they hire would make it impossible to find them if the digital company lost the file.

Professional court reporters already do this and have been doing it for decades. Next.

To be clear, the demand for stenographers is stronger than ever, and according the the US Bureau of Labor Statistics will grow by 3% by 2032. There are a lot of agencies who are offering digital solutions, out of a pure profit motive, but most local court reporting agencies are sticking with a strictly stenographic service model. There are a ton of outlier companies that have popped up with no background, knowledge, or experience in this industry and who don’t even know the lingo. It’s like the wild wild West or the Gold Rush where everyone is seeing green, wants to get in, make their millions, and then exit as fast as they can.

Professional Court Reporters find themselves victims of the corporate greed of their largest industry allies – their large agencies and vendors – manufacturers of their machines and CAT software. They are also in jeopardy of the judges and attorneys who are being marketed to by these irresponsible outliers and propositioned to buy their snake oil and replace us by recording equipment. It’s one of the biggest scams. It’s the biggest fraud to ever hit the legal community. It’s a bigger fraud than Elizabeth Holmes who defrauded investors of $700 million by claiming to have revolutionized blood testing. When the truth finally comes out, it will be noted as one of the Biggest Disappointments of the 21st Century!

In the following section, we will dispel myths and delve into the disadvantages of using digital audio recording and transcription services, shedding light on the reasons behind the growing unpopularity of these as viable solutions in the legal world.

The traditional method of court reporting has just as much long-term viability as it always has. In the 1980’s, court reporters entering school were told that they would be replaced by machines. Those reporters are now in their 44th year of reporting. In 1993, Los Angeles Superior Court tried to record proceedings, against the law, and the California Court Reporters Association sued the court and won. It was appealed, then cross appealed, and the court reporters were victorious in the end.

Digital solutions do not present a cost savings to attorneys. The court reporting agencies who are sending digital reporters are invoicing the attorneys the exact same fees as they would had they sent a traditional stenographer. What they may save in sending an untrained person to record the proceedings, they’re having to pay more on the back end with transcription services, scoping, proofreading, and the ASR software they’re using to create an inferior product. Courts are having to spend millions of dollars on audio equipment. The stenographers’ maintenance of their specialized equipment is built into their fees and is a cost of their doing business.

Court reporter rates have not increased since the 1980’s. In fact, in a lot of cases, their fees have dipped below what they were charging in the 1980’s. Court reporters haven’t had a rate increase in over 50 years. In 1970, the statutory page rate in California was $3.00/pg. In 2021, that statutory page rate was still $3.00/pg. If you plug that $3.00/pg figure into an inflation wage calculator, that $3.00/pg from 1970 should be $18.00/pg in 2024.

Traditional court reporters have enjoyed enhanced accessibility of their transcripts for decades. Court Reporters have been uploading their transcripts to the court system for two decades and they’ve been uploading them to agency archives for over three decades. They’re easily stored, shared, and retrieved electronically. This is not a differentiator.

The real-time transcription that is captured by Automatic Speech Recognition software is only about 80% accurate and is not ready for the legal industry. It’s almost completely unusable.

There is absolutely no improvement in searchability between a digitally created transcript and a traditional court-reporter-created transcript. Court reporters’ transcripts have been searchable for at least three decades.

The term “corporate cannibalism” refers to the phenomenon where established entities within an industry adopt and promote innovative, often digital, solutions that ultimately render their own traditional services redundant. This trend is particularly evident in the court reporting industry as it transitions from human court reporters to digital audio recording and transcription services.

The introduction of digital audio recording and transcription services is, in essence, an example of corporate cannibalism. Companies within the legal tech sector have realized the potential cost savings and efficiency gains associated with digital solutions and have actively promoted these alternatives. While it is a rational response to changing technological landscapes, this shift has significant consequences.

1. Job Displacement: Perhaps the most immediate and visible impact of this corporate cannibalism is job displacement. Human court reporters, who have been central to the legal process for generations, are finding their roles challenged. As digital imposters gain prominence, the demand for stenographers and court reporters decreases, leading to potential job losses and industry disruption. Veritext has allegedly given a national corporate edict to all its offices to ensure that 50% of its business is sending digital recorders. Court reporters all over the country are complaining on Facebook that their job was canceled and the agency sent a digital recorder instead, and that there is less work now than ever in their careers.

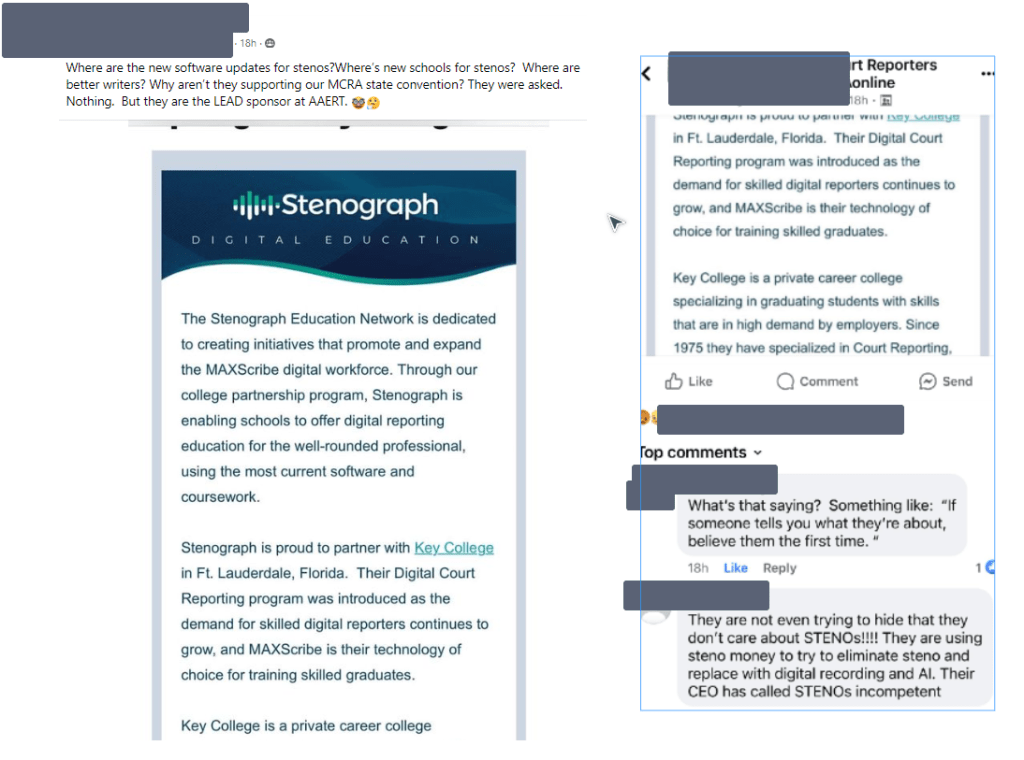

2. Implications for the Industry: The transition from traditional court reporting to digital solutions raises questions about the long-term implications for the industry. Will it be possible to maintain the same standards of accuracy and reliability with digital transcription? What impact will this shift have on the legal record’s integrity and trustworthiness? I can assure you that a decline in the work that traditional court reporters are getting because they are being replaced by digital recorders could lead to an abrupt extinction of traditional court reporters. The vendors will stop servicing their CAT software and machines, stop producing new machines, stop developing new advanced features. Court reporters are complaining that Stenograph, the industry’s largest supplier of CAT software and steno machines, has already stopped rolling out new features and customer service response times are suffering.

3. Legal and Ethical Concerns: The shift to digital solutions also raises legal and ethical concerns. Privacy, data security, and the potential for errors in transcripts are pressing issues. The legal profession must navigate these challenges and establish regulatory guidelines for the digital transcription industry to ensure that standards are maintained. It’s my opinion that unless you have a licensed individual acting as the responsible charge of the record, it will be impossible to ensure an accurate record that is secure.

4. Market Disruption: The adoption of digital solutions has caused significant market disruption. Long-standing court reporting firms have had to adapt to this changing landscape. Some have successfully integrated digital transcription services into their offerings, while others have faced challenges in doing so.

Corporate cannibalism in the court reporting industry reflects the broader trend of digital disruption in many sectors. The legal industry is grappling with a fundamental transformation, and it’s crucial to strike a balance between leveraging the benefits of digital technology and preserving the quality, accuracy, and ethical standards of legal documents.

In the following sections, we will delve deeper into the legal and ethical challenges posed by the digital shift in court reporting and consider the potential future of this evolving industry.

Legal and Ethical Challenges

The digital transformation of the court reporting industry brings with it a host of legal and ethical challenges that require careful consideration.

1. Privacy Concerns: In a legal environment, privacy is paramount. The use of digital audio recording and transcription services raises concerns about the security and confidentiality of recorded legal proceedings. Access to sensitive information must be strictly controlled to prevent breaches and ensure that the privacy of those involved is maintained.

2. Data Security: Legal transcripts often contain sensitive information. Digital storage and transmission of this data make it vulnerable to cyber threats. Ensuring robust data security measures, including encryption and secure storage, is imperative to protect the integrity of the legal record and prevent unauthorized access.

3. Transcript Accuracy: While digital transcription services are efficient, they are not immune to errors. Ensuring the accuracy of transcripts is a legal and ethical imperative. Legal professionals must have confidence in the veracity of the records they rely on for case preparation and decision-making. Human oversight and quality control are crucial to achieving this.

4. Admissibility in Court: Legal professionals must grapple with the admissibility of digitally transcribed records in court. The acceptance of digital transcripts as official records varies across jurisdictions. Legal standards must adapt to recognize the authenticity and integrity of digital records.

5. Ethical Considerations: Legal ethics are a cornerstone of the profession. Transcriptionists must adhere to ethical standards, ensuring impartiality, accuracy, and the protection of attorney-client privilege. The use of automated transcription technology also raises questions about transparency in disclosure of the use of such tools.

6. Accountability: In the event of errors or disputes, accountability becomes a challenge. Determining responsibility for transcription errors or data breaches can be complex in a digital environment. Clear protocols for accountability and dispute resolution are essential.

Navigating these legal and ethical challenges is crucial to ensuring the continued integrity of the legal record. The legal profession must evolve its practices and standards to accommodate the digital age while upholding the principles of privacy, accuracy, and accountability.

In the subsequent sections, we will examine real-world case studies that shed light on the impact of the digital shift on the American Judicial system and the potential consequences of the widespread adoption of digital transcription services.

Pushed to the Brink of Destruction

An interesting case study of product cannibalism is in the beverage industry. Diet Coke’s sister brand, Coke Zero Sugar, is pushing Diet Coke to the brink of destruction. In August, 2023, Coca-Cola stopped selling Coke Zero in the US, replacing it with a beverage with a different recipe, design, and name: Coke Zero Sugar.

While people immediately freaked out when the change was announced, the adjustments are already paying off. After the new recipe rolled out in the US, unit case volume doubled compared to the prior quarter.

Meanwhile, Diet Coke’s sales slump continues as the weakest link in the company’s cola lineup. The brand’s sales by volume declined in the mid single digits last quarter. And, executives said that Coke Zero Sugar’s success is cannibalizing Diet Coke and Coca-Cola Classic sales in certain markets.

Increasingly, Diet Coke doesn’t fit health-conscious customers’ needs. While Coke Zero Sugar saw a sales bump by very clearly advertising that it doesn’t contain sugar, many customers remain suspicious of Diet Coke’s use of artificial ingredients.

However, Coca-Cola is paralyzed from significantly altering Diet Coke, in the way it tweaked Coke Zero, due to its dedicated – albeit shrinking – fan base.

“I don’t think we’re likely to change Diet Coke,” CEO James Quincey said in a call with reporters Wednesday. “It has a large following.”

Sound familiar, court reporters? The only thing saving Diet Coke is their large, dedicated following, but shrinking. So if it shrinks enough, they’ll be able to kill Diet Coke altogether in the near future. “Don’t think” and “likely” doesn’t give me confidence in Diet Coke’s future. Quincey could have said, “We’re never changing Diet Coke!” But his statement is non-committal.

It reminds me of some of the exact statements by the CEO’s in the court reporting industry, promising reporters that court reporters will always have a job. Then they talk about retraining, which means they plan to move the highly-skilled stenographers into relegated tasks of signing their certs on transcripts that were produced by someone in Africa.

The one thing that hasn’t killed off court reporters yet is our dedicated, loyal fan base of judges and lawyers. Court reporters should cater to this fan base right now. Court reporters are so busy recruiting new court reporters because of the fraudulent shortage propaganda that they’re not out there getting in front of the judges and attorneys trying to show and impart their value to them in meaningful ways, off the record.

Court reporting schools are overflowing, and soon there will be a glut of reporters like the industry saw in the 1980’s, which will lead to further stagnant rates, if not declining, for the highly-skilled tradesmen. Not only are agencies proliferating this over-inflated shortage narrative, but they’re inflating the prices they’re charging for court reporting services, even though they’re negotiating down the already 50-year-old rates to reporters. It’s a one-two punch to the industry. The agencies are pitting the attorneys and judges, our loyal fan base, against court reporters and the attorneys are mad as hell as they’ve pushed what the market will bear to the breaking point.

Market cannibalization is generally disadvantageous to a company. It does not provide any increased profits. Instead, it leads to a decrease in revenues, translating to a future decline in earnings. Market cannibalization creates competition within a company’s own products in the market. Due to this, the company suffers from a decreased market share.

However, in this case, in the court reporting industry, it’s highly advantageous to companies (court reporting agencies) to embrace digital recording, because it does provide increase profits, to the tune of 50% more profits. That’s huge. And it’s not resulting in decreased market share at all. They’re just shifting their existing customers to the new way of doing things and training them well.

In the case of Stenograph and other manufacturers of CAT and steno machine products, it’s about mitigating the diminishing numbers if they believe the fraudulent shortage narrative. It allows them to capture a market outside of their base of legacy court reporters. If they can “recruit anyone off the street,” as Anir Dutta, CEO of Stenograph has been shown in videos to say, then it allows them to capture new sales of their new product, MaxScribe, and open up a new market. Dutta, by the way, has also held a seat as the president of the STTI, Speech to Text Institute, which created the fraudulent marketing materials showing an overinflated shortage prediction that is not based on fact. Dutta, also, by the way, helped Kodak get rid of their physical film product and go all digital, during his time as a sales representative for Kodak.

No wonder Silicon Valley investors are all abuzz right now over their court reporting investments. This product cannibalization boon is probably like nothing any of these SV investors have ever seen before in any other industry – technology, food, beverages. Usually, you’re losing revenues and marketshare when you introduce a competing product. But not in court reporting.

With the one-two punch strategy of promoting a false shortage narrative and then inflating prices, these big box court reporting agencies are able to easily sell their new solution to overcome the “shortage crisis” and help curb the overinflated pricing court reporters are charging. They’re the savior of their own manufactured crisis! Brilliant!

How To Avoid Cannibalization in Court Reporting

The good news for court reporters is (1), that legacy court reporters have an undying fan base, and (2), that there is a way to combat cannibalization.

Enterprises usually invest significant financial and human resources when developing and launching a new product – and these costs should also be taken into account. They also incur expenditure when marketing and promoting it to the target audience. Factoring these costs into the calculations may show a negative impact on the bottom line. In the case of the court reporting industry, if the enterprises are gaining 50% profits, that’s a lot to help offset their efforts. It’s basically paying for itself. But for how long? Marketing to their existing customer base costs them very little extra with email blasts and using their existing outside sales reps and conducting trainings to attorneys. Marketing to attorneys outside of their customer base gets into the millions, so that becomes more expensive. However, their competitor big box agencies are also training their own existing customer base, which altogether could be about 50% market share.

The cost of recruiting and training digital court recorders is huge for the big boxes, especially when the turnover rate is exponential.

Then there’s the cost of legislation. This plan fails if they fail to get legislation passed in the 25 states that require certification of transcripts. They are trying, and failing, so far in CA with SB 662, and Illinois, and others. Yet, Veritext, US Legal, Planet Depos, and others, are hiring “Digital Court Reporters” in all states, even in CA, where that title enjoys title protection. They’re sent cease-and-desist letter by the CRB only to be caught violating that law again weeks later. The COO of Veritext pretty much shared that they are doing about $10 million in CA in digital recording business already, and that was years ago. Their plan, if they cannot get legislation passed, is to do it anyway, because, well, the “shortage crisis” and all. Then they can say, well, we’ve been doing it forever already and it’s working great. Kind of like how marijuana was so pervasive, even judges were smoking it, so why not just legalize it and decriminalize it.

Apple is a prime market cannibalization example. Every time a new iPhone is introduced, the price of older models falls on the market. For instance, when it announced the iPhone 11, 11 Pro and 11 Pro Max, it lowered the price of the iPhone 8 and XR by $150. It even had to discontinue the iPhone 7, iPhone 7 Plus, XS and XS max. Although the discontinued iPhones may still be available, people would have to buy them used or through unofficial channels, at much lower prices.

The effect of price cannibalization on older iPhones shows that companies need to be flexible and adaptable when it comes to new products. Not all companies can be like Apple and discontinue older models whenever they launch a new product. They need to be very careful about cannibalization on their product launches. Adaptability is key to the success of new product launches for businesses that already have an established presence in the market. This is the reason the big box court reporting agencies are keeping court reporter around, for now. They can’t just discontinue the older model vintage court reporter until their new digital imposter product has completely taken hold.

It is vital to confront cannibalization concerns head-on instead of getting needlessly defensive.

Take calculated risks, monitor the prices of competing products, factoring in price cannibalization, and be flexible to make changes on the go – that’s the secret to reaping long-term benefits.

Also, leverage existing customers and up-sell new products in a way that is in line with the business goals.

- Take Calculated Risks. What are some risks court reporters could take? Hmmm, scratching head emoji. There’s one that comes to mind that reporters have been saying on Facebook for years. Stop working for the big box agencies who are cannibalizing their legacy court reporters. Stop buying CAT software and Writers from companies who are cannibalizing their legacy court reporters. What could a move like this do? It would cut into their existing market share immediately. These enterprises are counting on not having any affect on their market share in order to pay for the costs of launching their new product. If reporters were to cut off the funds that the BB agencies are using to launch their digital alternative product, then they won’t have money for legislation, marketing, training, etc. These enterprises are counting on having 50% of their business come from legacy reporters. What if their base of legacy reporters were to suddenly disappear unexpectedly? Then they would lose that 50% that they’re expecting to continue forward with their plan. It’s different than a physical product like Apple’s where Apple actually owns the product being discontinued and can control the pricing and availability of their own product. The big box agencies don’t own court reporters, who are independent contractors, yet they are calculating their risks as if court reporters working for them are a sure thing. So far, the big box agencies’ base of loyal independent contractors are keeping their plan in motion for them, unwittingly at the demise of the legacy IC’s. What if… this is a real possibility here. If their legacy court reporters were to stop working for them right now, like right this very second, and 50% of their traditional business were to suddenly go away unexpectedly (Right? because they were counting on that 50% being there so they could still be known as a “court reporting” company), then what would happen to their plan to cannibalize legacy court reporters? If that were to happen and court reporters were willing to take a big risk in order to stop this proliferation of digital court recording, I promise you, the Big Box agencies would become just “Transcription Companies” and would no longer be able to call themselves a court reporting agency. Court reporters could cast them out of the court reporting industry altogether and leave them to their newly created niche industry and easily differentiate their services. This could put court reporters at a huge advantage in being able to fight against it. I just laid out how cannibalization works. I just showed you how they need their legacy reporters to stay in business and fund their evil plan. Do reporters, after reading this article, still want to work for them?

- Pricing. Court reporters could start keeping a database of the rates the agencies are billing attorneys and what they’re charging for digital services. Start asking attorneys for invoices, start researching public court documents for “motions to tax costs” sections of the court database, find out everything you can about costs in your market. What are other reporters charging – to agencies and to attorneys. Having pricing transparency is a tactic used in states like Texas. Legislating pricing transparency, forcing agencies to publish their pricing and share invoices with court reporters and court reporters’ fees also being transparent so attorneys and judges can see the real numbers would a very effective strategy. It would also destroy the myth that digital court recorders are cost effective. Legislating full disclosure about using digitals isn’t a bad idea while we’re on the legislating topic.

- Leverage Fan Base. Court reporters must keep their fans loyal by continually reminding them of their value. Court reporters should be attending bar association meetings, publishing articles in law publications, visiting law schools and giving classes on making a record to law students, speaking at bar association meetings and judicial counsel meetings and anywhere judges attend. Court reporters must be seen and heard and accessible to their fans, the end users of their products, the ones who will keep legacy court reporters working in the profession forever.

- Channel Dominance. Court reporters must look to the transportation revolution of the 1800’s for examples of gaining advantage. National parks, such as Mount Rushmore, that built roads to it, enjoyed the tourism revenues that helped sustain the local economy. Court reporters could build their own road. Dominate it. Get off the current distribution channel controlled by those with an agenda to cannibalize their legacy court reporters. A road such as this has been built for court reporters; it’s time court reporters take it for a drive and demand that everyone use that road alone to access their services. If court reporters can control and own their own road, they can control their own fate.

- Cut your losses and walk away. Some reporters enjoy seniority from the years working for one big box agency, so walking away from their agency is understandably not a welcome option. Also, court reporters have paid over $5k for their CAT software and $7k for their steno writer and then hundreds of dollars a year for their maintenance & support contracts are also understandably not easy to part ways with. So in a lifetime of reporting, their investment and training and decades of working with one CAT software vendor and steno machine vendor, their all-in investment can be valued at over $20k. It’s understandable that walking away from that kind of investment and starting over learning a new software and having to buy a new machine just to save the court reporting profession is a risky thing to do, especially when you can’t count on all the other court reporters to do the same thing. I mean, why be the only idiot taking all the risk and now you’re left with no seniority and having to fork over tons of money for new equipment, when nobody else walked away with you. And, not to mention the fact that most reporters work 48 years in this profession and as of 2014, the average age of reporters was over 56 years old. Many reporters are just hanging on, status quo, until retirement, rather than taking a risk at this stage in their lives and career. But strategy number 5, cutting your losses and walking away from these companies is a very powerful strategy to combat cannibalism. You are faced with being out of a career in the short future, so what do you have to lose? If the reporters that are left in the industry, without these above examples of those that probably won’t take the risk, can be a sufficient size in number, even 10% of the population of court reporters, then it could make a significant impact on stopping these cannibalizers.

The Future of Court Reporting

The future of court reporting stands at a crossroads, marked by the collision of tradition and the emergence of radical corporate greed. As digital audio recording and transcription services gain prominence, the landscape of the court reporting industry is evolving rapidly. The path ahead presents a series of potential scenarios and questions.

1. The Coexistence of Human and Digital Transcription: One possible future is the coexistence of human court reporters and digital transcription services. While digital solutions offer speed and cost-effectiveness, human transcriptionists provide expertise, context, and quality assurance. In this scenario, the legal profession may strike a balance that leverages the strengths of both approaches.

In my humble opinion, the ONLY solution where coexistence is possible is with Advantage Software’s CAT Software Eclipse, using their new Boost feature. They are the only CAT software company that is actually making it possible for ASR and traditional stenographers to coexist.

2. Legal and Ethical Standards: Legal and ethical standards in the court reporting industry will likely adapt to accommodate digital technology. This includes establishing guidelines for the admissibility of digital transcripts, data security protocols, and ethical standards for transcriptionists using automated tools. There is proposed legislation in CA with SB 662 to pass legislation that allows digital recording in all civil courtrooms, but it’s been repeatedly defeated. But legalizing digital audio recording and digital technology cannot happen in its current state, where ASR software tools do not have good enough translation rates to be used without a traditional human stenographer. Again, the only possible solution is to have stenographers use Eclipse with the Boost feature. We must continue to uphold laws that prohibit digital transcripts that are created by uncertified, unprofessional, unskilled, and unaccountable workers.

3. Technological Advancements: The future may bring continued advancements in transcription technology, including improved accuracy and real-time capabilities. These advancements could further enhance the efficiency of legal proceedings and the accessibility of legal records.

The future is here now. Again, Advantage Software has been working for the past five years at advancements in their CAT software, Eclipse Boost, that improves real-time capabilities of all reporters. These enhancements do improve the efficiency of transcript production and real-time feed accuracy.

4. Job Displacement and Reskilling: The court reporting profession may undergo significant shifts, with some job displacement but also opportunities for reskilling. The Big Box Agencies and Stenograph may want stenographers and court reporters to make the transition to roles that involve overseeing or quality-checking automated transcription processes, but that will never happen. Traditional stenographers would rather walk away from the career than be relegated to button pushers.

5. The Role of Legal Professionals: Legal professionals, including attorneys and judges, will need to adapt to the digital age, familiarizing themselves with digital transcripts and the tools used in the transcription process. Training and education may become vital components of legal practice.

My advice to attorneys, judges, and paralegals, fight against digitalization with every ounce of courage you can muster. Insist that only human stenographers report your proceedings. Insist that your transcripts are produced by professional, certified shorthand reporters. Do not accept digital transcripts as evidence. Digitally recorded proceedings with outsourced transcription to unskilled, low-wage workers is creating a slave workforce.

6. Technological Integration: Court reporting firms that give in to the changing landscape and incorporate digital transcription services into their offerings are being met by resistance of their traditional human resources. This integration may require partnerships with technology providers and investments in software and infrastructure. The future of court reporting is likely to be shaped by a delicate interplay between technology and tradition. The legal industry must navigate the complexities of privacy, data security, and accountability while preserving the quality and integrity of legal records. The coming years will test the adaptability and resilience of the court reporting profession as it continues to serve the legal needs of society in the digital age. There will be a great divide coming in the court reporting profession between agencies who adopted to digital button pushers and those who remained faithful to their human assets. Longstanding court reporting agencies will become “Transcription” companies, unable to recruit human shorthand reporters.

Case Studies

Examining real-world case studies provides valuable insights into the impact of the digital shift on the American Judicial system and the court reporting industry. Here are a few illustrative examples:

1. The Digital Transition of California Courts: The California court system has undergone a significant transformation by embracing digital audio recording and transcription services. This transition allegedly has led to increased accessibility of legal records and a reduction in costs. However, it has also raised concerns about the quality and accuracy of transcripts, as well as data security and privacy. In civil proceedings, the courts don’t pay for the court reporters, saving tens of millions, but then they purchase millions of dollars worth of recording equipment and servers to hold all the audio files, and the IT staff to maintain it.

The courts in California are breaking the law by electronically recording felony and civil matters. SB 662 was proposed and backed by the Judicial Counsel and judges all over California, yet it never got off the assembly floor, yet judges in LA County are not deterred from electronically recording civil proceedings.

2. The Role of Human Transcriptionists in High-Profile Cases: In high-profile cases, human transcriptionists have played a pivotal role in ensuring the accuracy and reliability of transcripts. Their contextual understanding and linguistic expertise are particularly critical in cases with complex legal terminology and nuances.

In the Alex Murdaugh murder trial in 2023, Circuit Court Judge Clifton B. Newman and Defense Attorney Dick Harpootlian discuss “how bad” the rough draft provided of the record by a digital firm was, calling it a “deficit product.”

3. Challenges in Rural Jurisdictions: In rural jurisdictions with limited access to advanced technology and skilled transcriptionists, the adoption of digital solutions presents unique challenges. Ensuring equal access to legal records and maintaining the quality of transcripts in these areas is a matter of concern. In the aftermath of Covid, court reporters have been appearing remotely and covering court and depo proceedings with relative ease all over the country.

These case studies exemplify the complexities and nuances of the digital transition in court reporting. They highlight the advantages and challenges faced by different jurisdictions and the evolving role of human transcriptionists in high-stakes legal cases.

Conclusion

The court reporting industry is undergoing a profound transformation, driven by greed. The corporate cannibalism of traditional services by digital audio recording and transcription solutions is a threat to justice in the legal industry. This shift has brought with it a wave of change with challenges that demand careful consideration.

The lack of advantages of digital audio recording and transcription services are evident, including a non-existent cost savings, bogus claim of enhanced accessibility, and real-time capabilities that are a “deficit product.” The only benefit that has made digital solutions increasingly attractive to agencies is the immediate gain of 70% profit margins. The shift to digital transcription is fraught with legal and ethical concerns about privacy, data security, and transcript accuracy. Job displacement in the court reporting profession raises questions about the industry’s future.

Real-world case studies have illuminated the impact of the digital shift on the American Judicial system and the court reporting industry. These cases demonstrate the complexities of implementing digital solutions in diverse legal environments.

As the future unfolds, it presents a spectrum of possibilities, including the coexistence of human and digital transcription, adaptations to legal and ethical standards, and continued technological advancements. The role of legal professionals, industry practices, and the resilience of the court reporting profession will all shape the way forward.

In this dynamic landscape, the court reporting industry faces a dual challenge: fighting the advancement of digital technology while keeping the number of human stenographers growing. Finding the delicate balance between tradition and innovation is essential as the legal profession navigates the road ahead.

As we conclude our exploration of corporate cannibalism in the court reporting industry, we leave the future of court reporting to be shaped by the ongoing interplay of technology, tradition, and the unwavering commitment to the principles of accuracy, integrity, and privacy.